751008 - Conversation - Durban

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

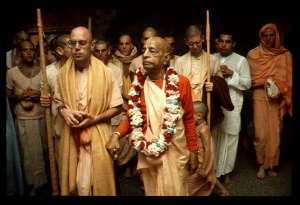

(Conversation with the Rector, Professor Olivier and Professors of the University of Durban, Westville)

Professor: . . . this morning from the east and from the west. Unfortunately, the rector is busy . . . the principal is busy this morning with somebody in his office, but he will be here just now. So we may just as well, shall I say, introduce. Perhaps I should say something about the university.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Yes.

Professor: Now, I just want to say as far as the . . . I don't think it's necessary for me to sketch the background history of the Indian community of . . . (break)

Prabhupāda: You have given description. May I ask you one question? The transmigration of the soul, do you take it as science or religion?

Professor: Yes. Here we take it as religion.

Prabhupāda: Then what is your definition of religion?

Professor: My definition of religion is ultimate . . . that which has to do with your ultimate concern. Ultimate concern. I mean, I can make religion out of . . . if my ultimate concern is money, then that is my religion, to put it that way. Or ideology and so forth. But it is my ultimate concern, what is my ultimate concern in life. What is my ultimate concern. Every man is religious. He's a homo religiosus, to put it in Latin. He's a religious being. Just as he wants to eat, he has to have religion.

Prabhupāda: So the transmigration of the soul, you take it as religion. It is not a science.

Professor: We haven't progressed so far.

Prabhupāda: But so far we are concerned, that is basic principle of our further investigation in religion.

Professor: Yes.

Prabhupāda: We are preaching Kṛṣṇa consciousness. That is on the basis of Bhagavad-gītā. So the beginning of Bhagavad-gītā is the teaching of transmigration of the soul. Dehino 'smin yathā dehe kaumāraṁ yauvanaṁ jarā, tathā dehāntara-prāptiḥ (BG 2.13). So that is our first concern, dehāntara-prāptiḥ. This body will not exist, and we have to accept another body. Kṛṣṇa says, dehāntara-prāptiḥ, "another body." Now, there are 8,400,000 different types of body. Which body I am going to accept, there is no education. So I am kept in darkness. So what is the value of my education?

Professor: You mean your future?

Prabhupāda: Yes. I do not know what is my future. Then what is my education?

Professor: Yes. Yes. Of course, that is one standpoint, isn't it?

Prabhupāda: No, that is the main standpoint. I am taking education in the university. I do not know what is my future. Then where is the education? I am in darkness.

Professor: Yes. But the main thing is, from the Hindu point of view, you have the opportunity . . .

Prabhupāda: It is not the Hindu point of view. It is science. Tathā dehāntara-prāptiḥ (BG 2.13)—that is applicable both for Hindu, Muslim, Christian, everyone. Just like a Hindu child and a Muslim child. Does it mean that Hindu child will not grow to become young man? Only the Muslim will grow? The dehāntara-prāptiḥ—a child becomes a boy—that is equally applicable to the Hindus, to the Muslim, to the Christian, to everyone.

Professor: Of course, yes.

Prabhupāda: Then where it is the religion? It is the science.

Professor: Yes. But the Christian, for example, says . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no. I say from practical . . . a Hindu child becomes a boy, and Christian child also becomes a boy. You cannot say that because you are Christian you will not become a boy. Can you say like that?

Professor: Oh, no.

Prabhupāda: Or because you are Christian you will not become an old man. Can you say like that?

Professor: I am following your argument, yes.

Prabhupāda: So it is the science. So if this science is not in your university, then you are in darkness.

Professor: Now, we teach it as religion, but whether you take it . . .

Prabhupāda: Again you say religion. It is not religion; it is science.

Professor: Fine. You say it is a science, I say it is religion.

Prabhupāda: Now, you have to say, because you also grow. You shall also grow old man like me, not that because you are Christian you will not grow old man like me.

Professor: In any case . . .

Prabhupāda: No, this is the first proposition, that if you keep people in darkness—he does not know what is his future—then what is the use of education and university?

Indian man (2): So do you mean that the university should be abolished?

Prabhupāda: Not abolished. But education means that you must know what is your position.

Indian man (2): With due respect, I want to know what is the line of demarcation between science and religion.

Prabhupāda: Science means which is applicable to everyone. Religion is described in the dictionary, "a kind of faith." Faith . . . I may be Hindu today; tomorrow I may be Christian. That is . . . I can change.

Indian man (2): But this is not the definition of true religion.

Prabhupāda: No, no. I am not talking of religion. I am talking of science. Religion is a kind of faith. You may be believe or you may not believe.

