710905 - Conversation - London: Difference between revisions

RasaRasika (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Śyāmasundara:" to "'''Śyāmasundara:'''") |

RasaRasika (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Mensa Member:" to "'''Mensa Member:'''") |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

So in this way those who are advanced in knowledge, ''budhā'', they engage themself in the service of the original cause of all causes. He's the cause of all causes, but He has no cause. That is God. ''Anādir ādir govindam''. He has no cause, but He's the cause of all life. That is God. Just like I am the effect; my father is the cause. Similarly, my grandfather is the cause of my father. My grandfather is the effect of the cause great-grandfather. You go on searching out, searching out. So when you find out the original cause, that is God. That is the definition of God. | So in this way those who are advanced in knowledge, ''budhā'', they engage themself in the service of the original cause of all causes. He's the cause of all causes, but He has no cause. That is God. ''Anādir ādir govindam''. He has no cause, but He's the cause of all life. That is God. Just like I am the effect; my father is the cause. Similarly, my grandfather is the cause of my father. My grandfather is the effect of the cause great-grandfather. You go on searching out, searching out. So when you find out the original cause, that is God. That is the definition of God. | ||

Mensa Member: Do you . . . (indistinct) . . . prime mover argument is who is the prime mover? What is the logical necessity for a first cause? Would you agree with that? | '''Mensa Member:''' Do you . . . (indistinct) . . . prime mover argument is who is the prime mover? What is the logical necessity for a first cause? Would you agree with that? | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, I think it's inherent in your definition of something that's omnipotent that it's very like saying it's necessary to have no beginning in order to have no end. It's really a concept. Whether it exists or not it doesn't matter. | Dr. Ware: Well, I think it's inherent in your definition of something that's omnipotent that it's very like saying it's necessary to have no beginning in order to have no end. It's really a concept. Whether it exists or not it doesn't matter. | ||

Mensa Member: Yes. Then even negatives imply limitation. If something has only positive attributes, it's limited if you exclude negative attributes. Or is that just a . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' Yes. Then even negatives imply limitation. If something has only positive attributes, it's limited if you exclude negative attributes. Or is that just a . . . | ||

Dr. Ware: Well no, if something has all attributes, we only cause, or call them to be caused, positive or negative because we have a tendency to want to think in terms of dichotomies, "good" and "bad," whereas really, if you're a scientist, you say: "This exists." It's only when morals come in, you say some things are good and some things are bad, and you start making antinomies. Really, your Godhead would contain all those things, and to Him there's no such thing as good or evil, but to Him they are all of value. It's man who saw the good and evil. | Dr. Ware: Well no, if something has all attributes, we only cause, or call them to be caused, positive or negative because we have a tendency to want to think in terms of dichotomies, "good" and "bad," whereas really, if you're a scientist, you say: "This exists." It's only when morals come in, you say some things are good and some things are bad, and you start making antinomies. Really, your Godhead would contain all those things, and to Him there's no such thing as good or evil, but to Him they are all of value. It's man who saw the good and evil. | ||

Mensa Member: I wasn't particularly thinking of the good and evil value. I was simply thinking of negative attributes. | '''Mensa Member:''' I wasn't particularly thinking of the good and evil value. I was simply thinking of negative attributes. | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, I'm sorry, I don't know quite what you mean. Unless you define the negative attribute, I'm not quite sure what it is. | Dr. Ware: Well, I'm sorry, I don't know quite what you mean. Unless you define the negative attribute, I'm not quite sure what it is. | ||

Mensa Member: Not beginning. | '''Mensa Member:''' Not beginning. | ||

Dr. Ware: Well that, with respect, I think, doesn't really follow, because there're some things that don't have opposites or negatives, although (in) nature. This is what I say, that there are certain categories of things to which if somebody says: "Now what's the opposite of that?" you'd have to say: "There isn't an opposite," because it isn't the sort of thing to have an opposite. | Dr. Ware: Well that, with respect, I think, doesn't really follow, because there're some things that don't have opposites or negatives, although (in) nature. This is what I say, that there are certain categories of things to which if somebody says: "Now what's the opposite of that?" you'd have to say: "There isn't an opposite," because it isn't the sort of thing to have an opposite. | ||

Mensa Member: So you wouldn't accept the prime mover either? | '''Mensa Member:''' So you wouldn't accept the prime mover either? | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, it's not an argument; it's a postulate. I don't accept it. I mean, you have to accept it if you're going to . . . you know the total . . . (indistinct) . . . so to speak. You can't have it half way. | Dr. Ware: Well, it's not an argument; it's a postulate. I don't accept it. I mean, you have to accept it if you're going to . . . you know the total . . . (indistinct) . . . so to speak. You can't have it half way. | ||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

Dr. Ware: Yes, light and dark are subjective reactions. Really, the scientists would say there are wave lengths of a certain type in one part of the universe and in the other they're absent. But until you have an observer, you can't notice that. | Dr. Ware: Yes, light and dark are subjective reactions. Really, the scientists would say there are wave lengths of a certain type in one part of the universe and in the other they're absent. But until you have an observer, you can't notice that. | ||

