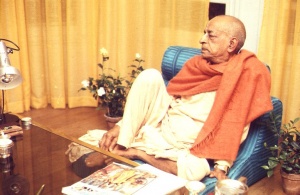

730710 - Conversation - London

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

(conversation with Mr. Wadell - boy school teacher)

Prabhupāda: There is a word in Greek dictionary, Kristo.

Mr. Wadell: Kristo . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Mr. Wadell: Well, yes.

Prabhupāda: Kristo.

Mr. Wadell: "The anointed."

Prabhupāda: "Anointed," yes.

Mr. Wadell: I understand.

Prabhupāda: So in India, ordinary men, they call Kṛṣṇa "Kristo." My younger brother, his name was Kṛṣṇa. But we are calling him "Kristo." That is ordinary use. So this Kristo word came from India. What is your opinion?

Mr. Wadell: I'm sorry. Can you . . .? Are you asking me?

Prabhupāda: Yes, Kristo.

Mr. Wadell: Kristo.

Prabhupāda: This is called apabhraṁśa. Apa means perverted, perverted spelling of Kṛṣṇa.

Mr. Wadell: I do not know the true answer to that question, I'm afraid.

Prabhupāda: And the meaning, "anointed." What is the explanation of "anointed"?

Mr. Wadell: I am not sure whether this was a title applied to him by his disciples or whether it was a title which he himself explained to them. And it makes a difference, whether he regarded himself as being anointed . . . if so, he would have said this was by the . . . his father.

Prabhupāda: But Kristo is person.

Mr. Wadell: It is a name applied to . . .

Prabhupāda: It is a name, then it must be a person.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, that is true. But the name is not always the same as the thing it describes or the person it describes. My name, I have said, is spelled in English in a certain way. It could be pronounced Waddle, Wawdle or . . . you know what I mean.

Prabhupāda: No, I am just suggesting there is similarity and the meaning "anointed." And from Kristo, the word Christ has come.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, in English, that is quite true.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Now the Christ, what is the meaning of Christ?

Mr. Wadell: I, well, it is this, that he is the anointed.

Prabhupāda: No, Christ means love, something like that?

Mr. Wadell: It is connected, I suppose, with the word meaning grace, which is . . . there is another Greek word which is haris. But I am not a theologian. You know, I am not a brilliant man who understands all the meanings of the words in the Christian faith. But I think the word Christ means anointed, and that it may well be connected with another word which means grace or favor. But I don't think it is the same word.

Prabhupāda: My idea is that if we can connect this Kristo and Christ that, "love of Godhead," there is some meaning. Because we, our Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement, means we are teaching people how to love God. That is our . . .

Mr. Wadell: To love is very difficult, is it not? It is very difficult.

Prabhupāda: No, it is not difficult.

Mr. Wadell: Well, it is both difficult and not difficult.

Prabhupāda: No. Everything. There is a Bengali word, yanra karya tare saje, anya loke lati baje. Anything, if one is practiced to do, he can do it very easily. And for others, it is just like striking with a rod. Anya loke lati baje. Suppose if there is some difficulty in electricity, I do not know anything. It will be very, very difficult task for me. But anyone who knows, immediately he connects two wires, there is light. It is simply to know the art.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, I would say, with respect, it is easy to feel love for people. It is not always easy to put this love into practice. Sometimes to love, you may have to be hard, apparently hard, to a person if you wish to help them.

Prabhupāda: The thing is that we want to love people, we want to help them, but if we do not know the process . . . the same thing: love . . . (indistinct) . . . that's it. You should know the process how to love. So our process is, according to Vedic injunction that, yathā taror mūla-niṣecanena tṛpyanti tat-skandha-bhujopaśākhāḥ (SB 4.31.14). Just like if you pour water on the root of the tree, automatically the branches, the twigs, everything, watered. Prāṇopahārāc ca yatendriyāṇām. If you supply food to the stomach, the energy is distributed to the hands, legs, eyes and everywhere. This is the process. But if you take the food and separately push on in the eyes and the ears and the hands and the finger, it is useless.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes, I agree, but . . .

