760610 - Interview B - Los Angeles

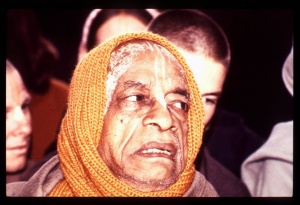

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

(Conversation and Interview with Richard from Coronet Magazine)

Prabhupāda: No, no. Curtain.

Rādhā-vallabha: Curtain, oh. Close?

Hari-śauri: Bring the shutter down. Shade, the shade.

Rāmeśvara: I showed Richard the "Hare Kṛṣṇa People" movie that Yadubara made, and Yamunā mātājī made some prasādam for him to taste. So he's gotten some introduction already.

Richard: Okay. You came here not too many years ago. Did you ever expect that it would grow into what it has over the years?

Prabhupāda: We came in 1965.

Richard: Eleven years ago. And in a relatively short period of time you've managed to gather around you a great number of people. Has it surprised you, or . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes, I did not expect. When I came here I did not expect, because we have got so many strictures, so I did not expect that here the people will accept my proposal.

Richard: Your proposal?

Prabhupāda: Yes. Because our proposal is "No sinful life." No illicit sex, no meat-eating, no gambling, no intoxicants. So I did not expect that anyone will accept this proposal. (laughs)

Richard: Are those three sort of proscriptions . . .

Rāmeśvara: Four.

Richard: Four, sorry. Are they prerequisites to accepting your knowledge?

Prabhupāda: The real thing is . . . you can easily understand that, "I am not this body, there is a living force within the body." Is it very difficult to understand? This body is not sufficient. The real body means the living force within the body. Is it not? You are talking—what is the difference, you're not talking? Now, if the body is dead, you cannot talk anymore. Finished. So what is that force within you that is causing you to talk? Do you know anything about that?

Richard: Have I thought about it? Me, personally?

Prabhupāda: No. Have you ever thought about it?

Richard: Yes.

Prabhupāda: So what is that?

Richard: What did I think about that?

Rāmeśvara: Yes.

Richard: Um, that I . . . I've always viewed myself as my self.

Prabhupāda: "Myself," that's what . . . you are not this body. You are not . . . body is not yourself. Did you ever think of it?

Richard: Well, when I say "myself," I should perhaps define it. "Myself" being all that I can recall being before, as well as my present, ah . . .

Prabhupāda: How do you distinguish between a dead man or living man?

Richard: Um, well . . .

Prabhupāda: The living man is important, but the dead man is not important.

Richard: Not his physical body, no.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Then within the physical body, there is something which is making him living man. Is it not?

Richard: Um . . .

Prabhupāda: What is the dead man? Something is missing; therefore it is dead. Otherwise the body is there.

Richard: Right. Okay. His ability to, to . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. Body is . . . the same hands, legs, mouth, eyes, ears, hair—everything is there, but now they're crying, "Oh, Mr. Such-and-such gone, oh, finished." What is that finished?

Richard: Well, his ability to share . . .

Prabhupāda: What is that ability? That is my question. Why this important man is now useless, although the same hands, legs, mouth, everything is there, but it is useless?

Richard: Well, he's no longer . . .

Prabhupāda: So what was the important thing?

Richard: The important thing was his ability to share physically and intellectually.

Prabhupāda: Yes, that means that important thing was within the body; now it is missing. That is distinction between dead man and living man.

Richard: As far as I'm concerned, that's it.

Prabhupāda: That is very important thing. This nice body can work on account of presence of that important thing. Otherwise, useless.

Richard: Right.

Prabhupāda: So we are preaching about that important thing.

Richard: Isn't that the object of all philosophies, both personal and . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. That is the real philosophy. You must take care of the living force within the body.

Richard: Right, and aren't there many ways that you can do that? Aren't there many approaches . . .?

Prabhupāda: First of all, let us understand the importance of that living force. Then we shall find out means how to keep it fit. But people are not aware of this living force. They accept this dead body as important. That is material civilization. They are taking care of the body but not the living force which is making this body important.

Richard: And you think that is a problem with . . .?

Prabhupāda: That is wanted. Education means to understand that, what is the important thing within this body. Otherwise, cats and dogs, they are also working with the bodily concept of life. The dog is jumping, barking. He's thinking, "I'm dog. I'm this body."

Richard: Okay, as far as nurturing the body through knowledge, is the goal of what you teach to eliminate obstacles in . . .?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: That is the goal?

Prabhupāda: Everything is aimed at to eliminate obstacles. Now, so far the body is concerned, there are so many obstacles. Everyone is struggling hard, that is for struggle for existence, to get out of the obstacles. Whole struggle for existence is to save ourselves from the obstacles.

Richard: Right. How do you determine what's an obstacle?

Prabhupāda: Obstacles . . . the ultimate obstacle is that you don't like to die, but you can die any moment. This is greatest obstacle. Why don't you think of it? You are sitting here, you are young man. So you may die immediately.

Richard: Uh-huh.

Prabhupāda: That is the greatest obstacle. You have got so many plans to do in your life, but you can die any moment. Is it not obstacle?

Richard: The presence of death or the possibility of death?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Um, to me, I don't think really it is, for me.

Prabhupāda: Why? Why not? You don't like to die.

Richard: I don't think . . . that doesn't bother me.

Prabhupāda: It bothers. Suppose you have got some plan you have to do—everyone has got some plan, ideas, some improvement—but where is the guarantee that you'll be able to execute that plan? Because you can die at any moment.

Richard: Right, there is none.

Prabhupāda: So it is not obstacle?

Richard: No.

Prabhupāda: How is that, is not obstacle? You are planning something that, "I shall do this." You may not be very important man, but there are many important men. The leaders of the society, they are planning that, "I shall make my nation like this way, my family like this way." Everyone is planning. But where is the guarantee that he'll be able to fulfill the plan? Death may take place any moment. So is it not obstacle?

Richard: Hmm. I really don't view it as an obstacle, the fact that my plans may be altered.

