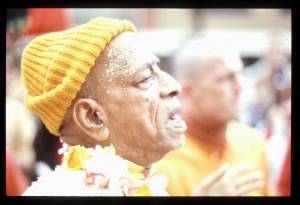

730426 - Morning Walk - Los Angeles

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

Devotee: (introducing recording) Prabhupāda's morning walk. Los Angeles, April 26, 1973.

Prabhupāda: . . . about animals not willing to die. Why? What is the psychology? Nobody wants to die.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They will ask, "How do I know that animals do not want to die?"

Prabhupāda: That is another foolishness. As soon as you want to kill, it cries. Man or animal, anyone. Even the trees, they feel pain. That is also . . . you do not know that?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They're conscious.

Prabhupāda: No. They feel pain. You know Jagadisha Bose's pulsitation . . .? What is called?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Pulsation?

Prabhupāda: The trees feel when you cut. They feel. There is machine. They . . . he discovered this. You have not been in Calcutta, Sir Jagadish Institute?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Probably not.

Prabhupāda: Yes. He, he discovered this wireless, Marconi's. Marconi's took advantage from him. They were talking together, and when Marconi got the hint from him, he immediately published. It was his invention, Sir Jagadish. Therefore he invented this pulsation of the trees, and started the Sir Jagadish Institution, Calcutta. So there is painful feeling even on the trees, what to speak of others.

Brahmānanda: Even a small insect . . .

Prabhupāda: Anyone.

Brahmānanda: . . . he'll run away so quickly, you try to go to him.

Prabhupāda: As soon you try to kill or attack, then he protests. And there is feeling also. Why? (japa)

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Because they want to enjoy the material world.

Prabhupāda: If you say so, then material enjoyment or enjoyment, material or spiritual, it doesn't matter . . .

Lady Passerby: Good morning.

Prabhupāda: (aside) Good morning. Thank you . . . (indistinct)

Then every living entity wants to enjoy. And that is the Vedānta-sūtra. Ānandamayo 'bhyāsāt (Vedānta-sūtra 1.1.12). Why they want to enjoy?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Because that is the eternal position of the living being entity.

Prabhupāda: His constitutional position is ānandamaya, joyfulness, but he does not get here that ānanda. He's seeking that ānanda, but it is being checked by condition. He cannot enjoy. There are so many impediments. Just like we want to walk, but there are so many impediments. We want to walk on the sea beach, but there are so many obstacles. So my position is that I want to enjoy, and nature's position is that she will check it. She'll not allow. Why? Why I am put into this condition? What do the scientists reply, rascals?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They don't have any answer.

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They don't have any answer, right answer.

Prabhupāda: That means they're rascals. They do not know.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: So our answer will be because of the laws of nature?

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Because we are under the laws of nature . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. But why . . .? I am against laws of nature. That is my question. If . . . if I am also nature's product, then why I against laws of nature? Why?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: By forgetting my real relationship, I tend to rule over the laws of material nature.

Prabhupāda: That I am struggling. That is my business here. I am simply struggling. Laws of nature is obstructing my process of enjoyment, and I want to enjoy. Why this position? We inquire these intelligent questions. What they are inquiring? They do not know what to inquire.

Brahmānanda: Yes.

Prabhupāda: Fools. Animals.

Brahmānanda: Sanātana Gosvāmī also asked that question to Caitanya Mahāprabhu . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes. That is, that is the question of human life that, "I want to enjoy. Why there is obstruction of my enjoyment?" Then the next question will be, "Then what I am, and what is this nature?" These are intelligent questions. That is called brahma-jijñāsā. "Where shall I eat?" "Where shall I sleep?" these are very minor questions. They are questions for animals. For the human being, this is the question that, "I want to enjoy life. Why there are so many obstruction?" This is human question.

The animal, they do not question. They submit. Just like when you slay one animal, it submits. But a human being, there is law, because human being is intelligent. So you cannot kill any other human being. You cannot murder. Then you'll be hanged. But they cannot make law. They're lower-grade animals. They submit, somebody killing. But the objection is there, both by the human being and the animal, that the "Why you are killing?" But he's helpless. The man has invented some means. So they have made their laws. But both of them are objecting.

In your, in America somewhere, when I first came, there was some incidence that in a live store, they got some opportunity to flee away. Then all the cows were fleeing away. And they were shot down. They were stopped. They knew that, "We are stocked here for being killed." So they got some opportunity, going away. And there is always miserable condition. Just like why you have covered so much? Why you have spent for covering? This is also miserable condition. Miserable condition. In some other place, they are . . .

