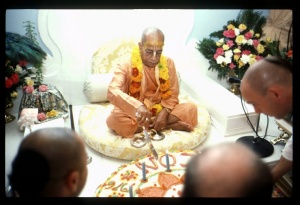

751005 - Lecture SB 01.02.06 - Mauritius

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

Prabhupāda:

- sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmo

- yato bhaktir adhokṣaje

- ahaituky apratihatā

- yayātmā suprasīdati

- (SB 1.2.6)

This is a verse from Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, First Canto, Chapter Two, text number six. There was a big meeting of great sages, saintly person, about 2,500 years ago at Naimiṣāraṇya. Naimiṣāraṇya still . . . those who have gone to India, they know, near Lucknow there is a place, it is called now, railway station, Nimsar, there is Naimiṣāraṇya. So there in the meeting the questions were put by the sages that to summarize the whole range of revealed scriptures, because in India the Vedic literatures are many-folded. First of all there are the four Vedas—Sāma, Yajur, Ṛg, Atharva. Then they are explained or supplemented by the Purāṇas, eighteen Purāṇas. Then they are further explained by 108 Upaniṣads. Then they are summarized in Vedānta-sūtra, Brahma-sūtra. And then again, the Brahma-sūtra is explained by Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. Bhāṣyāyāṁ brahma-sūtrāṇām. The Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam is the direct commentary by the author himself. Therefore you will find at the end of each chapter of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, śrīmad-bhāgavate mahā-purāṇe brahma-sūtra bhāṣye. Bhāṣya means commentary. Commentary means to explain. Just like in the Brahma-sūtra the first aphorism is athāto brahma jijñāsā: "This human form of life is meant for inquiring about the Absolute Truth." Brahman means Absolute Truth, the Supreme Truth.

So it is said that the human life should not be spoiled or expended like animals. Nāyaṁ deho deha-bhājāṁ nṛloke kaṣṭān kāmān arhate viḍ-bhujāṁ ye (SB 5.5.1). What is the distinction between the human form of life and the life of the hogs and dogs? What is the difference? The difference is that the hogs and dogs . . . (children shouting outside) (aside) It is not possible to stop them? We'll find the hogs and dogs, whole day they are searching after eatables, "Where there is some food? Where there is some food?" That is hogs' and dogs' life, the condemned life. They cannot have any peaceful life. They cannot do any intelligent work. They cannot produce food from the earth. They have no intelligence. The same earth is there, the dogs and hogs are there, the human being is also there, but human being has developed a civilization, comfortable life, the hogs and dogs, they cannot do that. Although they have got the same opportunity, but they cannot do it. So human life is meant for living very comfortably, brain clear to understand what is Absolute Truth, what is our life, what is the goal of life. Because the hogs and dogs, they will also die and we will also die, but we can understand what is the goal of life—the dogs and hogs, they do not know what is the goal of life.

Therefore in the Vedānta-sūtra the first aphorism is advised that human form of life . . . it doesn't matter where that human form of life has happened. It doesn't matter. Either in America or in India or in Pakistan or anywhere, human life is human life. So their business is to inquire about the Absolute Truth. That is the injunction of the śāstra. Therefore we find a form of religion in the human society. It doesn't matter whether Christian society or Hindu society or Muslim society or any other society—because they are human being, there must be a type of religion. And what is that religion? Religion means to understand God. This is the sum and substance. Religion means to understand God. In the śāstra it is said, religion means . . . dharmaṁ tu sākṣād bhagavat-praṇītam (SB 6.3.19). Religion means the codes and the rules and regulation given by God. That is religion. This is the summary, short definition of religion. If somebody ask you, "What do you mean by 'religion'?" the immediate reply is there in the śāstra, dharmaṁ tu sākṣād bhagavat-praṇītam na vai vidur ṛṣayo nāpi devāḥ (SB 6.3.19): "The principles of religion is given by God. It is unknown to the human being or the demigods." That means except God, nobody can give you religion. Just like the law, state law. Law means the principles given by the state. You cannot manufacture law at your home. That is not law. Similarly, religion means the law given by God. Therefore we must know who is God and what kind of law He is giving to us. This is religion.