Prabhupāda: Similarly, if you try to pour water to each leaf of the tree, it will be simply waste of time. Similarly, God is the root of everything. Our Vedānta-sūtra says, janmādy asya yataḥ (SB 1.1.1): Absolute Truth, wherefrom everything has come. So if we love the root, God, then we can love others. Otherwise not possible. Otherwise it is simply waste of time. They have tried. The so-called humanitarian work they have tried—unity and fraternity and so on, big, big words. But it has not come to . . . because there is no love of Godhead, it has failed. Even the United Nation. Central point is missing.

So our Vedic injunction is that sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmo yato bhaktir adhokṣaje (SB 1.2.6): "That system of religion is perfect which teaches how to love God." It doesn't matter, Christian religion, Hindu religion, Muhammadan religion. It doesn't matter. But God minus, this is the present position. Everyone wants to make minus God everything. This is going on. They have no clear idea. If I want to love you, I must have a clear idea of you. On vague idea, I cannot love. But they have no clear idea what is God. So how they can love God? And because they have failed to love God, all the so-called love—humanitarian, philanthropic works and, you know—they have become useless.

Mr. Wadell: Yes. The problem is a very big one. We are, perhaps, sent into this earth to know or to learn how to love.

Prabhupāda: No. I have got some objection. You cannot begin any scientific statement with the word "perhaps." We don't accept. You must be assured. You must be assured.

Mr. Wadell: I am merely saying . . . I do not wish to be presumptuous, if you understand me.

Prabhupāda: Well, as soon as you say "perhaps," "maybe," that is not . . . this has no meaning. Because it is not certain. You have no clear idea.

Mr. Wadell: But are there not things about which in the mortal life one can have no clear idea?

Prabhupāda: But if there is clear idea, why they should not take it? Why they should speculate "perhaps," "maybe"?

Mr. Wadell: But there are many things about which I cannot have any clear idea. I cannot . . .

Prabhupāda: No, you cannot have, but if you get clear idea, why you do not take it?

Mr. Wadell: No, I mean even in the physical realm. I cannot at this moment conceive what it is like, say, to be in Sydney, in many cities in the world. There are many things, many bits of knowledge which I cannot have. I cannot be everywhere at once. I am here now. I do not even know what is happening in the place from which I have come.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Mr. Wadell: And I must accept that. It is a . . . I cannot be certain about that. Would you not agree?

Prabhupāda: But if there is a process . . . suppose you are not in Sydney, but if there is a radio message from Sydney, how do you accept it?

Mr. Wadell: Oh, well, I'd believe it.

Prabhupāda: Then that is a question of belief.

Mr. Wadell: But that is not . . . belief is not quite the same thing as . . .

Prabhupāda: No, that is not belief; that is fact. Suppose a radio message is coming from Sydney, we accept it—fact—although I am not in Sydney. So it is a question of process, how to receive the message. If the process is perfect, then the message is perfect.

Mr. Wadell: But one has to believe the process is perfect as well.

Prabhupāda: Yes, if the process is perfect, one has to believe, one has to believe. Just like I will give you one example: Nobody knows who is his father, neither it is possible to know one's father by speculation. But there is a process. If you ask your mother, and if she: "This gentleman is your father," you accept the process and you get the perfect knowledge.

Mr. Wadell: One could look like one's brother. (laughs)

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Mr. Wadell: One could look very like one's brother.

Prabhupāda: What? I do not follow. What is . . .?

Mr. Wadell: You do not understand.

Śyāmasundara: Say it again.

Mr. Wadell: I have a brother . . .

Prabhupāda: Brother, yes.

Mr. Wadell: . . . who is very like me, and, well, this helps me to believe that I know who my father was.

Prabhupāda: No.

Mr. Wadell: In one sense.

