730721 - Conversation - London: Difference between revisions

RasaRasika (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Pradyumna:" to "'''Pradyumna:'''") |

RasaRasika (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Revatīnandana:" to "'''Revatīnandana:'''") |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

According to ''Vedas'', there are four kinds of sinful activities: illicit sex, unnecessary killing of animals, intoxication and gambling. ''Yatra pāpaś catur-vidhaḥ.'' So God is purest. ''Paraṁ brahma paraṁ dhāma pavitraṁ paramaṁ bhavān'' ([[BG 10.12-13 (1972)|BG 10.12]]). How one can approach God if he leads a sinful life? That is our propagation. You give up this sinful life. Then you'll be able to understand God. You follow Christianity or Muhammadanism or Buddhism, it doesn't matter. You give up this sinful life. | According to ''Vedas'', there are four kinds of sinful activities: illicit sex, unnecessary killing of animals, intoxication and gambling. ''Yatra pāpaś catur-vidhaḥ.'' So God is purest. ''Paraṁ brahma paraṁ dhāma pavitraṁ paramaṁ bhavān'' ([[BG 10.12-13 (1972)|BG 10.12]]). How one can approach God if he leads a sinful life? That is our propagation. You give up this sinful life. Then you'll be able to understand God. You follow Christianity or Muhammadanism or Buddhism, it doesn't matter. You give up this sinful life. | ||

Revatīnandana: In the Bible it says: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God." | '''Revatīnandana:''' In the Bible it says: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God." | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes, yes. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes, yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: It's possible to see God, but only if there's purity of heart. And a sinful person has not got that purity of heart. | '''Revatīnandana:''' It's possible to see God, but only if there's purity of heart. And a sinful person has not got that purity of heart. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, I . . . some of the very simplest people have been nearer to God than those of great intellectual standing. That's true. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, I . . . some of the very simplest people have been nearer to God than those of great intellectual standing. That's true. | ||

Revatīnandana: Not "simple", sinful. Not simple. We're saying "sinful." | '''Revatīnandana:''' Not "simple", sinful. Not simple. We're saying "sinful." | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Sinful. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Sinful. | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Oh, sinful! I . . . I thought . . . I thought you said . . . sorry. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Oh, sinful! I . . . I thought . . . I thought you said . . . sorry. | ||

Revatīnandana: Yes, it's, it's, it's sin . . . I'm saying . . . even in the Bible it says: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God." | '''Revatīnandana:''' Yes, it's, it's, it's sin . . . I'm saying . . . even in the Bible it says: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God." | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: And how can a . . . how will a sinful person have that purity of heart? | '''Revatīnandana:''' And how can a . . . how will a sinful person have that purity of heart? | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: No, well, a sinful person hasn't got purity of heart. No, quite. | Sir Alistair Hardy: No, well, a sinful person hasn't got purity of heart. No, quite. | ||

Revatīnandana: Yes. | '''Revatīnandana:''' Yes. | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' So do you . . .? Don't you think that killing of animal is sinful activity? | '''Prabhupāda:''' So do you . . .? Don't you think that killing of animal is sinful activity? | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

Therefore every civilized society has got a type of religion to become purified so that he can understand God. Without being purified, how it is possible? That is not possible. So at least these things should be accepted as they are in the Bible, "Thou shall not kill. Thou shall not covet." Illicit sex life, intoxication, and killing of animals, these are in the Bible. Why they are not accepted? This is not our impositions. This is already there. | Therefore every civilized society has got a type of religion to become purified so that he can understand God. Without being purified, how it is possible? That is not possible. So at least these things should be accepted as they are in the Bible, "Thou shall not kill. Thou shall not covet." Illicit sex life, intoxication, and killing of animals, these are in the Bible. Why they are not accepted? This is not our impositions. This is already there. | ||

Revatīnandana: And in every scripture . . . | '''Revatīnandana:''' And in every scripture . . . | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: . . . for purification there are so many processes. | '''Revatīnandana:''' . . . for purification there are so many processes. | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' So how they can be God conscious without being purified? | '''Prabhupāda:''' So how they can be God conscious without being purified? | ||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' No, we are very glad to meet together, and we are ready to help you in your research work, provided you take our help. That will be very nice for you. | '''Prabhupāda:''' No, we are very glad to meet together, and we are ready to help you in your research work, provided you take our help. That will be very nice for you. | ||

Revatīnandana: I'll say one thing. If you want to see where in the world people are experiencing God, experiencing their relationship with God, you should examine this Hare Kṛṣṇa movement, I think. | '''Revatīnandana:''' I'll say one thing. If you want to see where in the world people are experiencing God, experiencing their relationship with God, you should examine this Hare Kṛṣṇa movement, I think. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, well I've, I've . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, well I've, I've . . . | ||

Revatīnandana: You'll see people who are living in every minute of every day in relation with God, and their experience is joyful . . . | '''Revatīnandana:''' You'll see people who are living in every minute of every day in relation with God, and their experience is joyful . . . | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: . . . and full of knowledge. | '''Revatīnandana:''' . . . and full of knowledge. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | ||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: No, no. I agree. | Sir Alistair Hardy: No, no. I agree. | ||

Revatīnandana: "Eastern-Western" will not help. | '''Revatīnandana:''' "Eastern-Western" will not help. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: No, I get example to both, both from the East and from the West. | Sir Alistair Hardy: No, I get example to both, both from the East and from the West. | ||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