So from Bhagavad-gītā we understand Kṛṣṇa, or God, says, yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir bhavati bhārata, tadātmānaṁ sṛjāmy aham (BG 4.7): "When there is discrepancies in the matter of discharging religion, then I incarnate, I descend." Why?

- paritrāṇāya sādhūnāṁ

- vināśāya ca duṣkṛtām

- dharma-saṁsthāpanārthāya

- sambhavāmi yuge yuge

- (BG 4.8)

So religion is disturbed by duṣkṛtina, demons, and those who are saintly person, they execute religion. So paritrāṇāya sādhūnām. Sādhu means saintly person, devotee of God. They are sādhu. And asādhu, or demon, means persons who deny the authority of God. They are called demons. So two business—paritrāṇāya sādhūnāṁ vināśāya ca duskrtam: "To curtail the activities of the demons and to give protection to the saintly person, I descend." Dharma-saṁsthā . . . "And to establish dharma, the principles of religion." These are the three business for which Kṛṣṇa, or God, or God's representative—or, you say, God's son—they come. This is going on.

So what is religion, then? The religion is obedience to God. Just like law means obedience to the state, and one who obeys the laws of the state, he is good citizen; similarly, the laws given by God, one who obeys the law, he is religious or saintly person. So it doesn't matter what religion you are following. It doesn't matter. If you are actually obedient to the laws of God, then you are religious. It doesn't matter. So that is explained here: sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharma yato bhaktir adhokṣaje (SB 1.2.6). Adhokṣaje: beyond the sense perception. We have got different stages of knowledge: direct perception . . . pratyakṣa, parokṣa, aparokṣa, adhokṣaja, aprakṛta—these are five stages of knowledge: direction perception, knowledge received from others, then realization, then anubhūti, understanding what is the position of God and His situation. That is called aprakṛta. Aprakṛta means not within this material world but above that. Śaṅkarācārya, he has described, nārāyaṇaḥ paraḥ avyaktāt. Avyaktāt. This material world is manifested. And above this, there is the total stock of material energy. That is called avyakta. And beyond that, there is spiritual world. Nārāyaṇaḥ paraḥ avyaktāt. So we have to understand God, where He is situated. He is situated everyone, everywhere, but still, we cannot see.

In Kuntī's prayer she said that, "Kṛṣṇa, You are without and within also, but still, You cannot be recognized." Naṭo nāṭyadharo yathā (SB 1.8.19). Just like one person's father or relative is playing on the stage, still, he cannot recognize him, who is playing, so similarly, Kṛṣṇa or God's position is adhokṣaja. Adhokṣaja. Akṣaja. Akṣaja means direct perception. Akṣa means eyes. Sometimes we say, "Can you show me God?" This is called akṣaja. But He cannot be seen by these eyes; therefore His name is Adhokṣaja. Adhah-kṛtaḥ akṣajaṁ jñānam. You cannot see God by direct perception. You have to create your eyes, you have to create your senses, so that you can see God, you can touch God, you can talk with God, you can feel God's presence. Therefore His name is Adhokṣaja.

When sometimes God is described as impersonal, that does not mean that He has no personality. He has His personality, but He is not a person like us. He is not a person like us. That is called impersonal. Impersonal does not mean that He has no personality, but the experience of our person . . . personality, God is not like that. In the Vedas they are very nicely explained, paśyaty acakṣuḥ: "God sees, but He has no eyes." Śṛṇoty akarṇaḥ: "He has no ears, but He can hear." If He cannot hear, then what is the use of our offering prayer? He hears, but He does not hear like us. We cannot hear in a distant place, a few yards. But God, He is in His kingdom. Still, if you offer prayer He can hear. That is God. Śṛṇoty akarṇaḥ paśyaty acakṣuḥ (Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 3.18). He is seeing everything, every action of your activities, but that kind of eyes, seeing everything—not only of my activities; your activities, his activities, everyone's activities—we haven't got such eyes. Therefore, when He is spoken of that, "He has no eyes," that means He has no eyes like us. It is to be under . . . acakṣuḥ. He hasn't got eyes like this—I cannot see more than hundred feet—but He can see everywhere. Sarvataḥ pāṇi-pādas tat: "He has got His hands and legs everywhere." He has got His eyes everywhere. So therefore He is described here, adhokṣaja. Adhokṣaja. Adhokṣaja means beyond sense perception. And still, you have to become obedient.