Prabhupāda: That is another thing. Because one gentleman resembles your features, you think that he is your brother, that is another thing. But here the process that if you want to know who is your father, the process is that it should be known through the mother. There is no other process. It is not that suggestion: because somebody resembles my face, he is my father. Not like that. It is the perfect process.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes, I'm not . . . I agree with what you say. I am just adding another explanation.

Prabhupāda: Yes. And you cannot understand your father by any other process. This is the only process. That means things which are unknown, beyond our conception, you have to know it through the authority, just like you know your father through the authority of your mother.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes, I agree. But . . .

Prabhupāda: But you cannot say that things which are beyond our imagination cannot be known. You cannot say that. Can be known—provided you have got the real process.

Mr. Wadell: I'm afraid I must make, so far as I am concerned, a clear division between what I know and what I believe. There are certain things . . . it is maybe, partly a use of words, but whereas I know that I am here and that I have people in . . . I am in the same room with other men . . .

Prabhupāda: Do you think that this process, as I have suggested, to know one's father through the authority of the mother is not perfect?

Mr. Wadell: Oh, well, I think it's as near perfect as you can get.

Prabhupāda: Why you say: "As near"? Why still doubt?

Mr. Wadell: Because it is not quite the same thing as my knowing that I am here. There's a famous French philosopher who began all his philosophy from the phrase, "I am conscious; therefore I know that I exist." And he deduced everything, you know, starting from here.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That's a fact. You are conscious, I am conscious, that's a fact. It is not the question of belief. It is not question of belief. Belief may be wrong, but fact is fact.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, agreed.

Prabhupāda: So when one's . . . I say that I am conscious, you say you are conscious. We are conscious. That's a fact. And that consciousness is the symptom of the presence of the soul. Because from the dead body . . . dead body means when the soul departs from the body, there is no more consciousness.

Mr. Wadell: This is something on which I think I am probably too young or too . . . I have not thought enough about it to be able to tell you very clearly or to define very clearly what I think. This is very difficult, I know. But I am conscious that I do not know about this. I can make certain . . . I mean, I am inclined to accept what you say, but I cannot say that I know it.

Prabhupāda: Therefore when we are in doubts, therefore we have to refer to the authority. Just like when you are diseased, so you go to the physician, "What is the cause of my this trouble?"

Mr. Wadell: True.

Prabhupāda: Similarly, when you are in doubts, you have to approach an authority to clear the doubts. Otherwise you will remain in doubts, ignorance.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Therefore our Vedic injunction is, tad-vijñānārthaṁ sa gurum evābhigacchet (MU 1.2.12). Tad-vijñānārtham: in order to clear the doubt, to be in perfect knowledge, one must approach the authorized bona fide spiritual master.

Mr. Wadell: Can we go back to the physician? It is possible for a physician to be wrong.

Prabhupāda: Yes, we are always in wrong, because we are born ignorant. Everything is wrong because ignorant, foolish. Madman's conception. This is all wrong, childish. Therefore we send our boys, children, to school, to correct the wrong ideas.

Mr. Wadell: But some of the teachers may not be correct.

Prabhupāda: No. The process is you have to go to the teacher. But if the teacher is a cheater, then the whole thing is spoiled. A teacher must be teacher, perfect teacher. But if he happens to be a cheater, then the whole thing is spoiled.

Mr. Wadell: But the human situation is often a sort of mixture of the two. Sometimes . . .

Prabhupāda: No, mixture of two, that may be, but the process is that we have to approach the real teacher. Just like I approach the mother. Mother is supposed to be not cheater. But if the mother happens to be a cheater, then I am cheated. I am cheated. I don't get the information of my real father. But it is expected the mother should not cheat.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, oh, I know that it is expected of the teachers.

Prabhupāda: So it is my misfortune; if I get a cheater mother, then my whole life is spoiled.

Mr. Wadell: But the teacher may be wrong without wishing to be wrong.

Prabhupāda: No, he is not teacher. If a teacher is wrong, he is cheater. That is our proposition.

Mr. Wadell: Well, I'm sorry, this is a point which we must surely get right.