With all these blunt senses, how can we . . . we cannot understand even the Personality of Godhead, what to speak of other things. "God is a person"—it is a very difficult subject matter for ordinary man to take it. Very difficult subject. That is stated in the . . . even the demigods, they cannot understand. That is . . . because he's thinking materially that, "This cosmic manifestation, then creation, is so big, and it is created by a person. How it is possible?" But . . . because they do not know what is that person. Simply by the word "person," he is afraid: "Oh, oh, oh, oh." | With all these blunt senses, how can we . . . we cannot understand even the Personality of Godhead, what to speak of other things. "God is a person"—it is a very difficult subject matter for ordinary man to take it. Very difficult subject. That is stated in the . . . even the demigods, they cannot understand. That is . . . because he's thinking materially that, "This cosmic manifestation, then creation, is so big, and it is created by a person. How it is possible?" But . . . because they do not know what is that person. Simply by the word "person," he is afraid: "Oh, oh, oh, oh." | ||

Revatīnandana: "He's like me. I can't do it; therefore not a person." | '''Revatīnandana:''' "He's like me. I can't do it; therefore not a person." | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: "No person except He's like me." | '''Revatīnandana:''' "No person except He's like me." | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. Therefore the Vedic scripture says, ''īśvaraḥ paramaḥ kṛṣṇaḥ sac-cid-ānanda-vigrahaḥ'' (Bs. 5.1). His person is different, ''sac-cid-ānanda''. That is not exactly with our personality. This is material. This is temporary personality. Now I am man. Next time I may become dog, next time become demigod. It is changing. It is not eternal, ''sat''. So God is not like that. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. Therefore the Vedic scripture says, ''īśvaraḥ paramaḥ kṛṣṇaḥ sac-cid-ānanda-vigrahaḥ'' (Bs. 5.1). His person is different, ''sac-cid-ānanda''. That is not exactly with our personality. This is material. This is temporary personality. Now I am man. Next time I may become dog, next time become demigod. It is changing. It is not eternal, ''sat''. So God is not like that. | ||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Hmm. Yes. So you have got this ''Bhagavad-gītā'' now, ''As It is''. Kindly take it. That will help you in your research work. And whenever you kindly ask us in some question, we are prepared to help you. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Hmm. Yes. So you have got this ''Bhagavad-gītā'' now, ''As It is''. Kindly take it. That will help you in your research work. And whenever you kindly ask us in some question, we are prepared to help you. | ||

Revatīnandana: One thing I noticed, at one point you mentioned that you only have a few years to go, and you're working on this particular subject of how religion is experienced today. Do you really think you only have a few years to go? | '''Revatīnandana:''' One thing I noticed, at one point you mentioned that you only have a few years to go, and you're working on this particular subject of how religion is experienced today. Do you really think you only have a few years to go? | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, I don't know, but I . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, I don't know, but I . . . | ||

| Line 187: | Line 187: | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm getting on. | Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm getting on. | ||

Revatīnandana: That's right. | '''Revatīnandana:''' That's right. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm seventy-seven. | Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm seventy-seven. | ||

Revatīnandana: Well, are you really seventy-seven? | '''Revatīnandana:''' Well, are you really seventy-seven? | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm seventy-seven, yes. | Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm seventy-seven, yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: But are you really seventy-seven? You see what I mean? | '''Revatīnandana:''' But are you really seventy-seven? You see what I mean? | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: Well . . . | ||

Revatīnandana: When does the work begin of actually knowing God, to actually know God? When does that business begin? Actually, we think that when this body is finished, we are not finished. But if we're not working toward God, we'll come back here and work again, because we're working in some other direction. | '''Revatīnandana:''' When does the work begin of actually knowing God, to actually know God? When does that business begin? Actually, we think that when this body is finished, we are not finished. But if we're not working toward God, we'll come back here and work again, because we're working in some other direction. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: So to be working in the vicinity of God, as you are, that's good, but to try to know God, that's the ultimate destination. | '''Revatīnandana:''' So to be working in the vicinity of God, as you are, that's good, but to try to know God, that's the ultimate destination. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, well, that's . . . yes. Well, I agree. But I must think about getting back to . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, well, that's . . . yes. Well, I agree. But I must think about getting back to . . . | ||

Revatīnandana: They're bringing some fruit for you. | '''Revatīnandana:''' They're bringing some fruit for you. | ||

'''Mukunda:''' In a few minutes they're bringing some refreshments. | '''Mukunda:''' In a few minutes they're bringing some refreshments. | ||

| Line 221: | Line 221: | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: 7:15. I mustn't be late . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: 7:15. I mustn't be late . . . | ||

Revatīnandana: 7:15 there'll be plenty of time. If we leave twenty minutes from now, by that time you will have had a little . . . | '''Revatīnandana:''' 7:15 there'll be plenty of time. If we leave twenty minutes from now, by that time you will have had a little . . . | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, I . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, I . . . | ||

Revatīnandana: They're bringing something right now. | '''Revatīnandana:''' They're bringing something right now. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Very kind. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Very kind. | ||

| Line 237: | Line 237: | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: A temple in southern India. | Sir Alistair Hardy: A temple in southern India. | ||