Therefore it is said, sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharma (SB 1.2.6). Paro dharma and aparā dharma. There are two natures: parā and aparā. These things are very nicely explained in the Bhagavad-gītā. This material energy, five elements, eight elements, even we can see. . . we cannot see five elements properly. Five elements: bhūmir āpo analo vāyuḥ khaṁ mano buddhir ahaṅkāra (BG 7.4). We can see earth, we can see water, bhūmir āpo. We can see fire, analo. But we cannot see the air, but we can feel that the air is blowing. That is also sense perception. We can see . . . we can perceive. We cannot see what is that sky, but we know, "Here is sky—vacancy." Then we cannot see even mind. We cannot . . . I know that you have got mind, you know I have got my mind, but you cannot see where is my mind, I cannot see where is your mind. Bhūmir āpo analo vāyuḥ khaṁ mano buddhir eva ca, bhinnā prakṛti me aṣṭadhā (BG 7.4). These are different energies of God, and the whole material world is composed of these five gross elements and three subtle elements. This is called material world. And Kṛṣṇa says further, apareyam: "These material energies, they are inferior energy, aparā. Beyond that, there is a superior energy." Apareyam itas tu viddhi me prakṛtiṁ parām: "My dear Arjuna, these gross and subtle material elements, they are inferior energy. Beyond that, there is another, superior energy." What is that superior energy? Jīva-bhūtaḥ mahā-baho yayedaṁ dhāryate jagat (BG 7.5): "That is that living being." We are all living being. So we are superior energy. We are exploiting the material resources; therefore we are superior. We are molding the material energy to our satisfaction, so we belong to the superior energy.

So at the present moment we are engaged in the activities of material energy. Just like we are economist, nationalist, scientist and so on, so on. That means all our engagements are within this material energy, even psychologists, mental speculators, philosophers—all material energy. But that is not our superior engagement. The superior engagement is explained here, sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmo (SB 1.2.6). Superior engage means to remain engaged in devotional service of the Supreme Lord. Sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmo yato bhaktir adhokṣaje. Bhakti. Bhakti means devotional service. When we understand the Adhokṣaja, the Supreme, the Absolute Truth, then we understand our position. Our position is eternal servant of God. This is our position. But at the present moment, because we are not in the superior energy, in the activities of the superior energy, we are struggling hard with this material energy.

- mamaivāṁśo jīva-bhūtaḥ

- jīva-loke sanātanaḥ

- manaḥ-ṣaṣṭhānīndriyāṇi

- prakṛti-sthāni karṣati

- (BG 15.7)

The Lord says that, "These living entities, they are part and parcel of Me." Mamaiva aṁśa. Aṁśa means part and parcel. Just like this finger is the part and parcel of my body, so the finger's business is to carry out or to see the comforts of the body. I want to itch my nostril; immediately the finger is engaged. And if the fingers cannot help me, then it is diseased. Similarly, we are part and parcel of God. If we cannot help God, if we cannot assist God, if we cannot serve God, that is our diseased condition. That is our diseased condition.

So we are, at the present moment, we are not helping God, we are not assisting God, we are not serving God, so this is our diseased condition. So we have to get out of this diseased condition. That is called mukti. The mukti is explained in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, muktir hitvā anyathā rūpaṁ svarūpeṇa vyavasthitiḥ (SB 2.10.6). Mukti means when we give up our false engagements and we are engaged properly in our original constitutional position. That is called mukti. So this bhakti means mukti. Because bhakti means to be engaged in devotional service of the Supreme, therefore that is mukti. And bhakti begins after mukti. That is also explained in the Bhagavad-gītā:

- brahma-bhūtaḥ prasannātmā

- na śocati na kāṅkṣati

- samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu

- mad-bhaktiṁ labhate param

- (BG 18.54)