Prabhupāda: This is the real point. If you have to go to a teacher, you must go to a real teacher. You don't go to a cheater.

Mr. Wadell: But suppose I teach you something, a subject in which knowledge is not complete. There may be other discoveries.

Prabhupāda: Then you should not be teacher. Then you should not be teacher. Then you are cheater.

Mr. Wadell: But . . . no, because knowledge is . . .

Prabhupāda: That is, that is, that is our . . . teacher means . . . when I approach a teacher, he must be a bona fide teacher. He should not be cheater. If he has no sufficient knowledge, he should not pose himself as a teacher.

Mr. Wadell: Well, I am afraid I would be right out of court, 'cause you see I have often to confess to my pupils that I do not know.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That is going on, but that is not the system. If you do not know, you should not become a teacher. That is our proposition. (laughs)

Mr. Wadell: I see. Well, I am not at all sure that I could accept what you say. (laughs)

Prabhupāda: You must be sure that whatever knowledge you are giving, that is perfect. Then you are teacher.

Mr. Wadell: Well, you see, what you are . . . in that case, I should have to pretend, you see. I would have to pretend to know something which I do not know at all. Then I should be a cheater, wouldn't I? And that would be wrong. And there must be many things which I do not know.

Prabhupāda: Yes. It is better to become honest. If I do not know anything perfectly, I should not be teacher. That is right thing. And if I have got doubtful knowledge, "perhaps," "maybe," why shall I be teacher? I should, "No, no, I cannot teach. The subject is unknown." That is our process.

Mr. Wadell: Yes. I must say that I . . . there are many things of which I haven't got knowledge.

Prabhupāda: Yes, that is going on. That is going on. Therefore people are misled.

Mr. Wadell: No. I would mislead them more if I said that I knew.

Prabhupāda: No. No, no. If you do not know, why should you say you knew? That is another cheating.

Mr. Wadell: How do you mean?

Prabhupāda: When you know . . .

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes. I don't pretend. If I know something, I say I know, but . . .

Prabhupāda: Then you say that . . . you say: "I know."

Mr. Wadell: But when I do not know something, then I admit that I do not know it.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That admission, that's all right. But in that case, one should not take the post of the teacher. That is our Vedic injunction. One must know perfectly.

Mr. Wadell: You may well be right. (laughter) But actually, I think there are many things which . . . about which knowledge is changing. There are things . . .

Prabhupāda: That means cheating.

Mr. Wadell: I see you have here certain bits of equipment which didn't exist . . .

Prabhupāda: That is described in the Vedic literature: andhā yathāndhair upanīyamānāḥ (SB 7.5.31): "A blind man is trying to lead other blind men."

Mr. Wadell: I suspect that that is as probably very near to the truth of human situation . . . (laughs)

Prabhupāda: Yes. Andhā yathāndhair upanīyamānāḥ. What is the benefit? If I am blind, and if there are hundreds of blind men, "All right, come on, I shall . . ."

Mr. Wadell: I think we are all partially blind.

Prabhupāda: No, then there is no question of knowledge. Somebody must be with eyes. He can give knowledge. That is our proposition. As soon as you say blind, there must be somebody with eyes. It is a relative term. It is a relative term. You cannot say: "All are blind." Then there is no question of blind and with men eyes. As soon as you accept blind man, you must accept the other side, man with eyes.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, I see. You mean just as you distinguish from white, black, because it is different . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes, this is relative world.

Mr. Wadell: I agree, but I am using this in . . . as an example, not as an absolute description. I think my view—may I explain this—of the whole of which I am, as I say, I think, an imperfect part, a part which is trying to learn something which I am not even quite sure what it is that I am trying to learn . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no, this is . . . you are perfect gentleman, means that you say that, "I am imperfect." That is nice. But our point is that from imperfect man, imperfect knowledge is received. We cannot expect perfect knowledge from imperfect man.

Mr. Wadell: No. But where does your perfect knowledge come from, and how do you recognize it?