Brahmānanda: It's too hot.

Prabhupāda: Too hot. Electric fan required. So we are always in miserable condition. We are trying to avoid these waves so that I may not be in miserable condition by wetting my shoes. So there is always struggle. Nature is trying to put me in miserable condition, and I am trying to save myself or to keep myself comfortable. This is called struggle for existence. They say that the world is imperfect. So they, do they not admit?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Yes.

Prabhupāda: So imperfect means it is not congenial for my joyful life. Therefore we are inventing something to become joyful.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: That is what scientists are trying.

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: That is . . .

Prabhupāda: That means you are struggling. That means you are in miserable condition. So why you are put into miserable condition? Why do they not ask this question? This is intelligence. You are submitting. You are trying to get out of the miserable condition, but you are unable. You are submitting. Therefore nature is very forceful. Daivī hy eṣā guṇamayī mama māyā duratyayā (BG 7.14). You cannot surpass. It is not possible. Then the next question will be, "How we can surpass?" That is real inquiry.

Brahmānanda: How . . .?

Prabhupāda: . . . we can surpass.

Brahmānanda: Oh, the misery.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Miserable conditions.

Prabhupāda: Miserable condition. So miserable condition is called māyā. The answer is in the Bhagavad-gītā, how we can surpass: mām eva ye prapadyante māyām etāṁ taranti te. Clear answer. "Anyone who surrenders unto Me, he can get out of this miserable condition offered by the māyā." They're eating; the wave came. Again trying. This is struggle for existence. Survival of the fittest. Who survives? Who is the living entity who has surpassed the tribulations of material nature? Where is the fit?

Darwin's theory: survival of the fittest. Who is that fit? Nobody's fit. Even the so-called scientists, they are also not fit. Professor Einstein, when there was death, he could not save. He must die. So nobody's fit. Where is the survival of the fittest? Simply struggle for existence. Survival of the fittest means Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Tyaktvā dehaṁ punar janma naiti mām eti kaunteya (BG 4.9). This is fittest.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They were talking about the temporary existence of the material body.

Prabhupāda: Eh? That is foolishness. That is foolishness. Just like if you go into the sea and if you want to be comfortable, this is foolishness. You cannot be. You are animal of land. If you are put into the water, however expert swimmer you may be, you'll not be comfortable. That's not possible. So you are spirit soul. You cannot be comfortable in the material world. You can struggle, but that is not possible. And they are simply giving bluff, "In future, we shall. In future." This is rascaldom. They don't admit that it is not possible.

They simply give bluff, "In future." You see? "In future, it will be," we can also accept that, provided you have taken the proper means. But where is your future if you are wrongly directed? A child's future is bright when we see that he's being educated, he's going to school. But he's in the . . . playing on the street, where is his future? He has no future. He's wasting his time.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: That is the favorite theory for the scientists.

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They like to do things in future.

Prabhupāda: That is nonsense. We say it is nonsense. In future, it is all right. You say: "In future . . .", but where is your method for future prosperity? That I am talking. If a child is getting proper education, then we can say that he has got a good future. But if the child is wrongly directed, where is his future? A patient who has gone to the physician and undergoing treatment, he can expect in future he will be cured. But if he's lying down on the bed and does not know who is physician, then where is his future? He has no future.

So all these leaders, they're rascals, and who are following these rascals, where is his future? He has no future. They're all rascals. Anyone accepting, "This rascal is a great scientist," so his future is doomed.

Brahmānanda: The blind leading the blind.

Prabhupāda: That's all. They do not . . . he does not know what is future happiness. He does not know.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They don't want to admit that.

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: They say they cannot do at the moment, but somebody will come up in future so they can show. But they don't want to admit . . .

Prabhupāda: So that's all right, but, at the present moment, you are rascal. Somebody when come, intelligent, that is another thing, but you are rascal. So why you are leading, cheating others? That is our protest, that you know that you are a rascal, and you are cheating others to become leader. That is our protest.

Why should you cheat others? Mūḍha. If he says that "How do you know I am rascal?" Because you do not know God. Therefore you rascal. Mūḍha. Na māṁ prapadyante mūḍhāḥ (BG 7.15). If you are . . . would have known what is God, then you would have surrendered to Him. Then you are intelligent. But because you do not surrender, you do not know what is God, therefore you are rascal. This is the definition of rascal. Jñānavān māṁ prapadyate. And intelligent means one who surrenders. He's intelligent. One who does not, he's rascal.

Brahmānanda: We have to expose these rascals.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That is our business.