Prabhupāda: You may not. You may not, but we have got personal experience that people do not want to die until he fulfills some . . . his brainwork plan. You see? I have seen. One, my friend, he was dying, he was at that time fifty-four years old only, and he was begging the doctor, "My dear doctor, medical man, can you not give me four years' time only, I can fulfill my plan?" He was very big businessman, so he was planning something to do, but doctor said that, "You cannot survive." So he was begging the mercy of the doctor, "Doctor, can you not give me at least four years' time?" As if the doctor can give him life. He was feeling this is obstacle, "I'm going to die without fulfilling my plan." I think that psychology is everywhere.

Richard: But . . . but generally, how can . . .?

Prabhupāda: You may not be afraid of, but generally.

Richard: Generally, how can you determine an obstacle . . .

Prabhupāda: I've seen it, I've seen it, that he was begging the doctor, "Please give me four years' life. Give me some medicine so that I'll live at least for four years, I'll finish my plan." I've seen it. You are the first man that you are not afraid of death, (devotees laugh) but I see everyone is afraid of death.

Richard: I . . .

Prabhupāda: You see. As soon as there is immediately siren, I've seen it, also . . .

Richard: Are you afraid of death?

Prabhupāda: No. My position is different, because I know I'm not going to die. My position is different. Because we are confident, na hanyate hanyamāne śarīre (BG 2.20). We are not going to die. Death is no question for us.

Richard: Um-hm. Okay.

Prabhupāda: Therefore we are not afraid of death. That is another thing. But generally, people, they are actually . . . are you not afraid of disease?

Richard: I would not wish to be in great pain or agony, no.

Prabhupāda: But there is pain. As soon as you are in disease, there is great pain.

Richard: Uh, yes, but there are quick deaths and there are slow deaths.

Prabhupāda: No, everyone is afraid of this. Are you not afraid of old age and invalidity?

Richard: Not particularly. I mean, it's a part of life.

Prabhupāda: You are liberated. (devotees laugh)

Rāmeśvara: Prabhupāda said you are liberated.

Richard: I'm what?

Rāmeśvara: Liberated.

Richard: Oh. (laughs)

Prabhupāda: Naturally, everyone, that is the problem of life. Otherwise, why there are so many medical colleges, drug shops and medicines, just to avoid disease? Otherwise, there was no need of arrangement. Everyone is afraid of disease, not to suffer from disease. That's a fact. If you say that you are not afraid of disease, that is something new. But unless we are afraid of disease, why there is this Memorial Hospital, this drug shop, this pharmacy? Why these things are required? We don't want it.

Richard: Do you . . .? You have a doctor, though, you said, right?

Prabhupāda: No, I am not a doctor.

Richard: You have no doctor.

Prabhupāda: My point is that these are the problems—birth, death, old age and disease. This is our point.

Richard: That these are the basic problems of most men?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Death, fears of death and disease.

Prabhupāda: Yes, everyone.

Richard: You too?

Prabhupāda: Everyone. I am everyone also. I am also, I have taken up my translation work, Bhāgavatam. So I am trying to live at least up to the time I finish my translation. That is also . . . I do not wish to die before I finish. That is also . . . everyone is like that.

Richard: But what happens if you do die before you finish?

Prabhupāda: Well, you are talking something extraordinary. Everyone has got some ambition, and he wants to do it, and death, disease, old age, these are impediments. That is the point. No one wants to die premature death.

Richard: What is a premature death?

Prabhupāda: Family man, a family man wants to see that his sons are properly educated or they are well-placed, so on, so on, so many things. And if all of a sudden death comes, he becomes sorry that, "I could not finish my business." Therefore death is impediment.

Richard: You were widely respected in India before you came to the United States?

Prabhupāda: Why bring that question? First of all, let us finish this question.

Richard: Well, no, no, no. I'm getting to it. Ah, if you had died before you had come to the United States, would that have been a tragedy?

Rāmeśvara: Yes, that would have been a big tragedy for all of us. That is premature. That's the example Prabhupāda is giving. If a man wants to educate his sons, but he dies before they can be educated, then, to him, that is a premature death. So therefore he does not want that. In fact he's afraid, "Please, I don't want to die before I see my sons educated." So that is a fear of death.

Prabhupāda: Therefore death is an obstacle. That is the point.

Rāmeśvara: An obstacle to the goals of his life.

Prabhupāda: One who has no responsibility, that is another thing. But a responsible man wants to finish the responsibility, and if death comes before that, that's an obstacle.

Richard: Um-hm. Okay. Ah, how about smaller obstacles in life, though, than death? I mean this . . .

Prabhupāda: This is the major obstacles, and subordinate to these obstacles there are hundreds and millions of obstacles.

Richard: There are millions of obstacles.

Prabhupāda: Yes, this is the main obstacle.

Richard: Right, right, okay. But I mean, okay, you say most people are . . . almost everyone, except me perhaps, is concerned about death. Ah, but how about the smaller obstacles which nevertheless can make people very depressed today, neurotic? How do you recognize and live with them or eliminate them?

Prabhupāda: Our point is there are hundreds and millions obstacles. If they are, I mean to say, summarized, they become birth, death, old age and disease. This is my point. There are hundred and thousands of obstacles, but if you take all of them and make a summary, then it comes four—birth, death, old age and disease.

Rāmeśvara: He wants to know, Śrīla Prabhupāda, if these are the obstacles, how do we Kṛṣṇa conscious people deal with these obstacles or eliminate these obstacles?

Prabhupāda: Yes, that we are doing by Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement.

Richard: How?

Prabhupāda: Because if we try to understand Kṛṣṇa, simply by understanding Him, I am going to get a life which will be free of all obstacles.

Richard: And how do you do that?

Prabhupāda: That you see what we are doing.

Richard: By living this type of life?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Well, what about the people who don't live here at the āśrama, people who live, if you want to call it, the outside world, ah . . .

Prabhupāda: They are not getting the opportunity. We are giving the opportunity. You come here and live here.

Richard: This is the only way?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Living in an āśrama.