Indian man (2): No. There is no question of belief. The question is whether the . . . what is the difference between religion and science? If difference is known, then the learned person can make him right or wrong at that time. But unless and until the demarcation of line between religion and science . . .

Prabhupāda: Now . . . yes, that we can say like this, that "Two plus two equal to four," this is applicable to the Hindus, Muslim, Christian, everyone. This is science.

Professor: Yes. No, no, I understand. I understand. I know where your argument is going to. But any case, let us beg to differ. Because . . . let us accept it. I just want to say I agree with you in this sense. I agree with you in this sense, Swami, that if we do not pay attention to the religious side, then we keep the people in darkness. We have to, on the religious side too. (someone entering) Professor Olivier, the rector. (introducing) . . . and this is Swami Bhaktivedanta.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: The principal of the university, Śrīla Prabhupāda. Hare Kṛṣṇa. How are you?

Professor: And Mr . . . . (indistinct) . . . Singh from Pietermaritzburg, and Professor Maharaj you know. And all the other ladies and gentlemen . . . (indistinct)

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: (to Professor Olivier) Would you like to sit beside Śrīla Prabhupāda?

Prof. Olivier: Yes.

Prabhupāda: (to Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa) So you can explain what I was talking.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Yes. So the idea is that now you have secular state, because the religion as it is being taught today is being accepted simply, or seen simply as some kind of dogma that can't be proven, some kind of blind faith. But in the Bhagavad-gītā Kṛṣṇa is giving scientific evidence, reason, how the existence of the soul can be proven. Religion means there must be soul. But people, they don't understand how soul is existing. They think it is simply beyond their conception or comprehension. Kṛṣṇa has made it so reasonable to understand the existence of the soul that any sane man would accept. For example, Kṛṣṇa says, dehino 'smin yathā dehe kaumāraṁ yauvanaṁ jarā (BG 2.13). Any person can accept that they had a youthful body, childhood body, and then old man's body. The change of body is always there. Tathā dehāntara-prāptiḥ. And after this body we can reasonably accept that there is another body. Just as from childhood to youth there is change of body, from youth to old age there is change of body, similarly, old age, death, and then there is another change of body. But in all circumstances I am still the same person. My body is changed, but still I am experiencing that I am the same identity, the same person.

So this education is lacking in the universities because, generally speaking, all of the scientists in the universities, they are simply dealing with this body, simply dealing biology, physics, chemistry—simply with the body. So where is the question that this is not science? It is science. It is the science of the soul. When our spiritual master went to Massachusetts Institute of Technology—it is a very well known technological university—he questioned the faculty and students there that, "You are the most advanced technological university in the world. Where is that department that tries to understand the difference between a dead body and a living body?" So this is science. You can't say that it's not science. And it should be accepted as science by university professors and taught as such. Otherwise, if we simply turn our back on this philosophy . . . Kṛṣṇa says, rāja-vidyā: "This is the king of knowledge." This is not some sentimental proposition we are putting forward, but it is the king of knowledge, that the soul is existing, and after this body there will be another body.

So real education, therefore . . . just like you come to the university, you want to get a better job, not that you go to the university so that you can work an elevator when you come out. You go to the university to increase your standard of living, to have higher standard of living. So real education, similarly, is that you can have higher standard of existence in your next life, not that I come to the university and simply live like animal and then have to be demoted to the body of an animal in my next lifetime. Rather, the real education is how we can be elevated from this human existence to higher existence, or to spiritual, eternal existence. So the purpose of the science of Bhagavad-gītā is just this, that janma karma ca me divyam evaṁ yo vetti tattvataḥ (BG 4.9). If you understand God in truth, and fact, then tyaktvā dehaṁ punar janma naiti, you will never take birth again in this material world, but you will go back to the spiritual world, called Vaikuṇṭha in Sanskrit language. Vaikuṇṭha means the spiritual world, the place where there is no repetition of birth and death. Where there is no . . .

Prabhupāda: No anxiety. No anxiety.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: No anxiety. Yes.

Indian man (3): Excuse me, sir. We recognize six great religions of the world. Are you suggesting that the adherents of all the other religions of the world should accept as a science this doctrine of reincarnation or transmigration of soul? Are you suggesting that everyone, irrespective of the faith that they belong to, should accept the doctrine of reincarnation? Is that what you are suggesting?

Prabhupāda: (aside) You don't . . .

Indian man (4): Another question is . . .

Indian man (3): I want an answer, please. Are you suggesting that every person, whether he is Muslim or Christian or Buddhist or Jew or Parsi, or anybody else for that matter, should accept the Hindu doctrine of transmigration or reincarnation of soul in order that he may be called a really religious person or a scientific person?