Brahma-bhūtaḥ. We are all Brahman. The Māyāvādī philosophers, they are very busy to realize his Brahman position. So we are Brahmans. That is a . . . because we are part and parcel of God. God is Para-brahman, so we are part and parcel of God. We are not Para-brahman, the Supreme Brahman, but we are Brahman. Ahaṁ brahmāsmi, this realization, "I am not this body," that is called brahma-bhūtaḥ. So brahma-bhūtaḥ, when you realize this, this is called knowledge, brahma-jñāna that, "I am not this body but I am spirit soul, part and parcel of God. My duty is to assist God, to serve God." That is called brahma-bhūtaḥ. Otherwise, being jīva-bhūtaḥ, we are engaged in this material world, struggling with the material energy. That is called jīva-bhūtaḥ. And brahma-bhūtaḥ means to realize that, "Why I am unnecessarily struggling with this material world? I do not belong to this material world. I am spirit soul. My business is spiritual." That is brahma-bhūtaḥ. And as soon as one understands this position, then prasannātmā, he becomes immediately happy, joyful.

Just like if you are doing something for which you have no necessity, and when you come to realize that, "I am unnecessarily wasting my time" in this way, naturally, you become joyful that, "Why I am wasting my time in this way?" that is brahma-bhūtaḥ stage. Brahma-bhūtaḥ prasannātmā. Prasannātmā means joyful stage, no more anxiety. We are full of anxiety on account of our material conception of life, unnecessarily. So many leaders came and gone. So long they were living, they were always concerned. In our country . . . just like Mahātmā Gandhi, he came, big leader. Or in other countries, Churchill came or Hitler came. So long they were living, they were always anxiety, full of anxiety, fighting with one another. Now they are not existing. What is the loss there? But unnecessarily they were busy, so "Without me, my country will be finished, and this will be vanquished." Unnecessarily.

So therefore we require to be brahma-bhūtaḥ, then prasannātmā. Then, because our only business is to see that, "I am happy. I have no anxiety . . ." That we are searching after, every one of us. So that anxietylessness is possible when we come to this stage:

- sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmo

- yato bhaktir adhokṣaje

- ahaituky apratihatā

- yayātmā suprasīdati

- (SB 1.2.6)

If you want actually peace, then you must be engaged in the service of the Lord. And before being engaged in the service of the Lord you should be qualified, brahma-bhūtaḥ prasannātmā (BG 18.54). Brahma-bhūtaḥ. As soon as you become brahma-bhūtaḥ, you are jolly. What is the symptom of jolliness? Na śocati na kāṅkṣati. Na śocati means "does not lament." We are always lamenting for the things which we have lost, and we are always hankering for things which we haven't got. This is our business. So long we do not get, we hanker. And when we get, then "How to keep it?" That is anxiety. And when it is lost, that is also anxiety. This is the material position. And when you come to the spiritual position there is no such thing—no more lamentation, no lamenting, no hankering. Brahma-bhūtaḥ prasannātmā na śocati na kāṅkṣati, samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu (BG 18.54).

At that time it is possible to see that everyone is equal, because he can see. He does not see "Here is American." He does not see "Here is Indian." He does not see "Here is a brahmin." He does not see "Here is a dog." He sees all living being part and parcel of God. That is called samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu. That equality is possible when you are brahma-bhūtaḥ. Samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu. Artificially you have opened this United Nation, but your conception is, "I am Indian," "I am American," "I am Hindu," "I am Muslim." So how it can be, there can be unity? It is not possible. That is not brahma-bhūtaḥ stage. That is prakṛta stage, identifying with this body. So long you identify with this body, then you are in the material conception of life. There is no question of spiritual understanding, there is no question of joyfulness, there is no question of freedom from lamentation and hankering, and there is no question of equality. It is all false show.

So therefore here is the explanation, sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmaḥ. Paro dharmaḥ. Here it does not say that, "Hindu religion is the best" or "Christian religion is the best" or "Muhammadan religion is the best." No. That religion is best which teaches the follower how to love God. Sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharma yato bhaktir adhokṣaje (SB 1.2.6). If one is lover of God, then he is lover of everyone, because he knows everyone is part and parcel of God. If you love your father, then you love your brother. But if you do not know who is your father, then how you can say: "Universal brotherhood"? This is all hypocrisy. You first of all know . . . you must first of all know what you are, what is God, what is your relationship with God. And when it is perfectly understood, then there is the possibility of samaḥ sarveṣu bhūteṣu, paṇḍitāḥ sama-darśinaḥ.