Prabhupāda: Not living . . . to take the philosophy. Follow the policy or process; then your life is successful.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Just like our householders, they have their apartments, but they're always associated with Kṛṣṇa's service.

Richard: Right.

Prabhupāda: Just like we are writing so many books to give them enlightenment. This is the process. It is an educational movement, how to overcome these obstacles. That is the sum and substance.

Richard: Do you think there are any other ways which are equally effective?

Prabhupāda: No.

Richard: Isn't the spiritual benefit that people in the āśrama here get . . .

Prabhupāda: First of all, he must know what is spirit. They do not know even what is spirit.

Richard: Well, okay, there are many contented people in the world, there are many people who are at peace with themselves . . .

Prabhupāda: Contented . . . ass is contented. He has no problem. The best-contented living being is an ass. He has no complaint. So that is not civilization.

Richard: That is not what?

Prabhupāda: That is not civilization, or life.

Richard: Okay, but being able to live with your limitations and be therefore content, ah, within those limitations . . .

Prabhupāda: That I already said, that animal lives very contented within his limitation. He doesn't like to improve. But that is not human life.

Richard: Well, okay, ah, but I know many people who are relatively contented and still growing.

Prabhupāda: What is the contentment? If you have got the problems unsolved, that is ass's contentment. Ass does not know how to check death. He does not think of it. But a human being's intelligence says whether the disease can be checked, whether the death can be checked. That is human being. The ass cannot think. If we remain contented like an ass, so that is animal life.

Richard: Right, but still people carry on, people . . .

Prabhupāda: Let them carry on. Ass is also carrying on. That is another thing. But distinction between ass's life and human life, the ass cannot estimate the impediments or the obstacles of life. A human being can see, and it is his duty how to overcome it.

Richard: Pardon me while I get that down. Um, yeah, okay. I guess what I'm saying then is that I know many people who do not live in āśramas, who will . . .

Prabhupāda: I am not advising that you live in āśrama, but . . . just like here is an . . . you see, McGill University. So they are giving permanent order of our books. So the university authorities, they are not coming to our āśrama, but they'll get the benefit by reading our books.

Richard: Right. Okay. But I know people who have not had the benefit of reading your books, and yet, as far as I know, and I've gotten to know them very well, they seem to be living lives which, for them, work. The obstacles they can cope with, and I guess what I'm saying is, or advancing, is that perhaps the . . .

Prabhupāda: There are many men who do not go to the university and live peacefully. But that does not mean university is useless. Similarly, many men may not come to us, that does not mean this institution is useless. It has its importance for the serious men, not for the asses.

Richard: Right, but do you think . . .

Prabhupāda: Just like this university, they are serious for education, they are ordering our books. Others may not order; they are not reading. That means they are not serious.

Richard: Only the people who are . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. Knowledge is for the intelligent class of men.

Richard: But there are many types of knowledge, and there are many ranges, depths of knowledge.

Prabhupāda: So, if many types, this is also one type of knowledge.

Richard: Right, it is not the only type, that's what I'm . . .

Prabhupāda: No, there are different aims also. If you are interested to become an expert medical man, then the knowledge is different. If you want to become an engineer, the knowledge is different. Similarly, if he wants to overcome all the obstacles, then this is the education.

Richard: Um-hmm.

Prabhupāda: This is the final.

Richard: What about other religions?

Prabhupāda: Other . . . you become interested in medical, you become a medical man, you become an engineer, you become other . . . you take that education. But one who is interested to stop all obstacles of life, this is the only education.

Richard: This is the only one.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Have you studied other religions?

Prabhupāda: Yes, therefore I'm saying. Without studying, how can I say? I am challenging, not saying. We are challenging. We are not saying only.

Richard: Um-hm.

Prabhupāda: If you want to overcome all obstacles of life, this is the only education. That's all. Or if you have different aims of life, there are different departments of knowledge. But if you want this knowledge, then this is the education.

Richard: And according to you, this is the only spiritual knowledge.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: What you write about and have studied.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: What would you classify, ah, other works, say, the Koran or the Bible or any other religious . . .

Prabhupāda: Well, they are also aiming to this aim of life.

Richard: They are in the same aim.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Yes.

Richard: But do you think they are successful?

Prabhupāda: They are successful if they follow the education. Just like Christ, he's speaking of kingdom of God. So if you follow Christ, there is hope that you go to kingdom of God. But if you don't follow, you simply rubberstamp, "I am Christian," then it is useless.

Richard: But there are other . . .?

Prabhupāda: Yes, they are of the same type.

Richard: Yes, but do they have any value as far as you are concerned?

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes, they have value.

Richard: Okay, that's what I was trying to get at.

Prabhupāda: There is value.

Rāmeśvara: Prabhupāda meant that the other branches of knowledge outside of religion . . .

Richard: Oh, yes, right. I wasn't talking about that.

Rāmeśvara: That was mis . . .

Richard: Right, I wasn't talking about a technical or secular knowledge at all. I was talking about other spiritual philosophies.

Prabhupāda: No. Any science, any knowledge who is trying to give enlightenment about God, there is the same line as we are doing.

Richard: Right. But those people who study, say . . . okay, to use an example, the Pope. Now there is a man who has dedicated his whole life, publicly, personally, spiritually, however you define it, to Christianity, specifically to the Catholic Church. Now apparently, and for all intents and purposes, his life seems to work for him.

Prabhupāda: The thing is, the Catholic Church is the original Church, I think.

Richard: The original Christian Church, yes.

Prabhupāda: So then why there are so many varieties?

Richard: Well, because . . .

Prabhupāda: Now hundreds and thousands of churches are there.

Richard: Right. Other people find that . . .

Prabhupāda: So that means they don't like Catholic Church. They don't like. So they are missing the point.

Richard: Of the Catholic Church.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: True, I agree. But is the point of the Catholic Church the only point that's to be made?

Prabhupāda: And if you accept Christianity, then the Catholic process, I think—I do not know—that is only way.

Richard: But is the point that the Catholic Church makes the only point to be made?

Prabhupāda: Not Catholic. I mean to say, any church original, authoritatively, that is genuine. If you deviate from that, then you cannot claim to that school.