Prabhupāda: Well, the difficulty is that we are talking of transmigration of the soul on scientific basis, but you are trying to give it a Hindu color. Why? To become . . . I have already explained. To become old man is equally applicable to the Hindus, Muslim, Christian. So why you say it is Hindu belief? It is not Hindu belief. It is a science. Why you are bringing "Hindu," "Muslim," "Christian"? I do not know why.

Indian man (4): The real question between this statement of Mr. Professor and you is that what is the religion and what is science. Unless the nature of science and religion defined . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. Science is applicable to everyone.

Indian man (3): But when you use reason for proving your . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. This is the reason, that a child is becoming boy, a boy is becoming a young man, a young man is becoming . . .

Indian man (3): Reason is the subject of logic, and logic is philosophy. So philosophy is the knowledge of generality, while the science is knowledge of particularity. Philosophy can be the subject of religion, but not the science can be the subject of religion. It is knowledge of particularity.

Prabhupāda: It is not religion. First of all forget religion. I am talking of science. That a boy is becoming young man and young man is becoming old man, this is science. What do you think, Principal? It is science or religion? Does it mean that only the Hindus become old men and the Christians do not?

Prof. Olivier: Now, my problem as a simple layman is how to make God relevant to the issues of the day. But since God's relevancy can only be related to the permanent, the problem becomes even more complicated. But I have to deal with practical situations. Everybody in a university . . .

Prabhupāda: This is practical situation, that . . .

Prof. Olivier: Yes, I would agree. It is one of the neglected avenues of learning that we have not been able scientifically, I think . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes, that is my point. That is my point.

Prof. Olivier: This is the point that he's trying to make, that we have not been able to absorb into scientific studies those spiritual components which go up to make the whole of man. And I would agree. I think it's one of the great shortcomings in our modern educational system, that we . . . not that we do not accept this. I think basically, as an infrastructure, we accept this. But it's like a house. When you look at all the superstructures you do not inquire too deeply about the foundations of that superstructure.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Thank you very much. (chuckles)

Prof. Olivier: And now your point is that the time has come for society and the world to find out if there are cracks in the superstructure—whether these cracks are just superficial cracks or whether they are caused by foundational cracks or shifts in the corners of the foundational structure. And I, like you, I believe that this is not entirely a question of . . . well, it's certainly not a question of whether, you know, it's Hinduism or Christian or Islam.

Prabhupāda: It is the foundation.

Prof. Olivier: It's the foundation. But we know so little about the foundation. When the rich man in the Bible asked the Lord to send this poor man down to warn his brothers, the Lord said they've had all the prophets all the years, and they haven't listened; any new evidence they will not accept either. I think that we have enough evidences around us. We need not seek more evidences, except, I believe, through more direct contact with the workings of the Holy Spirit itself, which I think is available. But again, which I agree with you, I don't think we have exploited enough—you could use that word advisedly—because the spirit is there. "It bloweth where it listeth." It is for us to get attuned to that spirit.

Another the point is, that we are concerned with: Who is going to do this? There has just been written a book in England, which I haven't read, and I hope to order it, but I've only seen the advertisement, namely, The Biology of God, which takes into consideration the points that you have raised here. Of course, there is . . . are a lot of objections to this book in principle. You know—how can a man try to biologize God, to give Him a physical, scientific being in terms of modern life? But I think in the last book in the Old Testament, Malachi, there is a, when the Lord was complaining about all these people who bring blind animals as a sacrifice or lame animals or weak animals, you know. The poorest in their flock they bring as sacrifices to the Lord. And He said, "It's not sacrifices that I want at all, if you bring this kind. It's obedience. It's truth. It's only truth that brings knowledge. It's truth that I want." But then He goes on to say you must . . . this is the challenge that you were referring to: how to . . . how do we open more windows from God or from the spirit of God onto this present world today? Of course, the good Lord is still God. And He uses . . . (break)

Professor: I include the transmigration of souls, and I include everything else, religion and the lot. But when I speak about science in the English language sense, the science in this sense, then I have a problem.

Prof. Olivier: Even the German word wissenschaft that we normally use, which covers, as you say, everything—this is not translatable. The word science is . . .

Prabhupāda: But in Sanskrit there are two words, jñāna and vijñāna. Jñāna means theoretical knowledge, and vijñāna means practical knowledge. So vijñāna is taken as science. Just like you . . . theoretically you know that two hydrogen-oxygen mixed together becomes water. And when you do it practically in the laboratory, that is science, vijñāna. So jñāna-vijñāna-sahitam. In the Bhāgavata it is said, jñānaṁ me paramaṁ guhyaṁ yad-vijñāna-samanvitaḥ. Knowledge of God should be practical application in life. That is vijñānam. And according to our philosophy, unless one has got perfect knowledge of his self-identification, he remains an animal.