- vidyā-vinaya-sampanne

- brāhmaṇe gavi hastini

- śuni caiva śva-pāke ca

- paṇḍitāḥ sama-darśinaḥ

- (BG 5.18)

Paṇḍitāḥ, one who is actually learned, he sees everyone on the equal level. Who are they? Vidyā-vinaya-sampanne brāhmaṇe. A brāhmaṇa who is very learned and very gentle, vidyā-vinaya . . . education means one is very gentle and learned. Vidyā-vinaya sampanne brāhmaṇe gavi, a cow; hastini, an elephant; śunice, a dog; śva-pāke, a dog-eater, caṇḍāla. He sees that they are . . . (break)

Indian man (1): He is everywhere. He is omnipresent.

Prabhupāda: Yes. He is present within your heart, but still, He has got His own place.

Indian man (1): This is why He says He has been . . . (indistinct)

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Indian man (1): But it can also mean that He is not everywhere, because . . . (indistinct)

Prabhupāda: Why not? That is God. That is God. You are thinking in your terms. Because when you are at your home you are not everywhere, you think God is like that. That is your deficiency. Why do you compare yourself with God? That is your deficiency.

Indian man (2): This is a philosophical point of view.

Prabhupāda: Not philosophical point, view. You are thinking God in your own terms. Because you are imperfect—when you sit in your home you cannot be present at my home—therefore you are thinking God is like that.

Indian man (1): When you say: "He descends," does it mean . . . (indistinct) . . .?

Prabhupāda: Yes. "He descends," it does not mean that He is absent in His abode. That is God. Advaitam acyutam anādim ananta-rūpam (Bs. 5.33). You understand this? Ananta-rūpam. He can expand Himself in unlimited forms. Otherwise, how it is possible, īśvaraḥ sarva-bhūtānāṁ hṛd-deśe 'rjuna tiṣṭhati (BG 18.61)? God is situated in everyone's heart. "Everyone" means within your heart, within my heart, within cat's heart, within dog's heart—everyone's heart. So there are innumerable living entities. How He is situated everywhere? Aṇḍāntara-stha-paramāṇu-cayāntara-stham (Bs. 5.35): "He is within this universe and He is within the atom." That is God.

Indian man (3): Swāmījī?

Prabhupāda: Yes?

Indian man (3): You are accepting to reply questions put by a young man. Will you still kindly answer all questions put by an old man? (laughter)

Prabhupāda: Hmm? What is that?

Brahmānanda: He says that—excuse me—that you have already accepted one question from a young man, so now would you kindly accept a question from an old man?

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes. You are neither old; he is neither young. (laughter) Paṇḍitāḥ sama-darśinaḥ (BG 5.18). Yes. Yes?

Indian man (3): In your lecture, Swāmījī, if I don't mistake, you have mentioned many authorities, beginning with the Veda, Brahma-sūtra, Bhagavad-gītā or wisdom of the Mahābhārata. Do you accept all truth?

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes.

Indian man (3): Or are they stories?

Prabhupāda: Yes. Because it is given by Vyāsadeva, therefore it is also authority.

Indian man (3): We have all listened to you very attentively.

Prabhupāda: Rāmāyaṇa, Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, that is also authority.

Indian man (3): We have listened to you very attentively, and I have no doubt that the audience have learned much which is . . . could be practiced to help us in some way to realize what we are and to realize God. Now, if God Himself comes to teach to someone in this world, and if he has learned from God directly and he is satisfied that he has learned, that he has understood, can he, a few minutes afterwards, forget that he has received instruction from God, and can he depart in a very ridiculous way from God, from what God has taught him in person?

Prabhupāda: Ridiculous way? What is that "ridiculous"?

Indian man (3): If I have read . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no. First of all correct yourself. What is that, "Ridiculous way"?

Indian man (3): If after receiving good education you act contrary to that education.

Prabhupāda: What is that?