Richard: Granted.

Rāmeśvara: It's an example that if the Catholic Church is presenting the teachings of Jesus as it is, and then later on other churches deviate a little, then to deviate from the teachings of Jesus is bad, and to stick strictly to the teachings of Jesus is the only way, in Christianity. That's the idea.

Richard: Yes, but the goal is similar in Christianity.

Prabhupāda: The goal cannot be similar. If you deviate, the goal is different.

Richard: No, no . . . the . . . okay, the goal generally is the same.

Prabhupāda: General is no question. Goal is one, so if you deviate, then you go away from the goal.

Richard: Right, but the goal seems to me, as I have studied Christianity . . .

Prabhupāda: What is the goal?

Richard: The goal of Christianity is to make a better life here on earth for the followers of Christ and after death.

Prabhupāda: That's nice. That is our preaching also.

Richard: That's your goal also.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Okay . . .

Prabhupāda: Just like a student is being trained up in medical college, and when he becomes practitioner, the same thing. There is no change. There is no change.

Richard: Yes, I think you are talking about specific . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no, this is . . . take Christian religion. So to going to the church, it is practicing how to establish relationship with Christ and God. So after death, if he's perfect, he goes back to home, back to Godhead.

Richard: Um-hm, right.

Prabhupāda: So this is practice. If one is interested in going back to home, back to Godhead, then this is the only way.

Richard: Okay, let me just say something, and then, you know, like, you can take it however you want. It seems to me that there, all through life, men, all through history, men have been more or less striving for this same general goal—happiness here and here . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no, same general goal . . . you must speak . . . if you say same general goal, everyone says: "This is also general goal, this is also general goal." You must specifically mention what is that.

Richard: Okay, that goal is happiness here on earth, and however you define happiness—security, well-being, food on the table, however you want to—and . . .

Prabhupāda: But if somebody says that, "I don't require to go to church for happiness. I find happiness by drinking. Let me go to the brothel and drink," that is also happiness. You cannot say. They can say: "I don't care to go to the church. I am getting happiness here."

Richard: I'm thinking of it in a larger sense than that.

Prabhupāda: Happiness must be happiness. It doesn't mean that because larger accepts something happiness, that is happiness. No. Happiness must be real happiness.

Richard: Okay, what do you define as real happiness?

Prabhupāda: One may like it or not like it, that is not the question. Happiness is real happiness.

Richard: Right. Okay, that's what I'm talking about, spiritual happiness.

Prabhupāda: So if you simply say happiness, if you do not explain what is real happiness, then somebody will say, "I'm feeling happiness by drinking here. Why you are asking me to go to the church? You go, I don't go." That's all. Then you have to explain what is real happiness—whether that real happiness is obtainable by going to the church or going to the brothel, liquor house.

Richard: Well, I don't think that any . . .

Prabhupāda: You don't think, but he thinks that, "Here is happiness." You cannot induce him. He thinks. Just like few minutes ago you said that there is no obstacle, but we think there is obstacle. There is different thoughts. They don't care what is God, what is . . . "I don't want to know what is God. I'm getting happiness," finished.

Richard: Okay, but continuing, you know, continuing, people are, okay . . . people, I think, are basically the same in many respects as far as . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no, that is wrong. That is wrong.

Richard: That is wrong. Okay, why?

Prabhupāda: You see, I have already explained. One is getting happiness by drinking, and one is getting happiness by going to the church. You cannot say that they are the same.

Richard: Well, I think they're the same in intent.

Prabhupāda: Now, what do you mean by that? First of all, describe what is happiness, whether drinking is happiness or going to the church is happiness. Therefore you have to define what is happiness. Then we have to select whether this happiness is obtainable in the liquor shop or in the church. You must have clear idea of happiness. And if you speak generally, then he will say: "I am getting happiness; why you are insisting me go to the church? I am getting happiness." Therefore you have to define what is happiness.

Richard: Okay, I would say happiness is the pursuit of, to you, what makes your life work, worthwhile.

Prabhupāda: We are not working, we are not interested in working.

Richard: Well, when I say work, I mean what gives you an inner respect for yourself, um . . . I think it all boils down to self-respect, an appreciation of . . .

Prabhupāda: What is this self-respect?

Richard: Self-respect? Self-respect would be an appreciation and cognizance of your spiritual and physical being.

Prabhupāda: So what is my actual being? Physical being or spiritual being?

Richard: Both. I mean they are part of, to me, they are one manifestation.

Prabhupāda: And after death what happens?

Richard: Do I feel personally?

Prabhupāda: No, everyone.

Richard: I think everyone has different ideas. There are many different ideas about what happens after death.

Prabhupāda: Therefore we have to know what is reality.

Richard: What is . . .?

Rāmeśvara: Reality.

Richard: Reality.

Prabhupāda: Therefore we have to know what is reality. Simply ideas will not do.

Richard: Okay, reality I would say is . . .

Prabhupāda: And if you do not know, how you will say? You say that you do not know, but how you will say, if you do not know what is reality?

Richard: Oh, I know what reality is.

Prabhupāda: What is that?

Richard: Reality is a series of moments or a moment perceived by the senses.

Prabhupāda: That I have already explained. The drunkard is feeling by drinking his senses are very satisfied, that is reality.

Richard: Sure, it's his reality.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Then why should you canvass him, "Please come to the church and accept Christianity"?

Richard: Frankly, I don't know. I don't really know why he should be asked to go to church.

Prabhupāda: Therefore . . . then there is no need of church. Everyone can do whatever he thinks reality. That is no standard reality.

Richard: No, reality is not in itself a goal. It just is.

Prabhupāda: Then what is the goal?

Richard: I would say, you know, we discussed this earlier, it's a, er, it's trying to find what makes one's life worthwhile.

Prabhupāda: "Trying to find," that means you do not know.

Richard: No, I think life is a pursuit. I don't think it . . .

Prabhupāda: What is that pursuit if you have no aim or objective? You are going to the school, the object is you become a graduate. If you do not know what is the ultimate goal, what is this pursuit?