Prabhupāda: Yes, that is very important point, where to get the perfect knowledge. That is wanted. That is intelligence. Therefore the Vedas says, gurum eva abhigacchet (MU 1.2.12): "You go to a guru." "Guru" means heavy, who knows better than you, or who knows perfect. That is injunction.

Mr. Wadell: But, you see, this is . . .

Prabhupāda: We have to find out. We have to find out who can give the perfect knowledge.

Mr. Wadell: How do you know that you know? May I ask this? (laughter)

Prabhupāda: Yes, yes.

Mr. Wadell: This is the point which I would find, you know, without disrespect, this is something which is very difficult, whatever kind of faith you have.

Prabhupāda: It is not the question of faith. Faith may be wrong, belief may be wrong. That perfect knowledge can be received from the perfect source. So God is perfect. God is perfect. And one who follows the path of God, he is also perfect.

Mr. Wadell: But he is different from God, is he not?

Prabhupāda: May be. Just like . . .

Mr. Wadell: But this is important to me. Can, can . . .?

Prabhupāda: The same process. The mother gives the perfect knowledge, and the son receives the knowledge. So the knowledge received from the mother by the son is perfect. The son may not be perfect, but because he has received the knowledge from the mother, which is perfect, therefore he is perfect.

Mr. Wadell: In what respect do you consider yourself different from God?

Prabhupāda: Do you think I am also equal with God?

Mr. Wadell: If you . . . what I want to know is what you feel your relationship to God is.

Prabhupāda: My relationship is just like father and the son. The son is not different from the father; at the same time, he is different from the father.

Mr. Wadell: Yes . . .

Prabhupāda: The same relationship. We are all sons of God. Therefore, simultaneously, we are one and different. As son, the ingredient, the same. But He is father, we are son; we are different. This is called the philosophy of acintya-bhedābheda. Bheda means different, and abheda means one. So simultaneously one and different.

Mr. Wadell: May I ask you another question, which is, I have a mortal father . . .

Prabhupāda: Hmm? Mortal?

Mr. Wadell: Mortal father, a man, who you know, my parents, father and mother. Do you think that my father is in any way different in his parentage of me from God in His parentage of me?

Prabhupāda: No, everyone. Not only your father, your grandfather, your, or grandson—the same relationship: simultaneously one and different. Because we are spirit soul and God is the Supreme Soul. All the souls have come, emanated from Him. He is the Supreme Soul, and Paramātmā. The exact word used in the Vedic language, Paramātmā, Parabrahma, Parameśvara. This word param. Param means supreme.

Mr. Wadell: I accept that without any trouble. There's no . . .

Prabhupāda: The difference is God . . . in the Vedas it is stated that God is just like a person like you and me. Just like we are person, we are talking face to face, similarly, God is also a person. But . . . we are also persons. But what is the difference between the two classes of persons?

Mr. Wadell: Exactly.

Prabhupāda: Yes, the difference is eko yo bahūnāṁ vidadhāti kāmān (Kaṭha Upaniṣad 2.2.13). God is the maintainer, the supplier of all necessities of the so many persons. That is God.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, I accept that.

Prabhupāda: This is the difference. We are maintained, and He is maintainer. That is the difference. Otherwise, God is also person, I am also person. One is maintainer, and others, the plural number, they are maintained. In the Christian religion also, the same idea is: "God, give us our daily bread," maintenance. So that is the difference. He is the bread supplier, and we are bread eater. That's all.

Mr. Wadell: He doesn't supply His bread to everybody, unless . . .

Prabhupāda: Everybody. Yes, everybody. Beginning . . .

Mr. Wadell: People die, do they not?

Prabhupāda: Die, that is another thing. People die even if he has got many things to eat, still he dies. Can you check it? That does not depend on eating. There are many men, they are dying, although they are . . .

Mr. Wadell: I am taking you too literally. Let us forget about that point. It's not worthwhile.