Indian man (3): At least, it is ridiculous.

Brahmānanda: If you receive a good education and then you act contrary to that education.

Prabhupāda: If one has received good education, he cannot act contradictory.

Indian man (3): That is . . . I agree with you. But this is what, if I have understood . . .

Prabhupāda: So a person who has got real education, he cannot be ridiculous. No, why you are saying that?

Indian man (3): It can be explained by ridiculous.

Prabhupāda: No, no. Don't say anything which is contradictory. Education does not mean ridiculous. That means he is not educated.

Indian man (3): I have not said that education is ridiculous. I said that one who has got good education from a teacher . . .

Prabhupāda: So he cannot act ridiculously. If he acts ridiculously, then he has not good education.

Indian man (3): So if I have well understood . . .

Prabhupāda: You have not well understood. You say a person who has got education, still, he acts ridiculously. That means you have no knowledge what is education.

Indian man (3): I shall explain myself well, but if you wish to be . . .

Prabhupāda: So if you cannot explain yourself, how can I continue to hear you?

Indian man (3): If you have got one minute more patience, I will explain how.

Prabhupāda: No, no, no. If you speak ridiculously, how can I hear you? You say that one man has got education and he acts ridiculously. This is . . . your statement is ridiculous.

Indian man (3): I said if a man who has had good education . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no. He has no good education. You cannot say that. If he acts ridiculously, that, he has no good education.

Indian man (3): Well, let me put it another way. In the Bhagavad-gītā is there a passage, is there a chapter where Arjuna says: "I have heard all Your teachings. Now I have understood the truth," or not?

Prabhupāda: So you have to hear and you have to understand; then you can speak. Otherwise you will speak ridiculously.

Indian man (3): No. Arjuna has said that he has heard God Himself speak to him, and that he has understood the truth and that we are all, as you have said, a little bit of a finger in a body, and the finger must serve the body . . .

Prabhupāda: So you have to approach such person who has heard God, just like Arjuna.

Indian man (3): The next day he goes on the battlefield and he hears that his son has been killed. He loses all his self-control and he said: "I am going to throw myself in the fire. I have lost my son." Is that the action of a man who has heard God Himself speak to him? This is what I want to ask.

Prabhupāda: You mean to say Arjuna? What is your statement? You mean to say Arjuna?

Indian man (3): Yes.

Prabhupāda: So Arjuna, he . . . of course, sentiment . . . just like theoretically we understand, na hanyate hanyamāne śarīre (BG 2.20). Still, when my son dies I becomes affected. That is temporary. That is temporary. But Arjuna, after hearing Bhagavad-gītā, Kṛṣṇa gave him the liberty that, "Now I have spoken to you everything. Now whatever you like, you can do." What did he answer? He answered, kariṣye vacanaṁ tava. 'Yes, I shall carry out Your order." This is the conclusion, that temporarily you may be disturbed, under certain circumstances, but if your conviction is that, "I shall act according to the order of God," that is final. That is final. He did not act against the will of the Lord. That is his victory. Temporarily he might have been disturbed when his son was killed. That is different thing. Everyone becomes. But that does not mean he stopped work. That is wanted. What was the final conclusion? He did not leave the war field because his son Abhimanyu was killed, therefore he left—"No, I don't want to fight." No, he did not do that. He was affected for the time being. That is natural. But finally he concluded and he said: "Yes," kariṣye vacanaṁ tava (BG 18.73). Naṣṭo mohaḥ smṛtir labdhā: "My illusion is now over. I shall fight." That is right conclusion.

Indian man (3): Thank you.

Indian man (4): Swāmījī, may I ask, just to . . . as my friend has just said about the teaching of . . . in the battlefield, Śrī Kṛṣṇa, about the verse about . . . yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir bhavati bhārata (BG 4.7). It is an oft-repeated phrase or śloka which has gone deep into the subconscious mind of the Ind . . . especially the Hindu people have taken it, probably because of the all of the wrong interpretations, that why should we go and tire ourself or make effort? If we are in trouble, let us wait for the God to come down to the earth, and He will help us and do what we need or defend us.

Prabhupāda: That is your instruction. That is not God's instruction.