Richard: Why pursue something? . . . (indistinct)

Prabhupāda: You are going to school, college, suppose you are going to be graduate. But if you do not know what is the ultimate end of pursuit, then what is this pursuit? Simply blind?

Richard: No, it's . . . it's just trying to make your life work.

Prabhupāda: There must be some goal, ultimate goal. That we must know. That is called pursuit. If you do not know what is the ultimate goal of life, then there is no meaning of pursuit.

Richard: Um.

Rāmeśvara: Prabhupāda is talking about an absolute reality, not a relative reality.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: What is your definition of an absolute reality?

Prabhupāda: That is final.

Richard: A goal.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Okay, and what is the absolute reality?

Prabhupāda: Relative means it is understood in two ways. Absolute means there are no two ways. Final. We say it is final. So what is the final aim of our life, that we must know.

Richard: Do you know?

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes, we know, everyone, all of our students.

Richard: What is that absolute reality that is the absolute goal?

Rāmeśvara: The absolute goal is to understand that within this body there is a living force which is spiritual, and that spiritual force is a servant of God. It has a relationship with God. Apart from how you perceive the world through your senses, beyond that there is a soul which has a relationship with God. That is the absolute reality. You may perceive the world in so many ways through your senses, but beyond that, within your body there is a soul which is yearning for a relationship, a loving relationship with God. And if you neglect that relationship due to your senses . . .

Prabhupāda: Ignorance.

Rāmeśvara: . . . or ignorance, then you're missing the reality of life and you're living in an illusion. Due to your senses you're living . . . you could live . . . be living in illusion. The senses are not perfect instruments for understanding reality. There is another process for understanding reality. The senses are not perfect. Therefore one should not depend upon the senses to understand reality. There is a greater process.

Richard: And how is that found?

Prabhupāda: You find out this verse: sukham ātyantikaṁ yat tad atīndriyaṁ grāhyam.

Rāmeśvara: What's the second word, Śrīla Prabhupāda?

Prabhupāda: Sukham ātyantikam.

Rāmeśvara:

- sukham ātyantikaṁ yat tad

- buddhi-grāhyam atīndriyam

- vetti yatra na caivāyam

- sthitaś calati tattvataḥ

- (BG 6.21)

Prabhupāda: Translation?

Rāmeśvara: It's combined with some other verse. "The stage of perfection is called trance, or samādhi, when one's mind is completely restrained from material mental activities by practice of yoga. This is characterized by one's ability to see the self by the pure mind and to relish and rejoice in the self. In that joyous state one is situated in boundless transcendental happiness and enjoys himself through transcendental senses. Established thus, one never departs from the truth, and upon gaining this he thinks that there is no greater gain. Being situated in such a position one is never shaken, even in the midst of greatest difficulty. This indeed is actual freedom from all miseries arising from material contact."

Prabhupāda: That is translation?

Rāmeśvara: That is the translation.

Prabhupāda: Purport.

Rāmeśvara: Purport. "By practice of yoga one becomes gradually detached from material concepts. This is the primary characteristic of the yoga principle, and after this one becomes situated in trance, or samādhi, which means that the yogī realizes the Supersoul through transcendental mind and intelligence, without any of the misgivings of identifying the self with the Superself. Yoga practice is more or less based on the principles of the Patañjali system. Some unauthorized commentators try to identify the individual soul with the Supersoul, and the monists think this to be liberation. But they do not understand the real purpose of the Patañjali system of yoga. There is an acceptance of transcendental pleasure in the Patañjali system, but the monists do not accept this transcendental pleasure, out of fear of jeopardizing the theory of oneness. The duality of knowledge and knower is not accepted by the nondualist, but in this verse transcendental pleasure realized through transcendental senses is accepted, and this is corroborated by the Patañjali Muni, the famous exponent of the yoga system. The great sage declares in his Yoga-sūtras: puruṣārtha-śūnyānāṁ guṇānāṁ pratiprasavaḥ kaivalyaṁ svarūpa-pratiṣṭhā vā citi-śaktir iti."

"This citi-śakti, or internal potency, is transcendental. Puruṣārtha means material religiosity, economic development, sense gratification and, at the end, the attempt to become one with the Supreme. This oneness with the Supreme is called kaivalyam by the monist. But according to Patañjali, this kaivalyam is an internal, or transcendental, potency by which the living entity becomes aware of his constitutional position. In the words of Lord Caitanya, this state of affairs is called ceto-darpaṇa-mārjanam (CC Antya 20.12), or clearance of the impure mirror of the mind. This clearance is actually liberation, or bhava-mahā-dāvāgni-nirvāpaṇam. The theory of nirvāṇa—also preliminary—corresponds with this principle. In the Bhāgavatam this is called svarūpeṇa vyavasthitiḥ (SB 2.10.6). The Bhagavad-gītā also confirms this situation in this verse."

"After nirvāṇa, or material cessation, there is the manifestation of spiritual activities, or devotional service of the Lord, known as Kṛṣṇa consciousness. In the words of the Bhāgavatam, svarūpeṇa vyavasthitiḥ: this is the real life of the living entity. Māyā, or illusion, is the condition of spiritual life contaminated by material infection. Liberation from this material infection does not mean destruction of the original, eternal position of the living entity. Patañjali also accepts this by his words kaivalyaṁ svarūpa-pratiṣṭhā vā citi-śaktir iti. This citi-śakti, or transcendental pleasure, is real life. This is confirmed in the Vedānta-sūtras as ānandamayo 'bhyāsāt (Vedānta-sūtra 1.1.12). This natural, transcendental pleasure is the ultimate goal of yoga and is easily achieved by execution of devotional service, or bhakti-yoga. Bhakti-yoga will be vividly described in the Seventh Chapter of Bhagavad-gītā." Should I keep reading, Śrīla Prabhupāda?"

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Rāmeśvara: Should I continue?

Prabhupāda: There is still there?