Prabhupāda: No, no, because you say: "They are dying, God is not supplying," that is a mistaken idea. God is supplying. God is supplying. He is dying natural death. It is not that because there is want of supply, therefore he is dying. That is a mistaken idea. Death is not dependent on supply of food. There are so many other causes.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes, I agree about that, but you cannot . . . we have a phrase in our . . .

Prabhupāda: And death is inevitable. Even if you have sufficient to eat, you cannot avoid death. So death is inevitable. That is the problem of material life. Birth, death, old age and disease. So you cannot avoid it, so long you are materially existing. This can be avoided when you are spiritually elevated. That is our movement.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, you cannot live without . . . you do not, as we say, live by bread alone. And in that sense—it may be the sense in which you wish me to take—the sense, what you are saying, that God supplies bread, because bread could be both bread for the spirit, or soul . . .

Prabhupāda: No, bread is material. Bread is material. To maintain your material body, you require material bread. But spiritual body does not depend on material bread.

Mr. Wadell: Could we go back to the relationship between you, or all of us, and God? What my own experience has suggested to me is that the language which I use and the language which has been used by others to describe what we think Him to be is not really capable of accomplishing this very difficult task. It is an impossible task, in fact, because we are describing something which is so immeasurably greater, more difficult to understand fully. We can have a relationship, but I find it, the language which we use, is of . . .

Prabhupāda: Insufficient.

Mr. Wadell: . . . of mortal things, which are in our experience, and we apply those to something beyond the purely mortal realm. And sometimes the descriptions we use are to be taken only to a certain extent. They are useful as illustrations, but they are not to be taken as necessarily a fact. I think this has misled many people when they think about God, that we use a description, and it's rather like what we talked about to begin with, the question of names.

Prabhupāda: Question of?

Mr. Wadell: Names. Yes, I wrote my name for my friend here, and we joked as we came in about how this name should be pronounced. And, of course, it depends how people . . . how well people would know me, which name would apply to me. But I want to go one further than that, and I want to say that to know a name or a large number of facts and to be able to make a large number of statements about people is not the same as really knowing this person.

And this is our difficulty, as I see it, in relating ourselves to God, that although we make many statements about Him which are often picturesque ones . . . we say that He is almighty, that He can, in our religion, move mountains, or all sorts of separate statements like that. If you take all those statements together, they wouldn't really describe Him at all, not sufficiently.

Prabhupāda: Now, suppose one man is engineer. So if I address him, "Mr. Engineer," what is the wrong?

Mr. Wadell: Oh, there is nothing wrong, so long as you . . .

Prabhupāda: No, this particular name, when I give to him, what is the wrong?

Mr. Wadell: The only thing is that it is not complete.

Prabhupāda: Why not? That "engineer" word completes his situation. He is engineer.

Mr. Wadell: Well, you might say to me "teacher," but that would not be complete. That would not be a complete description of me.

Prabhupāda: No, it is complete.

Mr. Wadell: It is true, but it is not complete.

Prabhupāda: But when it is true, it is complete.

Mr. Wadell: I think it is . . . I don't think so. You see, I could . . . if I say: "This wall is white," that is a true statement, but it is not a complete statement. Because this wall is not like all white walls. There are many white walls which have not got curves in the corners or decoration at that particular point. Do you understand what I am trying to say?

Prabhupāda: But when . . . just like when we say God, "Kṛṣṇa," this word conveys the meaning "all-attractive." So what is the wrong? This Kṛṣṇa means all-attractive. So unless God is all-attractive, how He can remain God? It is not that God is for me God. God is for you also. God is for him also. Therefore He must be all-attractive. This is perfect . . .

Mr. Wadell: But not necessarily in the same way. Because just as we all have . . .

Prabhupāda: No. Just to understand what is God. If you try to understand in this way that, "God is good," "God is all-attractive," is it not perfect?

Mr. Wadell: It is a partial statement.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Mr. Wadell: But it doesn't tell me . . .

Prabhupāda: But then, when you go deep into the matter, you understand more and more. In the beginning . . .