Indian man (4): But it has been.

Prabhupāda: No.

Indian man (4): According to my . . .

Prabhupāda: The God says that, "Here is injustice, so you should fight." God says that. God never says that, "I am God, Kṛṣṇa. I am your friend. You sit down idly and I shall do everything." He never said that. He said that, "You must fight." That is our duty. Not that God has given us hands and legs and you sit down idly and let God do it. This is not devotion.

Indian man (4): Then you agree with me that this oft-repeated śloka has created a state of fatalism among the Hindu community?

Prabhupāda: What is that?

Indian man (4): That yadā yadā hi . . .

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Fatalism. This verse created fatalism, fatalism, a sense of hopelessness.

Prabhupāda: Hopelessness?

Puṣṭa Kṛṣṇa: Pessimism. Fatalism.

Brahmānanda: It has been interpreted that this verse means that God will come, and therefore we don't have to do anything.

Prabhupāda: God is always present. You carry out the order of God. God is always present. You carry out the order of the Lord.

Indian man (4): The verse is clear, yadā yadā hi dharmasya (BG 4.7).

Prabhupāda: Yes. So that is being done every moment. Every moment we are forgetting our dharma and God is giving us instruction.

Indian man (4): Well, there is a state of . . . this state of fatalism which is prevalent in India and among . . .

Prabhupāda: It is not spoken to India. It is spoken to everyone. India, why do you bring "India"? God is not made for India.

Indian man (4): But I have nothing in India, but I know India, so . . .

Prabhupāda: Then why you say India.

Indian man (4): I have seen India. I know India.

Prabhupāda: No, why you bring India at all? God is not meant for India.

Indian man (4): But Hinduism . . . let us say Hinduism.

Prabhupāda: No no, God is not meant for Hindu.

Indian man (4): No, I am not talking about . . . I was talking about . . . (laughter) . . . that this śloka, I mean, probably . . .

Prabhupāda: That God said, yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir . . . (BG 4.7). He doesn't say, yadā yadā Hindu dharmasya glānir. (laughter) So why do you speak nonsense? He never says. Why do you speak like that?

Indian man (4): It has written. I mean it was read like that.

Prabhupāda: No, no. That is your creation. That is your creation, mental speculation. He never said yadā yadā hi Hindu dharmasya glānir bhavati. He never said. Why do you speak all these things?

Indian man (4): Anyway, it has created a state of fatalism.

Indian man (3): Yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir bhavati (BG 4.7).

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Indian man (3): "When there is unrighteousness, I come in this world to reinstate dharma."

Prabhupāda: Yes. That is the . . .

Indian man (3): And He has not come now. There is no unrighteousness in this world?

Prabhupāda: He has come, but you have no eyes to see. You require the eyes to see.

Scottish man: Sir, I have listened to your talk with very great interest. You're very clear and very lucid. But you're also very dogmatic, I feel. Is there any area of doubt in your own philosophy, or are you quite certain in every field?

Prabhupāda: What is that dogmatic?

Scottish man: Dogmatic? You are very . . . when you have a question put to you, you are very clear what the answer shall be. (devotees chuckle) Have you any doubts yourself that have not appeared to us?

Prabhupāda: So you answer. You are American?

Scottish man: I am Scottish.

Prabhupāda: Scottish, England. In Scotland we have got also. Edinburgh, we have got our temple.

Scottish man: But you are very . . . you seem very . . . your philosophy seems very clear-cut.

Prabhupāda: Thank you very much. (laughter)

Scottish man: Are you well satisfied with that, that there is no area of doubt?

Prabhupāda: Therefore it is appealing more to the Western countries. Yes. Mostly it is very acceptable in the Western countries.

Scottish man: Thank you.

Prabhupāda: So chant Hare Kṛṣṇa again. (end)

- 1975 - Lectures

- 1975 - Lectures and Conversations

- 1975 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- 1975-10 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- Lectures - Africa

- Lectures - Africa, Mauritius

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Africa

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Africa, Mauritius

- Lectures - Srimad-Bhagavatam

- SB Lectures - Canto 01

- Audio Files 45.01 to 60.00 Minutes