Rāmeśvara: There is another page.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Rāmeśvara: "In the yoga system, as described in this chapter, there are two kinds of samādhi, called samprajñāta-samādhi and asamprajñāta-samādhi. When one becomes situated in the transcendental position by various philosophical researches, it is called samprajñāta-samādhi. In the asamprajñāta-samādhi there is no longer any connection with mundane pleasure, for one is then transcendental to all sorts of happiness derived from the senses. When the yogī is once situated in that transcendental position, he is never shaken from it. Unless the yogī is able to reach this position, he is unsuccessful. Today's so-called yoga practice, which involves various sense pleasures, is contradictory. A yogī indulging in sex and intoxication is a mockery. Even those yogīs who are attracted by the siddhis, or perfections, in the process of yoga are not perfectly situated. If the yogīs are attracted by the by-products of yoga, then they cannot attain the stage of perfection as is stated in this verse. Persons, therefore, indulging in the make-show practice of gymnastic feats, or siddhis, should know that the aim of yoga is lost in that way."

"The best practice of yoga in this age is Kṛṣṇa consciousness, which is not baffling. A Kṛṣṇa conscious person is so happy in his occupation that he does not aspire after any other happiness. There are many impediments, especially in this age of hypocrisy, to practicing haṭha-yoga, dhyāna-yoga and jñāna-yoga, but there is no such problem in executing karma-yoga or bhakti-yoga."

"As long as the material body exists, one has to meet the demands of the body, namely eating, sleeping, defending and mating. But a person who is in pure bhakti-yoga, or in Kṛṣṇa consciousness, does not arouse the senses while meeting the demands of the body. Rather, he accepts the bare necessities of life, making the best use of a bad bargain, and enjoys transcendental happiness in Kṛṣṇa consciousness. He is callous toward incidental occurrences—such as accidents, disease, scarcity and even the death of a most dear relative—but he is always alert to execute his duties in Kṛṣṇa consciousness, or bhakti-yoga. Accidents never deviate him from his duty. As stated in the Bhagavad-gītā, āgamāpāyino nityās tāṁs titikṣasva bhārata. He endures all such incidental occurrences because he knows that they come and go and do not affect his duties. In this way he achieves the highest perfection in yoga practice."

Richard: Did you write . . . you wrote the purport? Okay, um, when you said that the person who is involved with Kṛṣṇa consciousness makes the best use of a bad bargain, were you referring to life?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: This physical life?

Rāmeśvara: Physical.

Richard: Okay.

Prabhupāda: The physical life is struggle for existence.

Richard: Is a struggle for existence. Why is . . .? Why, if a man who is an alcoholic, if that's the best that he can make of life, why is that bad?

Prabhupāda: That is not . . . he's wrongly . . . he's going in the wrong path.

Richard: Well, if that's the best that he can do.

Prabhupāda: He can think.

Richard: He can change?

Prabhupāda: Yes, he can change. Change is possible, but if he sticks, that is his selection.

Richard: Ah, but suppose drinking to him is better than what he has to put up with, the . . .

Prabhupāda: That is not actual fact. Drinking, nobody can be happy by drinking. That is not possible.

Richard: Okay. Okay. You said in the purport that tragedies of life—I'm paraphrasing—tragedies of life such as death of even a close relative are mere incidental occurrences. Is . . .? But you said earlier that death to you was anything but a mere incidental occurrence, that it was the . . . am I mis . . .

Prabhupāda: No, we are not irresponsible to the death. Death, although we have to meet death, we are making provision that after death we become happy. Happy, of course, for us, even in living condition or dead condition, there is happiness, but it will take time to understand. But taking superficially, death is not very pleasing, so after death, that is mentioned in the Bha . . . tyaktvā dehaṁ punar janma (BG 4.9), we do not get again a material body. This is final. The material body is the cause of pains and pleasure. So if you don't get the material body, if you remain in your spiritual body, that is real enjoyment.

Richard: But then why do you fear this death of the physical body?

Prabhupāda: No, I do not fear.

Richard: Oh, you don't?

Prabhupāda: No.

Richard: Oh, okay.

Rāmeśvara: The ordinary man.

Prabhupāda: Because . . .

Richard: Well, I don't either, and I'm not in Hare Kṛṣṇa.

Prabhupāda: That is another thing, because you do not know that you are risking your life without Kṛṣṇa consciousness. That is the . . . you do not, that I have already said, that an innocent person doesn't know what is going to happen. But things are going to happen. That you do not know.

Rāmeśvara: After death.

Prabhupāda: So you must be aware what is going to happen after death. Then if you become fearless, that is secure. But without knowing, if you are not afraid, that is risky.

Richard: Okay. Are you familiar with the writings of Descartes?

Prabhupāda: We don't read anyone's book except Bhagavad-gītā.

Richard: Oh, I thought you said you studied other philosophies.

Prabhupāda: Study, there are so many books we studied.

Richard: Right, okay, well anyway, there was a French philosopher in the 1700s named Rene Descartes, and his . . .

Prabhupāda: I think we have discussed this philosopher.

Rāmeśvara: Yes.

Richard: You have discussed him? All right, one of the things he said was that . . . oh, no, I'm sorry, it's Pascal. I'm sorry. Descartes said something else. I'm thinking of Pascal. Anyway, same thing practically. Ah, he said that as far as an afterlife goes, as far as proving it, it's impossible to prove it.

Prabhupāda: Why impossible? He does not know.

Richard: Okay.

Prabhupāda: We can prove immediately.

Richard: Okay, but it's just a wager, it's a moot argument. The proofs are of a spiritual kind rather than a . . .

Prabhupāda: It requires little brain; otherwise, it can be proved immediately.

Richard: Pardon me, I didn't catch the last part.

Prabhupāda: This, that the spirit soul is there, that can be proved immediately provided one has brain to understand.

Richard: How do you prove that a spirit is dead?

Prabhupāda: That is very easy. Just like you are a young man . . .

Rāmeśvara: Prabhupāda said "spirit is there."

Richard: Oh, oh, I misunderstood.

Rāmeśvara: Not that "spirit is dead." Spirit is there.

Richard: Oh, oh. Okay I misunderstood.