Mr. Wadell: But you will never, I suspect, here on earth understand . . .

Prabhupāda: No, no, that suspicion I have already answered . . .

Mr. Wadell: (laughs) Not for me, you haven't.

Prabhupāda: . . . that you have to go through a process, right process. Then there will be no suspicion. The same example. But if you do not go through the process, you will be always suspicious.

Mr. Wadell: Yes. When I say "suspect," what I mean is not anything bad.

Prabhupāda: No, no, I know that.

Mr. Wadell: You understand that all I mean is that I am not sure about this. I think it may be true. I'm not sure.

Prabhupāda: So that suspicion will continue unless you take the right process.

Mr. Wadell: But there are . . . I do not think that this God gave me my mind, with my eyes and my sight, hearing, all these factors of the senses, and the intellect and the soul, if we are correctly speaking when we speak of it as something independently existing . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes, yes.

Mr. Wadell: He did not expect me, I'm sure, not . . . I'm sorry, to reject questions; i.e. my religion, and my . . . must be just as much a part of me as all that my intellect tells me. There must be no question which my religion cannot stand up to.

Prabhupāda: First of all you say that God has given you the intellect. He can withdraw it also.

Mr. Wadell: Well, we say not, because . . .

Prabhupāda: Why not? If He has given, He can withdraw also.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, I don't . . . well, we have a rather strange view of God, that . . .

Prabhupāda: No, you may have strange view. We are arguing. You see? As soon as you say God has given you intellect, He can withdraw also your intellect.

Mr. Wadell: But you see, what we have also to explain—why all men are not good. Now, if God were, chose, He could force all men to be good. But that is not the way.

Prabhupāda: No, God has given you intellect to become good, but because you disobey God, you have become bad.

Mr. Wadell: But if God is all-powerful and He cared to use His power . . .

Prabhupāda: No, He does not interfere with your little independence.

Mr. Wadell: Well this is exactly what I am . . . this is the point which you were trying to . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. Just like in the Bhagavad-gītā God says that, "You surrender unto Me." That means, "If you like, you surrender." God is not forcing, "You must." He is not forcing.

Mr. Wadell: Well, that's exactly what I meant. We are agreed. And . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. So that He does not do. Otherwise, otherwise, there is no meaning of being part and parcel of God. God is fully independent, and we are minute part of God. Therefore we have got independence. That independence is minute, but there is. So if God interferes with your independence, then you are no longer part and parcel of God. Therefore God says that, "You do this." Now, I misuse my independence, I do not do it. Therefore I am bad.

Mr. Wadell: Our positions do not differ on this point. We think exactly the same.

Prabhupāda: Yes. We do not do it. Just like your father says: "My dear son, do like this," but you disobey. Therefore you are bad son. So my badness is creation of my misuse of independence.

Mr. Wadell: Yes. But it may not be entirely willful.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Because God has given you the intelligence, and as I said, He can withdraw. Just like the same thing: The father says, "My dear son, do like this." But he is persisting in doing otherwise. (break)

Mr. Wadell: Yes, and for the same reason that He would not force, would therefore, for the same reason, not withdraw my intellect, having given it to me, I think.

Prabhupāda: Yes, that is stated, that is stated, that is stated. Just like I . . .

Mr. Wadell: You agree.

Prabhupāda: "Withdraw my intellect" means I have given you the intellect that, "You do like this," but you are persistent, doing otherwise, "All right, as you like, you do." This is withdrawal.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes, but one may be . . .

Prabhupāda: There is no force. There is no force.

Mr. Wadell: No, no. But what I want to go back to is the reason for disobedience. There are various possible ones. One may first not know what one is supposed to do. Secondly . . . is that all right? Do you agree about that?

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes. We do not know anything. We are to be considered all fools and rascals. That is our position. As soon as we come to this material world, accept a material body, we are all fools and rascals.

Mr. Wadell: Do you accept the whole of the material world? Do you think there are some things in it which are wrong?