(pause)

Na māṁ prapadyante mūḍhāḥ duṣkṛtino narādhama (BG 7.15). Always engaged in sinful activities. And because they are sinful, they have been given food by nature: "Eat dog. Eat the snail. Eat stool." Are these things eatables? And those who are intelligent, Kṛṣṇa conscious? For them, fruits, flowers, cāpāṭīs, nice things.

Brahmānanda: The swans and the crows.

Prabhupāda: Yes. The swans and the crows. So expose them as crows.

(pause)

Svarūpa Dāmodara: The leaders in our society, nowadays, seems that they forget their own present moment, but they're thinking for their children, future.

Prabhupāda: So how they are thinking? If he does not know, what is the use of thinking rascally? One can think properly if he knows things. If he does not know, then what is the use of thinking? The madman also thinks. What is the use of such thinking? Now our thinking begins from the Bhagavad-gītā. Kṛṣṇa says, dehino 'smin yathā dehe kaumāraṁ yauvanaṁ jarā, tathā dehāntara-prāptiḥ (BG 2.13): as the body's changing from childhood to boyhood, boyhood to youthhood, similarly the proprietor of the body will change this body at the last moment. Death means changing of the body. This is the . . .

Now we can think. When there is proper subject matter, then you can think: how it is, how the changes. You have no proper subject matter, nobody is to guide you, what is the value of your thinking? Like dogs and cats. You do not know how to think. That is possible. How to think, that is possible in human life. So if you don't take up opportunity how to think, then what is the use of your thinking like cats and dogs? Simply wasting time.

The valuable life, you are wasting. Making experiment in the laboratory, nonsensically, that from matter they'll create life. You see. How this nonsense . . .? What is the use of such thinking, which is never possible? These rascals are thinking on that, in that way, that they'll in future produce life from matter, which has never been possible in the history, past, present, and they're thinking, "Oh, bright future." That potter's thinking. Yes.

Brahmānanda: Actually, the future looks very dim because of the military. They've created such a military threat with their atomic bombs and armies and so on.

Prabhupāda: Hmm?

Brahmānanda: The future is very bad because of their military burden, atomic bombs. This is what the scientists have created. They're thinking a bright future, but actually the future is . . .

Prabhupāda: Very dark.

Brahmānanda: . . . seems very dark.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Idle brain is a devil's workshop. If they're not directed, then think like devil. We are thinking rightly because we are taking direction from Kṛṣṇa, the most perfect. Therefore our thinking has meaning. And what is the value of their thinking? It has no value. Now we are thinking . . . just like, take the first instruction, that within this body there is the proprietor of the body. You can go on thinking, "Then am I this body?"

So you can think on your finger, "I am this finger?" The answer from the within will come, "No, you are not finger. It is your finger. It is your finger. You are not finger." If I am finger, then if I cut my finger, why shall I not die, if I am finger? Therefore it is my finger. Just like I'll never think that I am this stick. It is my stick. That is thinking. That is thinking. If I wrongly think that I am this body, then your whole thinking process is wrong. And they are thinking like that, that we are this body.

- yasyātma-buddhiḥ kuṇape tri-dhātuke

- sva-dhīḥ kalatrādiṣu bhauma ijyadhīḥ

- yat-tīrtha-buddhiḥ salile na karhicij

- janeṣvabhijñeṣu sa eva gokaraḥ

- (SB 10.84.13)

So such kind of thinking is done by the asses and cows, yasyātma-buddhiḥ. One who is thinking, "I am this body," he's no better than the animal, ass or cow. They're all thinking like that, "I am this body." They're asses. And the whole world is suffering by thinking like that: "I am American," "I am Indian," "I am Russian," "I am this," "I am that." That's all. We must know how to think.

Then our thinking will produce some good result. If I do not know how to think, then what is the use of my thinking? A mad man is also thinking, "I am the emperor." Does it mean that he's emperor? Sometimes, I have seen, a madman falls flat on the street: "Nobody can check me." So motor driver, they become little cautious (chuckles)—"He's a rascal, madman."

So madman's thinking . . . what is the value of madman's thinking? They're all mad. Piśācī pāile jana mati-cchanna haya. They're a ghostly haunted person. As he's mad, similarly those who are entrapped by this material energy, they're all madmen. If I think that, "I am this coat. I am this shirt. I am this cloth," am I not mad? The body's just like shirt and coat. Vāsāṁsi jīrṇāni yathā vihāya (BG 2.22).

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Thinking is a natural process.

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Thinking is a natural process.