Prabhupāda: Just try to, try to . . .

Rāmeśvara: Just like when you have a very . . . when you were first born, you have a very small body. Now you are older. So where is that small body? It is no longer existing. Now you are in a young man's body. So similarly, when you are sixty years old, the body that you have now will no longer exist, but you still exist. Even though your body has changed, your life goes on. In other words, life is not dependent on the body. The body changes.

Richard: Yes, but you still have a body at sixty.

Rāmeśvara: Death is another change of body. Life will go on. The example of life going on even though you are changing your body, you are experiencing within this one life. You've already experienced that your life goes on even though you have changed your body so many times. So death is simply another change of body. But you have already experienced that you can exist even though you have quit one body and got a new body.

Prabhupāda: Now the point is that you are going to get another body. That's a fact.

Richard: How do you know that?

Prabhupāda: Now what kind of . . .? This is a fact, just like you have got already another body. Where is that child's body? Where is that boy's body? That is finished. This is the proof.

Richard: But I'm still alive.

Prabhupāda: Alive, you are always alive.

Richard: Physically alive.

Prabhupāda: No, physically not. Spiritually, you are always alive. This point is to be understood. The death taking place only of the physical body. That you have to understand.

Richard: Right, but I have never been aware of any proof . . .

Prabhupāda: That is education. You are not aware because you are not educated.

Richard: Perhaps, but I have never read of anyone else actually proving that there is a spiritual afterlife.

Prabhupāda: Here is the proof, he is giving proof. Therefore I said it requires little brain. He's giving proof.

Richard: I think it requires more than education; it requires faith.

Rāmeśvara: The first question Prabhupāda asked is what is the difference between a dead man and a living man. The body is the same, but something is missing in the dead man, in the dead body. So that is the proof that the body is not living at any time, but there is a living energy, and when that living energy is inside the body, it makes the body seem alive, and if that living energy is taken out of the body, then the body is seen as it really is, a lump of matter. The body is never alive; it is the presence of the soul within the body that animates the body.

Richard: Right, okay, that's what animate, that's the etymology of animation, anima, soul.

Rāmeśvara: So your body . . .

Richard: I agree with all that. I agree with all that.

Rāmeśvara: And that living energy is eternal, and when this body becomes an old man's body, or rather when you get an old man's body, the body you have now will be finished, but you will still be alive because you are that eternal living energy.

Richard: Okay, and what I am saying is that I have . . . there has never been any empirical proof of that.

Rāmeśvara: But I have already explained that these senses are not the perfect instruments for experiencing reality. Just like sometimes there may be a cloud, and therefore you cannot see the sun with your senses. But that does not mean the sun is not there. It simply means your senses are not powerful enough to see. The senses are imperfect instruments for perceiving reality. The sun is always there, but sometimes you can see it and sometimes you can't.

Prabhupāda: Just like night, this is night, you don't see the sun. That does not mean there is no sun.

Rāmeśvara: Don't rely on empirical sense perception.

Richard: Okay, right, you're introducing here, though, the essence of all religion, that is faith. Faith . . .

Prabhupāda: It's not faith, it is fact. If I say that there is sun and you cannot see, if you deny, "No I don't see. There is no sun," so which is fact?

Richard: Well there is no sun now. There's no sun present.

Prabhupāda: Sun is there. You cannot see.

Richard: Right now, the sun, in my life, is not present.

Prabhupāda: It is present. That is ignorance. You just phone immediately to Bombay, "Is there sun?" He'll say: "Yes."

Richard: Is the sun out in Bombay?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: I have faith that it is.

Prabhupāda: No faith. It is fact.

Richard: It is a fact, not to me though.

Prabhupāda: No, then you are not very intelligent. You phone your friend that, "Where is the sun?" He'll say: "It is above my head."

Richard: Right now, the sun is not above my head.

Prabhupāda: Not your head, but you phone to your friend in Bombay, he'll say: "Yes, here is sun." But that does not mean you don't believe in the sun existing. That's not fact.

Richard: No, that's not what I'm talking about. I'm saying . . . you asked me whether the sun was above my head now, and I said no it is not, but that does not mean . . .

Prabhupāda: Head or not head, sun is there, but you cannot see. That is the point.

Hari-śauri: Prabhupāda is explaining the existence of the sun is not dependent upon your perceiving it through your senses. The sun is always there, but sometimes you perceive it and sometimes you don't.

Prabhupāda: You don't perceive. That is your position.

Richard: Right. That is because I am physically limited by my body.

Prabhupāda: Yes, that is the point. That is the point.

Richard: But I still don't see that as an affirmation nor as a denial.

Prabhupāda: Therefore this verse is explained to you, sukham ātyantikaṁ yat tad atīndriyaṁ grāhyam (BG 6.21). So we have to understand through supersenses, not this blunt senses.

Richard: Right, and I think . . .

Prabhupāda: These are imperfect.

Richard: And I think that in the Western world—I don't know about the Eastern world—in the Western world, that understanding is called faith.

Rāmeśvara: No, what Prabhupāda is explaining is . . . just like now you are seeing me through your blunt senses. By the process of Kṛṣṇa consciousness, you awaken a different type of senses, called transcendental senses, and it is just as real as the blunt sense perception, except it is perfect sense perception, whereas your physical senses are conditioned, limited. There are transcendental senses.

Richard: Yes, but all the input goes into the mind, right?

Rāmeśvara: No, these are actual sense perceptions. "The soul is sentient, thou has proved."

Richard: Okay.

Rāmeśvara: Just like your body has senses, the soul also has senses, and the process of Kṛṣṇa consciousness, chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa and taking the spiritual prasādam, seeing the Deity in the temple and hearing this Vedic knowledge, that awakens the soul, and thus you can experience the sense perception of the soul, the knowledge of God through the soul, sense perception. You can see God, when you're very pure. And that's a fact, not faith.

Prabhupāda: There are five stages of ascending to come to the right conclusion. This, this is . . . just like pratyakṣa, directly, you do not see the sun on the sky, but the same example, if you phone your friend, "Where is the sun?" then he'll say: "Yes, here is the sun." So this is called parokṣa, mean you get the knowledge by other sources. Your direct sources, you cannot see, but you get from other sources, you understand, "Yes, sun is there in the sky."