Prabhupāda: Just like just as soon as you come to the prison house, you are all criminals. You may be very intelligent, but because you are in the prison house, you are criminal.

Mr. Wadell: I am . . .? Sorry.

Prabhupāda: Criminal.

Mr. Wadell: Criminal.

Prabhupāda: Because you are in the prison house, that is the proof that you are a criminal. You may be very intelligent man.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, yes. I'm not claiming . . . I haven't any claim to goodness. You must understand that.

Prabhupāda: Similarly, any living entity, any living entity who is originally part and parcel of God, God is all-good, therefore the part and parcel of God is also all-good. But as soon as comes to the material world.

(break) He . . . as far as one is put into the prison walls, within, he is a criminal. Now he has to undergo the criminal laws. Similarly, because we have come to this material world, we have to undergo the material tribulations. We cannot avoid.

Mr. Wadell: Well this is a very long . . . we are now on a topic on which I should have to require or ask, if I put it more politely, much more time than I have. Now, I am a person with responsibility to my boys. I must go now and say our prayers in the Christian way, which . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes, that's nice.

Mr. Wadell: . . . well, we profess up there, which not all believe, but some do, and they must be given their chance. (laughs)

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes, that is nice.

Mr. Wadell: Will you please, sir, excuse me at this moment? I would very much like to come back and pursue this.

Prabhupāda: Yes, you come often. Yes, you are welcome. Yes.

Mr. Wadell: If you feel it is of any interest or value to you.

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes, yes. After 4 o'clock you can come. You are welcome.

Śyāmasundara: Every night you can come after 4 p.m.

Mr. Wadell: Sorry?

Śyāmasundara: After 4 p.m., any night.

Mr. Wadell: Yes, well, we have a very busy week, because, as I say, we are correcting papers, we are ending our term.

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes, you must be busy.

Mr. Wadell: But what we are talking about is something which doesn't change today or tomorrow or yesterday. So when these things have been done, perhaps next week, I will come down.

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes. You are welcome. I want that responsible persons like you should try to understand the scientific value of this movement. It is not a sentimental movement. It is based on philosophy, science, authority.

Mr. Wadell: Well, it's on this question of authority, in a sense, that we would have the greatest difficulty. But another time, please.

Prabhupāda: Well, every religion is authority. That's a fact.

Mr. Wadell: It is, yes. That is true. But every individual is free and must find for themselves.

Prabhupāda: No, we, we . . . our proposition is, our proposition is that sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmo yato bhaktir adhokṣaje (SB 1.2.6): "That is first-class religion which teaches the followers how to love God." This is our proposal.

Mr. Wadell: Well, we shall see. We have a lot to . . . (laughs) It is quite possible that I, too, have been sent.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

(aside) Give him some prasāda.

Just wait little. Take prasādam. Our only fighting is against atheism, godlessness. This is our main fight.

Mr. Wadell: I agree.

Prabhupāda: Yes. People say: "There is no God. God is dead. This is all humbug." And so many there are, atheistic proposal. We are giving fight against this atheism.

Mr. Wadell: Will you excuse me. I must go.

Pradyumna: He's just bringing you a little . . .

Mukunda: We are just bringing you a little prasādam.

Mr. Wadell: Oh, no, no, I must. I have, my boys. They wait for me, and I must be with them. (laughter)

Prabhupāda: There is some prasādam.

Śyāmasundara: He is teacher just down the road in the school.

Prabhupāda: You take little this. Yes. Just take little.

Mr. Wadell: May I take just . . .

Prabhupāda: Just little. I am not giving you much.

(laughter)

Mr. Wadell: Oh, it's plenty. Just a little.

Prabhupāda: It is very good, tasteful.

Mr. Wadell: Thank you.

Prabhupāda: All right. (end)

- 1973 - Conversations

- 1973 - Lectures and Conversations

- 1973 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- 1973-07 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- Conversations - Europe

- Conversations - Europe, England - London

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Europe

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Europe, England - London

- Audio Files 45.01 to 60.00 Minutes