Revatīnandana: Which one? | '''Revatīnandana:''' Which one? | ||

'''Mukunda:''' Rāmeśvaram. | '''Mukunda:''' Rāmeśvaram. | ||

| Line 247: | Line 247: | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Rāmeś . . . I'm sorry. I pronounced it wrong. Rāmeśvaram. There, pilgrims bring water from the Ganges. They have a pool in which they keep it, I think. I'm not quite sure if I understood, but I think that over the period, all pilgrims bring water from the Ganges. And I think this water in this pool is Ganges water, which is continually added to by pilgrims coming. I'm not sure about that. That's what I understood, but I don't know. I'd a rather amusing experience there. I was doing a drawing . . . I was very fascinated. It's very beautiful pagoda-like entrances, north, east, south . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: Rāmeś . . . I'm sorry. I pronounced it wrong. Rāmeśvaram. There, pilgrims bring water from the Ganges. They have a pool in which they keep it, I think. I'm not quite sure if I understood, but I think that over the period, all pilgrims bring water from the Ganges. And I think this water in this pool is Ganges water, which is continually added to by pilgrims coming. I'm not sure about that. That's what I understood, but I don't know. I'd a rather amusing experience there. I was doing a drawing . . . I was very fascinated. It's very beautiful pagoda-like entrances, north, east, south . . . | ||

Revatīnandana: Temple gates. He is fascinated with them. | '''Revatīnandana:''' Temple gates. He is fascinated with them. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Temple gates. Yes. And I was making a drawing of this. So I had a very big crowd around me. And my Indian friends . . . I'd been staying at Mandapam, which is the . . . it was a naval settlement before, but it was really a center of the Indian fisheries. My biological interest had always been in the sea. And these friends came over, and they left this case while they went to take photographs. And they came back. And so the crowd were very excited. "Would you like to know what they're saying?" | Sir Alistair Hardy: Temple gates. Yes. And I was making a drawing of this. So I had a very big crowd around me. And my Indian friends . . . I'd been staying at Mandapam, which is the . . . it was a naval settlement before, but it was really a center of the Indian fisheries. My biological interest had always been in the sea. And these friends came over, and they left this case while they went to take photographs. And they came back. And so the crowd were very excited. "Would you like to know what they're saying?" | ||

| Line 257: | Line 257: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' No, you can keep it here. | '''Prabhupāda:''' No, you can keep it here. | ||

Revatīnandana: Perhaps if you keep your case there. | '''Revatīnandana:''' Perhaps if you keep your case there. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Oh. My case, yes. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Oh. My case, yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: You can use it like a little table. | '''Revatīnandana:''' You can use it like a little table. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: Thank you. Such a huge . . . oh, now can I have . . . I'd like some of this. Yes. Put that down. Put that down. | Sir Alistair Hardy: Thank you. Such a huge . . . oh, now can I have . . . I'd like some of this. Yes. Put that down. Put that down. | ||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: That's a great problem in biology, how did life arise from the inorganic matter. | Sir Alistair Hardy: That's a great problem in biology, how did life arise from the inorganic matter. | ||

Revatīnandana: Quite a problem. We don't agree. (laughs) We think that it didn't. | '''Revatīnandana:''' Quite a problem. We don't agree. (laughs) We think that it didn't. | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: No? I say, that's . . . | Sir Alistair Hardy: No? I say, that's . . . | ||

| Line 295: | Line 295: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Why not the "Divine person"? Wherefrom flame comes? | '''Prabhupāda:''' Why not the "Divine person"? Wherefrom flame comes? | ||

Revatīnandana: He says, now how to find out the Divine Person from whom the flame comes? Just like you were talking about how God is a manifestation of power, in your statement. But the manifestation of power, we always find it in relation with a source of power. Just like the sunlight is a manifestation of the power, and this great power of the sunlight, they're tapping it for electricity and so many things now. But that sunlight is not an independent entity. It's dependent on the source. | '''Revatīnandana:''' He says, now how to find out the Divine Person from whom the flame comes? Just like you were talking about how God is a manifestation of power, in your statement. But the manifestation of power, we always find it in relation with a source of power. Just like the sunlight is a manifestation of the power, and this great power of the sunlight, they're tapping it for electricity and so many things now. But that sunlight is not an independent entity. It's dependent on the source. | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' And Veda also points out, ''yato vā imāni bhūtāni jāyante'' (''Taittirīya Upaniṣad'' 3.1). | '''Prabhupāda:''' And Veda also points out, ''yato vā imāni bhūtāni jāyante'' (''Taittirīya Upaniṣad'' 3.1). | ||

| Line 313: | Line 313: | ||

(break) . . . ''ācari prabhu jīve śikhāilā.'' | (break) . . . ''ācari prabhu jīve śikhāilā.'' | ||

Revatīnandana: ''Caitanya-caritāmṛta''? | '''Revatīnandana:''' ''Caitanya-caritāmṛta''? | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: I recognize the Bengali. What's the . . .? | '''Revatīnandana:''' I recognize the Bengali. What's the . . .? | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' You should teach philosophy by behaving yourself. | '''Prabhupāda:''' You should teach philosophy by behaving yourself. | ||