Richard: And I have faith that it is.

Prabhupāda: You must have faith.

Richard: I trust that it is.

Prabhupāda: You have to trust.

Richard: Okay, I was listening to him and, you know, I'm hearing a lot . . . okay, the brain . . .

Prabhupāda: I mean to say, there are five stages: pratyakṣa, parokṣa, aparokṣa, adhokṣaja and aprākṛta. So our process should be to go to the aprākṛta, transcendental knowledge. This is the stages. Just like . . . this is explained. We can directly understand that by directly, I'm seeing there is no sun, but when I ask my friend, he says there is sun. So this is also knowledge. This is called parokṣa knowledge—from other sources. Similarly, there are stages. So when the perfect stage is, that is aprākṛta, no more material, all spiritual.

Richard: Okay. The brain, the mind, interprets the senses . . .

Prabhupāda: Brain, mind, they are instruments.

Richard: Okay, they interpret the senses. Right. Okay.

Prabhupāda: Yes, they are instruments.

Richard: Now if the . . .

Prabhupāda: Suppose if you see with your eyes, and then you see with microscope, then you see with telescope—different processes. Yes. But when you see with your spiritual eyes, that is perfect.

Richard: Now suppose the brain dies, as in the case . . .

Prabhupāda: Brain dies . . . brain is part of the body.

Richard: Right, it's a part of the body. It can fail, just as the heart or the lungs or anything else. Okay. Now suppose the brain dies, the soul . . .

Prabhupāda: You get another brain.

Richard: Pardon me?

Prabhupāda: You get another brain. Suppose, just like you are working with the glass, spectacle, it breaks, you get another spectacle. That's all.

Richard: In the same body?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Richard: Okay, now Karen Ann Quinlan, you know her?

Prabhupāda: We don't know anyone.

Richard: Okay, this is a . . . let me explain very briefly. Here is a girl in New Jersey, near New York, whose brain has died through a traffic accident. Her body is still alive. Her body is still alive, but her brain is dead; she cannot get up, speak, move.

Prabhupāda: This is already explained, the brain is an instrument. The instrument is not working, but that is not death.

Richard: Right, her soul is still alive, is that correct?

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes.

Richard: Her soul is still alive, and she is still functioning spiritually, even though her brain is dead. Is that what . . .?

Prabhupāda: That is possible, because soul is there.

Rāmeśvara: The soul is always alive, but the fact that she's being maintained means the soul's still in that body, has not left the body yet.

Richard: Okay, now what . . .

Rāmeśvara: The soul is always living.

Richard: Okay, now what is . . . is the soul in a . . .

Prabhupāda: That is another proof. That instead of . . . in spite of the brain is not working, the soul is there.

Richard: Okay, but just let me finish this, and then we'll leave it. The . . . okay, how am I going to say this? Is her spiritual—her spirit, to use, for the sake of that word—is her spirit in a less active state from when her brain was alive?

Prabhupāda: Spirit is always active.

Richard: It's always active at the same level?

Prabhupāda: Not same level, because you are understanding the spirit through the body. So body is changing. Just like the soul, when he's in the boy's body, it is talking so many nonsense things, but you don't take it seriously. But when you are grown up, if you talk such nonsense things, then you'll be taken as a nonsense, because the body has changed.

Richard: Okay, what I was leading up to was, her brain is dead, she has no . . .

Prabhupāda: Not dead; it is not working.

Richard: It's not working, okay. It's not working. She's getting no sensory input. She's not aware of the physical surroundings, and yet you maintain that her soul is still alive and still very active. Now would her state, her physical state, enhance the soul's activity or detract from . . .?

Prabhupāda: It has nothing to do with it.

Richard: It has nothing to do with it. Okay. Would it matter to you whether they did turn off her life-supporting apparatus? Would that make any difference?

Prabhupāda: What is that?

Rāmeśvara: No, it wouldn't.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: There are machines that are maintaining her life.

Rāmeśvara: Just like a person in a car, the car engine may fail and the person may get out of the car or he may linger in the car. The car is just a machine. So the soul is lingering in her body, even though it is . . .

Richard: But it's still very active.

Rāmeśvara: Yes, just like if my car breaks down, that does not mean I have broken down. I'm the passenger.

Richard: Can she be in touch with her soul in a coma?

Hari-śauri: She is soul.

Devotee: She is soul.

Hari-śauri: That personality, that's the soul.

Rāmeśvara: No, when the machine, when the conscious, when the body is broken like that, she cannot become self-realized.

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: She's active on the mental platform.

Prabhupāda: She's covered with the body, but she's different from the body. Just like you are covered by your dress, but you are different from the dress.

Richard: Okay.

Rāmeśvara: Thank you, Śrīla Prabhupāda.

Prabhupāda: Hare Kṛṣṇa.

Richard: Thank you.

Prabhupāda: Jaya. You are very intelligent boy. (laughs)

Richard: I don't know what good that does me.

Prabhupāda: They are good questions.

Rāmeśvara: You are very merciful, Śrīla Prabhupāda.

Richard: You are very patient, I'll tell you. (laughs)

Rāmeśvara: Thank you, Prabhupāda.

Prabhupāda: Hare Kṛṣṇa.

Richard: Thank you.

(break)

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: . . . he says even they don't associate temple this and that.

Hari-śauri: That boy has some intelligence, it's just, er, (laughs) he has to be guided a little bit. Too conditioned.

Prabhupāda: Guidance required. Tad vijñānārthaṁ sa gurum evābhigacchet (MU 1.2.12). (end)

- 1976 - Conversations

- 1976 - Lectures and Conversations

- 1976 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- 1976-06 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- Conversations - USA

- Conversations - USA, Los Angeles

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - USA

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - USA, Los Angeles

- Conversations with Media

- 1976 - New Audio - Released in November 2013

- Audio Files 60.01 to 90.00 Minutes