Prabhupāda: Yes. You have got mind. You have got mind. Therefore you must think. But that thinking . . . why there is psychology science? What do you think? Why you go to school, college to learn psychology? To learn how to think; how thinking process is going on. That is, education required, how to think correctly.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: So the subject matter of thinking . . .

Prabhupāda: The child is sent to school just for teaching him how to think correctly. Otherwise, what is the use of sending him to school? He can think at home. Why they are sent to school? To learn how to think. (japa)

(pause)

This is thinking, when you question that, "I want to become happy. Why I am not happy?" This is thinking. Everyone wants to become happy, but nature's process is to obstruct his happiness. So one should think, "Why this is position? I want to live. Why, by laws of nature, I am put to death? I must die? This is against my wish, against my desire." This is thinking.

So how to get out of it? This is real thinking. I don't want something, but something is forced upon me, and why it is so? When this "Why?" question will come to me, that is real thinking. Where is that thinking? These rascals, where is that thinking? How to check death, how to check disease, how to check old age—where is that thinking? Where is that scientist? Who is making research how to stop death?

Who is making research how to stop disease? You can manufacture medicine for the disease, but you cannot check happening of disease. That is not possible. Why it is? That is thinking. I want something, but it is being obstructed by nature. Why it is so? This "Why?" question must have come. Then his thinking is proper. That is Kena Upaniṣad. Kena.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Kena?

Prabhupāda: Kena Upaniṣad. This "Why?" Simply so many "why's". Harer nāma harer nāma . . . (CC Adi 17.21).

(pause)

After making so much research and invention, after all, the scientist's going to die like cats and dogs. Then what is the use of his thinking? The cats and dogs also will die, and Professor Einstein will also die. So where is the difference? Real unhappiness, neither the scientist can check, neither the cat and dog can check. So where is the use of your thinking foolishly? And they do not believe that there is life after death. So far we are concerned . . .

(break) Neither they do believe that there is life after death, although practically we are seeing: after child's life, there is youth's life; after youth's life, there is elderly life—after elderly life, there is old life . . . so this we are seeing. Still we do not believe that after this body there is life again. Natural sequence. Big, big professor, they say, "Oh, after this body, everything is finished." And they're planning all happiness on this basis. Harer nāma harer nāma . . . (CC Adi 17.21).

(pause)

Devotee: Any moment.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Yes.

Brahmānanda: It's a shaky platform.

Prabhupāda: Yes. All platforms shaky. At any moment, there is danger.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: The waves are much bigger this morning.

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: The waves are much bigger.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: This morning.

Prabhupāda: Bigger or smaller, it is always dangerous. Big fire or small fire, fire is fire; it will burn. That's all. In a . . . Cāṇakya Paṇḍita has given this example—this fire, debt and disease, never think big or small. They are always dangerous.

Brahmānanda: Fire . . .?

Prabhupāda: Fire, disease and debt. How he instructed us. If you take loan from somewhere, interest compounded, one day it will become so big, unmanageable by you. Similarly fire may be very . . . a spark, but gradually it will so increase, oh, blazing fire. Disease also. Now there is little pain. Now, if it increases, it becomes tuberculosis. So therefore he has said, "Never neglect these things: fire or . . . smaller or higher." They're always dangerous.

(pause)

There is a, in India, there is a proverb, hīrā and khīra. Hīra means diamond, and khīra means cucumber. It has no value, a few cents. And diamond is very valuable. But if some . . . somebody steals khīra, he's also criminal, and one body steals hīra, he's also criminal. The punishment is equal. If he says: "I have stolen one khīra. What is the value of it?" But by law, he's criminal. Never mind.

(pause)

Harer nāma, harer nāma . . . (greeting passerby) Jaya.

Passerby: Hare Kṛṣṇa. (break)

Prabhupāda: . . . that he'll be happy in that way.

Brahmānanda: Yeah.

Prabhupāda: What is the meaning of that such thinking, in such wretched condition? But he's thinking.

Brahmānanda: If we tell him to join us, he won't like it.

Prabhupāda: No, because he's thinking this is happiness.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: So the theory of relativity's everywhere.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That is a fact.

Brahmānanda: One man's meat is another man's poison.

Prabhupāda: Poison. Harer nāma, harer nāma . . .

(pause)

If Śyāmasundara has not started from London, you can ask him to bring my overcoat and . . .

Brahmānanda: Pullover.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

(pause)

Devotee: How does one practice to keep the mind from being restless?

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Devotee: How does one practice to keep the mind from being restless?

Prabhupāda: To have good association.

Devotee: Pardon me?