Revatīnandana: Very nice. So simple. (break) | '''Revatīnandana:''' Very nice. So simple. (break) | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' . . . talked with many gentleman, lawyer. That Goldsmith, he was against war, but when I asked him, "Whether you are meat-eaters, killing animals?" "Yes, that is our food." So if the poor animals can become your food, the big nation can say: "The small nation is my food. I can kill them. We can kill them." Everyone can say. And that is happening, like "Might is right." | '''Prabhupāda:''' . . . talked with many gentleman, lawyer. That Goldsmith, he was against war, but when I asked him, "Whether you are meat-eaters, killing animals?" "Yes, that is our food." So if the poor animals can become your food, the big nation can say: "The small nation is my food. I can kill them. We can kill them." Everyone can say. And that is happening, like "Might is right." | ||

Revatīnandana: Yes. | '''Revatīnandana:''' Yes. | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. | ||

Revatīnandana: Goldsmith? He's a lawyer or something in Los Angeles? | '''Revatīnandana:''' Goldsmith? He's a lawyer or something in Los Angeles? | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Hmm. Hmm. Hmm. No, not Los Angeles. New York. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Hmm. Hmm. Hmm. No, not Los Angeles. New York. | ||

Revatīnandana: Oh, this Gould, Martin . . . some, his name was, in Los Angeles, Gould, Martin Gould. (break) | '''Revatīnandana:''' Oh, this Gould, Martin . . . some, his name was, in Los Angeles, Gould, Martin Gould. (break) | ||

Sir Alistair Hardy: . . . Rabindranath Tagore thought of in India today. I've always admired Rabindranath Tagore's very much, his poetic writings. Do people in India think much of him today? | Sir Alistair Hardy: . . . Rabindranath Tagore thought of in India today. I've always admired Rabindranath Tagore's very much, his poetic writings. Do people in India think much of him today? | ||

| Line 351: | Line 351: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' But his literatures are not read by our . . . a section. | '''Prabhupāda:''' But his literatures are not read by our . . . a section. | ||

Revatīnandana: Mostly in Bengal. And because he was accepted in the West, therefore they are very proud of it. But otherwise . . . (laughs) | '''Revatīnandana:''' Mostly in Bengal. And because he was accepted in the West, therefore they are very proud of it. But otherwise . . . (laughs) | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' The Russians read. I have heard that in your Oxford University there is study of Rabindranath's books? They study? | '''Prabhupāda:''' The Russians read. I have heard that in your Oxford University there is study of Rabindranath's books? They study? | ||

Revision as of 01:28, 8 September 2023

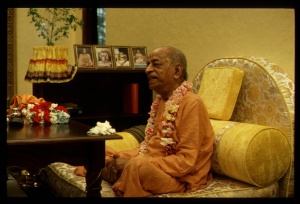

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

(Conversation with Sir Alistair Hardy)

Pradyumna: ". . . by the conditioned soul. Thus God is all-good, and God is all-merciful. Antaḥ praviṣṭaḥ śāstā janānām. The living entity forgets as soon as he quits his present body, but he begins his work again, initiated by the Supreme Lord. Although he forgets, the Lord gives him the intelligence to renew his work where he ended his last life. So not only does the living entity enjoy or suffer in this world according to the dictation from the Supreme Lord situated locally in the heart, but he receives the opportunity to understand Vedas from Him. If one is serious to understand the Vedic knowledge, then Kṛṣṇa gives the required intelligence.

"Why does He present the Vedic knowledge for understanding? Because the living entity individually needs to understand Kṛṣṇa. Vedic literature confirms this. Yo 'sau sarvair vedair gīyate. In all Vedic literature, beginning from the four Vedas, Vedānta-sūtra and the Upaniṣads and Purāṇas, the glories of the Supreme Lord are celebrated. By performing Vedic rituals, discussing the Vedic philosophy and worshiping the Lord in devotional service, He is attained. Therefore the purpose of the Vedas is to understand Kṛṣṇa."

"The Vedas give us direction to understand Kṛṣṇa and the process of understanding. The ultimate goal is the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Vedānta-sūtra confirms this in the following words: tat tu samanvayāt (Vedānta-sūtra 1.1.4). One can attain perfection by understanding Vedic literature, and one can understand his relationship with the Supreme Personality of Godhead by performing the different processes. Thus one can approach Him, and at the end attain the supreme goal, who is no other than the Supreme Personality of Godhead. In this verse, however, the purpose of the Vedas, the understanding of the Vedas and the goal of Vedas are clearly defined."

Prabhupāda: So God is acting within the heart of everyone. Sarvasya cāhaṁ hṛdi sanniviṣṭaḥ (BG 15.15).

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes. That's what I certainly believe.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Sir Alistair Hardy: I certainly believe that. Oh, I think we're very close, really, in our views of God, except that I'm concentrating on studying the working of God in the people of today. You are studying the message of God given by Kṛṣṇa in the . . . and I'm trying to show they are the same, the same view as that revealed by Jesus and by other great . . .

Prabhupāda: No . . . when we speak of Veda, Veda means knowledge. So knowledge means knowledge of God. Any scripture that gives knowledge of God, that is Veda. Don't think that Vedas means that only the Sāma, Yajur, Atharva. Those who are following the principles to give knowledge about God, that is Veda. Veda means knowledge. Vetti veda vido jñāne. Vid-dhātu is called veda, vetti. Jñāne, when there is question of knowledge, these three forms are used: vetti, veda, vido, jñāne. Vinte vid vicaraṇe vidyate vid saptāyāṁ labhe vindati vindate. This is the vid-dhātu description. So vid-dhātu means to know.