Prof. Olivier: He is what?

Prabhupāda: He remains an animal. Just like a dog is thinking, "I am dog." So similarly, if I think, "I am Hindu," then what is the difference? Or if I am thinking, "I am this or that," with the bodily conception of life . . . yasyātma-buddhiḥ kuṇape tri-dhātuke (SB 10.84.13). If one is thinking in terms of bodily conception—"I am this body"—and based on this foundation, sva-dhī kalatrādiṣu bhauma-ijya-dhīḥ, our family, society, national, so many things we are building up on this bodily conception of life . . . so:

- yasyātma-buddhiḥ kuṇape tri-dhātuke

- sva-dhīḥ kalatrādiṣu bhauma-ijya-dhīḥ

- yat-tīrtha-buddhiḥ salile na karhicij

- janeṣv abhijñeṣu sa eva go-kharaḥ

- (SB 10.84.13)

Such person is no better than the cow and the asses, because he is giving his identification with this body, which he is not. And Vedic realization is ahaṁ brahmāsmi: "I am not this body, I am spirit soul." And the Bhagavad-gītā explains:

- brahma-bhūtaḥ prasannātmā

- na śocati na kāṅkṣati

- samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu

- mad-bhaktiṁ labhate parām

- (BG 18.54)

One, when he is on the platform of Brahman realization, then he becomes jubilant, prasannātmā, na śocati na kāṅkṣati. That life is required, Brahman realization. That is education.

Prof. Olivier: But, now, do you not think that Christianity and Islam accept this as well?

Prabhupāda: I do not say which religion accepts and which religion does not, but unless one understands that he is not this body—he is different from this body—his education is imperfect.

Indian man (2): But do I mean that up till now, Your Excellency were giving the question of transmigration, field of the science, and now you are also taking that subject of God in this sphere of science?

Prabhupāda: It is not God. God is far away. First of all I must know what I am. God is long, long distant.

Indian man (2): But what should be the . . .

Prabhupāda: First of all you understand what you are, whether you are this body or something other than the body. That is first.

Indian man (2): Whether we are different or separate from God, or we are God. (laughter)

Prabhupāda: That also dog can say: "I am also God." That is not very difficult thing.

Indian man (2): Whether God says or not, it is the question between us, whether we are God . . .

Prabhupāda: So, that bodily conception of life is dog-ism. Dog thinks "I am dog." Cat thinks "I am cat." Similarly, if I think "I am Hindu," "I am Christian," so what is the difference? Because you are giving some name of religion, therefore you are better than dog?

Indian man (2): With due respect, I want to know the God knows that He is God and dog knows he is dog?

Prabhupāda: Why do you bring God? I am not talking of God.

Indian man (2): Dog. Dog.

Prabhupāda: I am talking of the soul.

Indian man (2): Whether dog knows that he is dog?

Prabhupāda: Yes. He knows the body—"I am dog." That's all.

Indian man (2): Not about body. I am asking the question whether dog knows that he is dog, cow knows that she is cow?

Professor: Have they got the intelligence to know?

Prabhupāda: Unless he knows that, "I am dog," why he is barking? (laughter)

Indian man (2): Dog is barking, but does he possess discriminative knowledge?

Prabhupāda: That you do not know. Because you are not dog, you cannot understand what dog is thinking. You cannot say what dog is thinking. You cannot say what dog is thinking, because you are not dog. But you have to become dog, then how dog is thinking. For the present time, as you do not know what is dog . . .

Professor: If we don't start the lecture, we have the dog barking just outside. (laughter) So we have to go for the lecture at 11 o'clock, unfortunately.

Prabhupāda: What is that lecture?

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: The students have been invited to hear kīrtana and lecture, Prabhupāda, at another place.

Prabhupāda: Kīrtana?

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Yes.

Prof. Olivier: Might I just explain, I don't know whether we will have an audience. May I first of all say thank you very much for coming to the university. We are very honored also, sir, that you have been able to come, also that your guests have come, and that you have been able to come. Thank you very much for visiting the university. I unfortunately have a committee of my council meeting this afternoon, and the chairman is coming over shortly, so I will unfortunately not be able to attend your lecture. Thank you very much for coming. Some of you have been here before. We have this week a student break for a week before they start their examinations, so I do not know whether Professor Oosthuizen will have an audience at all. Maybe a few members of staff.