Prabhupāda: If you keep yourself with the rascals, then you'll think like rascals. And if you keep yourself with sane men, then you'll think like sane men. Association. That is required. That is the only way.

Devotee: And then . . . and then for detachment, it's just constant austeri . . .

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Devotee: For detachment, it's just austerities?

Prabhupāda: Detachment, when you will understand that, "This is good," "This is bad," naturally you'll have detachment for the bad. Unless you know, "This is good," "This is bad," how there can be detachment? When you are offered two kinds of foodstuff, and if you know, "This is good," "This is bad," then naturally you have detachment for the bad and pick up the good. First of all you have to know what is good and bad.

Then, when you are convinced, naturally you know, "Oh, this should not be taken." Detached, automatically. Paraṁ dṛṣṭvā nivartate (BG 2.59). Therefore knowledge is first required for detachment. Jñāna-vairāgya-yuktayā (SB 1.2.12). Jñāna, first of all knowledge, then detachment. Unless you have knowledge, artificial detachment will not work.

(pause)

Devotee: There are many that tell about knowledge for being good, but how do you really know? Is it just a feeling?

Prabhupāda: Hmm? Hmm? Knowledge means culture. Just like we were discussing. This is the process of knowledge: inquiry from right person and take the answer. That is knowledge. Just like a child takes knowledge from his father, "Father, what is this?" He gives knowledge. So you must inquire rightly from the right person. Then you get knowledge. This is the process of knowledge.

Brahmānanda: The child also has faith.

Prabhupāda: Eh?

Brahmānanda: The child also have faith in the father, that the father will give him the proper answer.

Prabhupāda: No, no. Faith or no faith. Child does not know that he has got faith, but naturally he's asking father. That is the natural source of knowledge. When you approach the right person, you may have faith or no faith, you get the right knowledge. It doesn't matter. Just like fire: if it is real fire, you touch it, it will act. You know or do not know, it doesn't matter.

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Just spontaneous.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

(pause)

Just like somebody says: "I have no faith in God." He may have faith or no faith. It doesn't matter. God is there. If somebody says: "I have no faith in death," does it mean that he'll not die? So faith is useless. Faith is created according to one's sense. It is not very essential. If there is something positive, you have faith in the negative, so it doesn't matter.

Brahmānanda: Doesn't negate it.

Prabhupāda: No. Fact is fact. Whether you believe or not believe, it doesn't matter. Hiraṇyakaśipu thought that, "I shall not die on the land, on the water, on the sky." But death was there. Asuric. This is asuric thinking.

(pause)

Svarūpa Dāmodara: It's called captivation by the illusory energy?

Prabhupāda: Hmm?

Svarūpa Dāmodara: The illusory . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes, yes. Ignorance.

(pause)

What is time?

Brahmānanda: Six-thirty-five.

(long pause)

Devotee: . . . (indistinct)

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Tar. Coal tar.

Prabhupāda: Something in . . .

Svarūpa Dāmodara: Oh, is it?

Devotee: Maybe . . . (indistinct)

Prabhupāda: They were still alive . . .

Devotee: . . . in a human form?

Prabhupāda: Yes, for Kṛṣṇa there is no such consideration, human form or plant form or . . . everyone is part and parcel of Kṛṣṇa. Why you are anxious to know about the human form? Why? Eh? What is your answer? Question? "Tulasī-devī should be in human form." Why you are asking this question?

Devotee: I was wondering is she was alive in human form while Kṛṣṇa was on earth.

Prabhupāda: No, no. She may not be. But where is the wrong if she's not in human form? Eh? Everyone is alive—plants, beasts. Everyone is alive. Why you are so much anxious of the human form of life?

Devotee: It wouldn't matter.

Prabhupāda: Kṛṣṇa can talk with animals, with trees, with plants. That is Kṛṣṇa. Do you think that "I cannot talk with plants; therefore the plant should be in human form"? That is your conception. Heh? If I can talk with everyone, then where is the difference for me, a human being or an insect or plant? So there is no such question that everyone should be in human form, then one can talk with Kṛṣṇa and enjoy. No.

(pause)

Devotees: All glories to Śrīla Prabhupāda. (obeisances)

(Prabhupāda enters car) (end)

- 1973 - Morning Walks

- 1973 - Lectures and Conversations

- 1973 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- 1973-04 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- Morning Walks - USA

- Morning Walks - USA, Los Angeles

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - USA

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - USA, Los Angeles

- 1973 - New Audio - Released in May 2015

- Audio Files 60.01 to 90.00 Minutes