So ultimate knowledge is to know God. That is real knowledge. Vedaiś ca sarvaiḥ (BG 15.15). Sarvaiḥ, all kinds of Vedas. All kinds, sarvaiḥ. So Bible can be taken as Vedas because it is trying to give knowledge about God. Maybe for a certain class of men; that is another thing. But the subject matter is how to know God. So that can be taken as also as Vedas. Because ultimate knowledge is how to know God. Bahūnāṁ janmanām ante jñānavān māṁ prapadyate (BG 7.19). So we accept Bible also as Vedas, but we simply say that they misinterpret the Biblic commandments. The Bible says, "Thou shall not kill," and the Christian people are killing, maintaining slaughterhouse. What is this? This is my question. How they'll understand God if they are so much implicated in sinful activities?

According to Vedas, there are four kinds of sinful activities: illicit sex, unnecessary killing of animals, intoxication and gambling. Yatra pāpaś catur-vidhaḥ. So God is purest. Paraṁ brahma paraṁ dhāma pavitraṁ paramaṁ bhavān (BG 10.12). How one can approach God if he leads a sinful life? That is our propagation. You give up this sinful life. Then you'll be able to understand God. You follow Christianity or Muhammadanism or Buddhism, it doesn't matter. You give up this sinful life.

Revatīnandana: In the Bible it says: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God."

Prabhupāda: Yes, yes.

Revatīnandana: It's possible to see God, but only if there's purity of heart. And a sinful person has not got that purity of heart.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, I . . . some of the very simplest people have been nearer to God than those of great intellectual standing. That's true.

Revatīnandana: Not "simple", sinful. Not simple. We're saying "sinful."

Prabhupāda: Sinful.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Oh, sinful! I . . . I thought . . . I thought you said . . . sorry.

Revatīnandana: Yes, it's, it's, it's sin . . . I'm saying . . . even in the Bible it says: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God."

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes.

Revatīnandana: And how can a . . . how will a sinful person have that purity of heart?

Sir Alistair Hardy: No, well, a sinful person hasn't got purity of heart. No, quite.

Revatīnandana: Yes.

Prabhupāda: So do you . . .? Don't you think that killing of animal is sinful activity?

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, it's a very difficult problem, because surely the whole of creation has been part of God's work, and the whole of evolution, building up to man, has consisted in the killing of animals, one species killing another.

Prabhupāda: So why a human being should be like one species of animal?

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, er, man should gradually should grow out of that. I agree. Yes.

Prabhupāda: That means he's in lowest stage, animal stage. Who is killing, that means he's in the animal stage. So how he can see God? Can animal, cats and dogs, can see God? That's not possible. How the animals can see God?

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, we don't know at all what . . .

Prabhupāda: No . . .

Sir Alistair Hardy: We can't . . .

Prabhupāda: Your Bible is meant for not the cats and dogs. It is meant for the human being.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes.

Prabhupāda: Our Vedas are not meant for the cats and dogs. All śāstras and scriptures and Vedas, they are meant for human being. So if human being remains on cats and dogs, how he can understand? If he voluntarily remains like the cats and dog, then how he can understand the Vedas or Bible or Koran? He cannot. Nāhaṁ prakāśaḥ sarvasya yoga-māyā-samāvṛtaḥ (BG 7.25). We have to become pure before understanding what is God.

Therefore every civilized society has got a type of religion to become purified so that he can understand God. Without being purified, how it is possible? That is not possible. So at least these things should be accepted as they are in the Bible, "Thou shall not kill. Thou shall not covet." Illicit sex life, intoxication, and killing of animals, these are in the Bible. Why they are not accepted? This is not our impositions. This is already there.

Revatīnandana: And in every scripture . . .

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Revatīnandana: . . . for purification there are so many processes.

Prabhupāda: So how they can be God conscious without being purified?

(pause)

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, I think you're probably getting tired, and I think I probably . . .

Prabhupāda: You can give some prasādam. Take some prasādam.

Sir Alistair Hardy: You don't know what the time is? Good gracious, quarter to six. Yes. (laughs)

Prabhupāda: No, we are very glad to meet together, and we are ready to help you in your research work, provided you take our help. That will be very nice for you.

Revatīnandana: I'll say one thing. If you want to see where in the world people are experiencing God, experiencing their relationship with God, you should examine this Hare Kṛṣṇa movement, I think.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, well I've, I've . . .

Revatīnandana: You'll see people who are living in every minute of every day in relation with God, and their experience is joyful . . .

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes.

Revatīnandana: . . . and full of knowledge.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes.

Mukunda: Actually, it's not that we're studying the past, but we study a principle called dharma, which means that principle of life which never changes.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes.

Mukunda: That's our main concern.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, I'd very much like to have records of experience, accounts of present-day experience. Although as I say, at the moment I'm rather tending to concentrate on the Western. I'm hoping to get scholars who are really Sanskrit scholars, and those people who can really understand the language of Oriental . . . (indistinct)

Prabhupāda: No, first thing is: this, this is a different science. Science of God is not material science. Simply material, academic career will not help.

Sir Alistair Hardy: No, no. I agree.

Revatīnandana: "Eastern-Western" will not help.

Sir Alistair Hardy: No, I get example to both, both from the East and from the West.