Professor: I told Mr. Bhoola when he asked me about the lecture, I told him that this would be a problem.

Prof. Olivier: Thank you very much for coming.

Prabhupāda: If there is no audience, what is the use of holding class?

Prof. Olivier: Well, Professor Oosthuizen here will take charge of you, but if there isn't an audience, I agree that one must be careful not to press too far. It may be more in the nature of a seminar. There might be people sitting around like this, and then there could be discussion. So that would depend on whether there is an audience. Students are funny people. They must be very strongly motivated before they will come away from their examination books at this time.

Prabhupāda: (aside:) So my time for taking bath is half past eleven. They can . . . you can stay. I can go.

Prof. Olivier: So thank you very much.

Indian man (5): I want to say, professor, that on behalf of the Ārya-paṭha-nīti-sabhā, I would like to request Professor Oosthuizen and to his department of Hindu Studies and Science of Religion to make it known to the students who are interested in the study of Hindu studies that at 21 Kalar Street we have this Vedic temple, and that the Vedic temple is open to all students who can see and also participate in this service.

Prof. Olivier: Thank you very much. Might I apropos of that just say here that we have here a department, Science of Religion. Then we have a department of Christian Theology. We have now started a department of Islamic Studies, which will concentrate more on the theological aspects as we go along. And then, if we can find the right guru, we can start a gurukula, a department of Hindu Studies or Hinduism. And Mr. Chotari and various other members of the local community here are assisting us to find the right spiritual leader. As far as Hindu studies are concerned, we give a course here in Sanskrit at the university.

Prabhupāda: You have seen our books?

Prof. Olivier: I got a copy of the Bhagavad-gītā at the last occassion when your representatives were here, which I thought was a very well brought out and a well-documented edition. The printing is also very good. So we are trying at this university to, slowly, to delve down into the infrastructure of education. Of course, one . . . in the Western society one has got to take cognizance of so many developments in the various fields of science. And the element of spiritual science certainly has been neglected. I would concede this point immediately. That is perhaps where this university can also still play a meaningful part. Of course, here we have representatives of three of the world's greatest religions: Islam, Hinduism and Christianity. And this will be part of Professor Oosthuizen's department, to try and take the best out of these and formulate for our students, and maybe for the rest of South Africa and the world that will listen, the essences of the religion that would really satisfy as we go along, and we . . .

Prabhupāda: We say that religion means the law given by God. So any religion must accept God. Then there is no difference. If . . . the law may be little different according to time, circumstances. But religion means dharmaṁ tu sākṣād bhagavat-praṇītam (SB 6.3.19). Religion means the law given by God. Just like law means the codes given by the state. That is law. Just like you are keeping, "Keep to the right" or "left" here. In America it is right. So somewhere, "Keep to the right," or somewhere, "Keep to the left," but because it is given by the state, it is law. Similarly, whatever law is given by God, that is religion. This is our definition of religion.

Professor: I think we have to leave slowly. Thank you very much.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Please won't you all take some prasādam?

Prof. Olivier: Thank you very much.

Prabhupāda: (to Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa) So I think I shall not be able to attend that class, because I take my bath at half past eleven.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: That's okay, Prabhupāda.

Prabhupāda: I will go. These people will remain.

Prof. Olivier: And you have your transport for you?

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Oh, yes. We'd like to show you some of the books and also . . . (break)

Prof. Olivier: . . . searching for truth. If it is not doing that, it is no longer science.

Prabhupāda: No longer science.

Prof. Olivier: I think this is your point. We have neglected the science of the spirit.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Prof. Olivier: And this is what we have to rediscover and work at.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That I want. Without science, simply sentiment will not help you.

Prof. Olivier: That's right. Sentimentality . . .

Prabhupāda: "I believe; you believe . . ." You may believe something, I may believe something, but everything should be on the scientific basis. That is wanted. So unless we understand this point that, "I am not this body, I am something else than the body."—there is no question of spiritual education.

Prof. Olivier: Correct. Then it becomes sentimentality.

Prabhupāda: Sentimentality.

Prof. Olivier: Love without honesty, without scientific honesty. Love without scientific honesty is sentimentality. Similarly, honesty without caring and love is cruelty.

Prabhupāda: (chuckles) Thank you very much. (end)

- 1975 - Conversations

- 1975 - Lectures and Conversations

- 1975 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- 1975-10 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- Conversations - Africa

- Conversations - Africa, S. Africa - Durban

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Africa

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Africa, S. Africa - Durban

- Conversations with Academics

- 1975 - New Audio - Released in May 2014

- Audio Files 30.01 to 45.00 Minutes