Prabhupāda: Simply by becoming Sanskrit scholar or Latin scholar, it is not sufficient. He must be God-realized, purified. Then it is possible. Ataḥ śrī-kṛṣṇa-nāmādi na bhaved grāhyam indriyaiḥ (Brs. 1.2.234): "By your these blunt senses it is not possible to understand what is God, what is His form, what is His name, what is His quality, what is His kingdom, what is His paraphernalia." These things are to be understood.

God means . . . just like when we speak of "king." King does not mean alone. King means he has got his queen, he has got his kingdom, he has got his secretary, he has got his minister, he has got his palace, he has . . . so many things, king, royal. When we speak of Queen, we immediately remember the Buckingham Palace, his (her) bodyguard and so many, so many other things. Similarly, God means He has got His entourage also, everything. He's not alone. To understand God means to understand everything of God—His name, His fame, His līlā, His pastimes. So nāmādi.

With all these blunt senses, how can we . . . we cannot understand even the Personality of Godhead, what to speak of other things. "God is a person"—it is a very difficult subject matter for ordinary man to take it. Very difficult subject. That is stated in the . . . even the demigods, they cannot understand. That is . . . because he's thinking materially that, "This cosmic manifestation, then creation, is so big, and it is created by a person. How it is possible?" But . . . because they do not know what is that person. Simply by the word "person," he is afraid: "Oh, oh, oh, oh."

Revatīnandana: "He's like me. I can't do it; therefore not a person."

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Revatīnandana: "No person except He's like me."

Prabhupāda: Yes. Therefore the Vedic scripture says, īśvaraḥ paramaḥ kṛṣṇaḥ sac-cid-ānanda-vigrahaḥ (Bs. 5.1). His person is different, sac-cid-ānanda. That is not exactly with our personality. This is material. This is temporary personality. Now I am man. Next time I may become dog, next time become demigod. It is changing. It is not eternal, sat. So God is not like that.

Just like Kṛṣṇa says, sambhavāmy ātma-māyayā (BG 4.6). He does not come here being forced by the material energy. He comes by His spiritual energy. Sambhavāmy ātma-māyayā. Find out this. Yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir bhavati bhārata (BG 4.7). Therefore, as soon as He's accepted as ordinary man, avajānanti māṁ mūḍhā mānuṣīṁ tanum āśritam, paraṁ bhāvam ajānantaḥ (BG 9.11). He does not know what is the power behind that.

(aside) Read it.

Pradyumna: Ajo 'pi sann avyayātmā bhūtānām īśvaro 'pi san, prakṛtiṁ svām adhiṣṭhāya . . .

Prabhupāda: Prakṛtiṁ svām adhiṣṭhāya.

Pradyumna: Sambhavāmy ātma-māyayā (BG 4.6). "Although I am unborn, and My transcendental body never deteriorates, and although I am the Lord of all sentient beings, I still appear in every millennium in My original, transcendental form."

Prabhupāda: Read the purport.

Pradyumna: "The Lord has spoken about the peculiarity of His birth. Although He may appear like an ordinary person, He remembers everything of His many, many past births, whereas a common man cannot remember what he has done even a few hours before. If someone is asked what he did exactly at the same time one day earlier, it would be very difficult for a common man to answer immediately. He would surely have to dredge his memory to recall what he was doing exactly at the same time one day before. And yet, men often dare claim to be God, or Kṛṣṇa. One should not be misled by such meaningless claims."

"Then again, the Lord explains His prakṛti, or His form. Prakṛti means nature, as well as svarūpa, or one's own form. The Lord says that He appears in His own body. He does not change His body, as the common living entity changes from one body to another. The conditioned soul may have one kind of body in the present birth, but he has a different body in the next birth. In the material world the living entity has no fixed body, but transmigrates from one body to another. The Lord, however, does not do so. Whenever He appears, He does so in the same original body by His internal potency. In other words, Kṛṣṇa appears in this material world in His original, eternal form, with two hands, holding a flute. He appears exactly in His eternal body, uncontaminated by this material world."

"Although He appears in the same transcendental body and is the Lord of the universe, it still appears that He takes His birth like an ordinary living entity. Despite the fact Lord Kṛṣṇa grows from childhood to boyhood and from boyhood to youth, astonishingly enough, He never ages beyond youth. At the time of the Battle of Kurukṣetra, He had many grandchildren at home, or in other words, He had sufficiently aged by material calculations. Still, He looked just like a young man, twenty or twenty-five years old. We never see a picture of Kṛṣṇa in old age because He never grows old like us, although He is the oldest person in the entire . . ."

Prabhupāda: Advaitam acyutam anādim ananta-rūpam ādyaṁ purāṇa-puruṣaṁ nava-yauvanaṁ ca (Bs. 5.33). Purāṇa-puruṣa, the oldest man, oldest living entity, but nava-yauvana, just like young man. Nava-yauvanaṁ ca. Advaitam acyutam anādim ananta-rūpam ādyaṁ purāṇa-puruṣam. Purāṇa means oldest, because He's the origin of all living entities. But nava-yauvanaṁ ca, just a fresh young man. Hmm. Go on.

Pradyumna: ". . . and, although He is the oldest person in the whole creation, He is the oldest person in the whole creation—past, present and future. Neither His body nor His intelligence ever deteriorates or changes. Therefore it is clear that in spite of His being in the material world, He is the same unborn, eternal form of bliss and knowledge, changeless in His transcendental body and intelligence. Factually, His appearance and disappearance is like the sun's rising, moving before us, and then disappearing from our eyesight."

"When the sun is out of sight, we think that the sun is set, and when the sun is before our eyes, we think that the sun is on the horizon. Actually, the sun is always in its fixed position, but owing to our defective, insufficient senses, we calculate the appearance and disappearance of the sun in the sky. And because His appearance and disappearance are completely different from that of any ordinary, common living entity, it is evident that He is eternal, blissful knowledge by His internal potency—and He is never contaminated by material nature."

"The Vedas also confirm that the Supreme Personality of Godhead is unborn, yet He still appears to take His birth in multimanifestations. The Vedic supplementary literatures also confirm that even though the Lord appears to be taking His birth, He is still without change of body. In the Bhāgavatam, He appears before His mother as Nārāyaṇa, with four hands and the decorations of the six kinds of full opulences. His appearance in His original, eternal form is His causeless mercy, according to the Viśva-kośa dictionary. The Lord is conscious of all of His previous appearances and disappearances, but a common living entity forgets everything about his past body as soon as he gets another body."

"He is the Lord of all living entities because He performs wonderful and superhuman activities while He is on this earth. Therefore, the Lord is always the same Absolute Truth and is without differentiation between His form and self, or between His quality and body. A question may now be raised as to why the Lord appears and disappears in this world. This is explained in the next verse."

Prabhupāda: Hmm. Yes. So you have got this Bhagavad-gītā now, As It is. Kindly take it. That will help you in your research work. And whenever you kindly ask us in some question, we are prepared to help you.

Revatīnandana: One thing I noticed, at one point you mentioned that you only have a few years to go, and you're working on this particular subject of how religion is experienced today. Do you really think you only have a few years to go?

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well, I don't know, but I . . .

Prabhupāda: No, that is material calculation.

Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm getting on.

Revatīnandana: That's right.

Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm seventy-seven.

Revatīnandana: Well, are you really seventy-seven?

Sir Alistair Hardy: I'm seventy-seven, yes.

Revatīnandana: But are you really seventy-seven? You see what I mean?

Sir Alistair Hardy: Well . . .

Revatīnandana: When does the work begin of actually knowing God, to actually know God? When does that business begin? Actually, we think that when this body is finished, we are not finished. But if we're not working toward God, we'll come back here and work again, because we're working in some other direction.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes.

Revatīnandana: So to be working in the vicinity of God, as you are, that's good, but to try to know God, that's the ultimate destination.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, well, that's . . . yes. Well, I agree. But I must think about getting back to . . .

Revatīnandana: They're bringing some fruit for you.

Mukunda: In a few minutes they're bringing some refreshments.

Prabhupāda: Can you wait?

Mukunda: I can take you straight to the station.

Sir Alistair Hardy: And I must catch at least the 7:15 train.

Mukunda: Oh, yes, definitely.

Sir Alistair Hardy: 7:15. I mustn't be late . . .

Revatīnandana: 7:15 there'll be plenty of time. If we leave twenty minutes from now, by that time you will have had a little . . .

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, I . . .

Revatīnandana: They're bringing something right now.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Very kind.

Prabhupāda: You have to go to Oxford?

Sir Alistair Hardy: Yes, yes, I must. I've been to the great temple of Rāmeśvaram in southern India, south of Madras. It was a very fine experience.

Prabhupāda: All the temples you have seen? South India?

Sir Alistair Hardy: A temple in southern India.

Revatīnandana: Which one?

Mukunda: Rāmeśvaram.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Rāmeśvaram.

Prabhupāda: Rāmeśvaram.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Rāmeś . . . I'm sorry. I pronounced it wrong. Rāmeśvaram. There, pilgrims bring water from the Ganges. They have a pool in which they keep it, I think. I'm not quite sure if I understood, but I think that over the period, all pilgrims bring water from the Ganges. And I think this water in this pool is Ganges water, which is continually added to by pilgrims coming. I'm not sure about that. That's what I understood, but I don't know. I'd a rather amusing experience there. I was doing a drawing . . . I was very fascinated. It's very beautiful pagoda-like entrances, north, east, south . . .

Revatīnandana: Temple gates. He is fascinated with them.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Temple gates. Yes. And I was making a drawing of this. So I had a very big crowd around me. And my Indian friends . . . I'd been staying at Mandapam, which is the . . . it was a naval settlement before, but it was really a center of the Indian fisheries. My biological interest had always been in the sea. And these friends came over, and they left this case while they went to take photographs. And they came back. And so the crowd were very excited. "Would you like to know what they're saying?"

And so I said, "Yes." So he said: "What they're saying is, 'Isn't he wonderful! Isn't he wonderful! He's taking photographs with his fingers.' " They were more used to photographs, I think. They'd never seen anyone doing an actual . . . they'd seen symbolic drawings, but . . . I was reproducing the temple gates, and they said I was taking photographs with my fingers. I thought that was a wonderful expression really, "Taking photographs with my fingers." (someone brings in prasādam) Oh, thank you. I say, how lovely.

Pradyumna: (indistinct) . . . can use the table?

Prabhupāda: No, you can keep it here.

Revatīnandana: Perhaps if you keep your case there.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Oh. My case, yes.

Revatīnandana: You can use it like a little table.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Thank you. Such a huge . . . oh, now can I have . . . I'd like some of this. Yes. Put that down. Put that down.

Pradyumna: You know the Indian style of . . .

Sir Alistair Hardy: I must follow you, how you eat this. I don't know how you . . .

Prabhupāda: Anything you can eat, as you like. There is no restriction.

Pradyumna: That's called purī.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Purīs, yes, that's lovely. Yes.

Pradyumna: You probably had those in India.

(break)

Sir Alistair Hardy: . . . through India, going out to the Far East. I've been out advising on the setting up of a fishery, biological research, at Hong Kong. But I never believe in going straight out, and I've always stopped in India, various places, very little, short time. (eating) I had a great friend, Professor Bower, who was professor of zoology at Lucknow. He then became the vice-chancellor of Patna. But he overworked very badly, and he had a breakdown, and then . . . but he was an awfully nice man, and I stayed with him in Lucknow.

Prabhupāda: This zoology is another subject matter, whether life began from matter or matter began from life.

Sir Alistair Hardy: That's a great problem in biology, how did life arise from the inorganic matter.

Revatīnandana: Quite a problem. We don't agree. (laughs) We think that it didn't.

Sir Alistair Hardy: No? I say, that's . . .

Prabhupāda: Life also came from life; matter also came from matter, er, life. That is explained in the Vedānta-sūtra: janmādyasya yataḥ. And it is explained in Bhagavad-gītā also: ahaṁ sarvasya prabhavaḥ (BG 10.8). So there is no difficulty.

Sir Alistair Hardy: But life may have arisen from the inorganic by the breathing in of the Divine into it. And there's no doubt that our bodies are material, but within our bodies is this divine, what I call the "divine flame" in one of my . . . (indistinct)

Prabhupāda: Why not the "Divine person"? Wherefrom flame comes?

Revatīnandana: He says, now how to find out the Divine Person from whom the flame comes? Just like you were talking about how God is a manifestation of power, in your statement. But the manifestation of power, we always find it in relation with a source of power. Just like the sunlight is a manifestation of the power, and this great power of the sunlight, they're tapping it for electricity and so many things now. But that sunlight is not an independent entity. It's dependent on the source.

Prabhupāda: And Veda also points out, yato vā imāni bhūtāni jāyante (Taittirīya Upaniṣad 3.1).

(to Mukunda:) So your New York going is suspended now?

Mukunda: No, I'm still going.

Prabhupāda: When you are going?

Mukunda: As soon as possible.

(pause) (break)

Prabhupāda: . . . then talk of all this moral instruction. If you are killing yourself, then why do you object? Why?

(break) . . . ācari prabhu jīve śikhāilā.

Revatīnandana: Caitanya-caritāmṛta?

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Revatīnandana: I recognize the Bengali. What's the . . .?

Prabhupāda: You should teach philosophy by behaving yourself.

Revatīnandana: Very nice. So simple. (break)

Prabhupāda: . . . talked with many gentleman, lawyer. That Goldsmith, he was against war, but when I asked him, "Whether you are meat-eaters, killing animals?" "Yes, that is our food." So if the poor animals can become your food, the big nation can say: "The small nation is my food. I can kill them. We can kill them." Everyone can say. And that is happening, like "Might is right."

Revatīnandana: Yes.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Revatīnandana: Goldsmith? He's a lawyer or something in Los Angeles?

Prabhupāda: Hmm. Hmm. Hmm. No, not Los Angeles. New York.

Revatīnandana: Oh, this Gould, Martin . . . some, his name was, in Los Angeles, Gould, Martin Gould. (break)

Sir Alistair Hardy: . . . Rabindranath Tagore thought of in India today. I've always admired Rabindranath Tagore's very much, his poetic writings. Do people in India think much of him today?

Prabhupāda: What about that?

Haṁsadūta: Rabindranath Tagore. If his writings are highly considered by people in India.

Prabhupāda: No, not at all.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Not at all. No.

Prabhupāda: What is his writings? So many speculation. That's all. But it has got little similarity to Vaiṣṇavism. His Gītāñjali . . .

Sir Alistair Hardy: He had a great reputation in the Western world.

Prabhupāda: But his literatures are not read by our . . . a section.

Revatīnandana: Mostly in Bengal. And because he was accepted in the West, therefore they are very proud of it. But otherwise . . . (laughs)

Prabhupāda: The Russians read. I have heard that in your Oxford University there is study of Rabindranath's books? They study?

Sir Alistair Hardy: They study which books?

Prabhupāda: Rabindranath's.

Sir Alistair Hardy: Oh, I think they produce some of them, yes. He gave a course of lectures in Oxford about 1923, I think, or '22 or '23, which were very well attended. I wasn't there, unfortunately, but I read them.

Prabhupāda: 1953?

Haṁsadūta: '23.

Sir Alistair Hardy: '23.

Prabhupāda: '23.

Sir Alistair Hardy: '23. (end)

- 1973 - Conversations

- 1973 - Lectures and Conversations

- 1973 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- 1973-07 - Lectures, Conversations and Letters

- Conversations - Europe

- Conversations - Europe, England - London

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Europe

- Lectures, Conversations and Letters - Europe, England - London

- Conversations with Academics

- Audio Files 30.01 to 45.00 Minutes