Mensa Member: But the planet would still be there . . . (indistinct) | '''Mensa Member:''' But the planet would still be there . . . (indistinct) | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, Samuel Johnson quite rightly refuted that by taking . . . (indistinct) | Dr. Ware: Well, Samuel Johnson quite rightly refuted that by taking . . . (indistinct) | ||

| Line 185: | Line 185: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Actually, there is no darkness. Take it sun as, it is whole. There is no darkness and everything is in sunshine. All the planets, they are rotating in sunshine. So under certain condition, one part is becoming dark, another part is light. But actually the whole universe is full with sunshine. ''Sarvaṁ khalv idaṁ brahma'' (''Chāndogya Upaniṣad'' 3.14.1). That is the exact definition given in Sanskrit: everything is light, ''brahma''. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Actually, there is no darkness. Take it sun as, it is whole. There is no darkness and everything is in sunshine. All the planets, they are rotating in sunshine. So under certain condition, one part is becoming dark, another part is light. But actually the whole universe is full with sunshine. ''Sarvaṁ khalv idaṁ brahma'' (''Chāndogya Upaniṣad'' 3.14.1). That is the exact definition given in Sanskrit: everything is light, ''brahma''. | ||

Mensa Member: That's another postulate. | '''Mensa Member:''' That's another postulate. | ||

Dr. Ware: You can build any theory according to the number of postulates you're willing to accept which cannot be analyzed, including the basis of science, that the atom, as originally thought of by Theocritus and others, is this thing that you cannot go beyond and cap down . . . (indistinct) . . . and saying with your philosophy or your theology that you go down until you can find nothing, except that you say that ''causa causam'', and then you build back again from that. But that's what I was saying earlier on: the . . . (indistinct) . . . is very close to the Unitarian position in Christianity. | Dr. Ware: You can build any theory according to the number of postulates you're willing to accept which cannot be analyzed, including the basis of science, that the atom, as originally thought of by Theocritus and others, is this thing that you cannot go beyond and cap down . . . (indistinct) . . . and saying with your philosophy or your theology that you go down until you can find nothing, except that you say that ''causa causam'', and then you build back again from that. But that's what I was saying earlier on: the . . . (indistinct) . . . is very close to the Unitarian position in Christianity. | ||

| Line 205: | Line 205: | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, his position would be the same as yours, wouldn't it? In religion? | Dr. Ware: Well, his position would be the same as yours, wouldn't it? In religion? | ||

Mensa Member: You mean the Tibetan Buddhist attitude towards the Godhead is the same as the Kṛṣṇas? | '''Mensa Member:''' You mean the Tibetan Buddhist attitude towards the Godhead is the same as the Kṛṣṇas? | ||

Dr. Ware: Yes. They have that same basis. | Dr. Ware: Yes. They have that same basis. | ||

| Line 213: | Line 213: | ||

Dr. Ware: No. They believe in this existence of a "Goddess" if you like. | Dr. Ware: No. They believe in this existence of a "Goddess" if you like. | ||

Mensa Member: It's very subjective. The Buddhist point of view in general seems to be very much that of the nineteenth century English rationalist, the agnostic, in its visual sense. | '''Mensa Member:''' It's very subjective. The Buddhist point of view in general seems to be very much that of the nineteenth century English rationalist, the agnostic, in its visual sense. | ||

Dr. Ware: That's why I say the Unitarian comes closest to it. | Dr. Ware: That's why I say the Unitarian comes closest to it. | ||

| Line 219: | Line 219: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' What is that? | '''Śyāmasundara:''' What is that? | ||

Mensa Member: Well, the fact that a Godhead is . . . is impossible to comprehend. It maybe or may not be in very brief terms. | '''Mensa Member:''' Well, the fact that a Godhead is . . . is impossible to comprehend. It maybe or may not be in very brief terms. | ||

Dr. Ware: But if you accept its existence, then it's present in everybody. Which is exactly what you're saying. Whether they utilize it, whether, as you call it, uncovered, or to the degree of which they are conscious of it, is a different thing. | Dr. Ware: But if you accept its existence, then it's present in everybody. Which is exactly what you're saying. Whether they utilize it, whether, as you call it, uncovered, or to the degree of which they are conscious of it, is a different thing. | ||

| Line 331: | Line 331: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. Just like here is the medicine, diabetic. So I have accepted this medicine through a bona fide doctor. Although it is meant for diabetes, I have not accepted this medicine, neither it is advised that this medicine should be accepted by a bona fide physician, so I cannot see properly whether it is good for me. But when the physician, qualified physician, says: "Yes, it is bona fide. You can use it in this way," that is nice. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. Just like here is the medicine, diabetic. So I have accepted this medicine through a bona fide doctor. Although it is meant for diabetes, I have not accepted this medicine, neither it is advised that this medicine should be accepted by a bona fide physician, so I cannot see properly whether it is good for me. But when the physician, qualified physician, says: "Yes, it is bona fide. You can use it in this way," that is nice. | ||

Mensa Member: Coming back to your previous point, if he made a mistake and it's the wrong medicine, would you say he cheated you? Is that the point you were getting at? | '''Mensa Member:''' Coming back to your previous point, if he made a mistake and it's the wrong medicine, would you say he cheated you? Is that the point you were getting at? | ||

Dr. Ware: This is what worried me. | Dr. Ware: This is what worried me. | ||

| Line 337: | Line 337: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' Yes, because if he purports to be a physician . . . | '''Śyāmasundara:''' Yes, because if he purports to be a physician . . . | ||

Mensa Member: No, he is a physician, and he makes a mistake, a healthy, genuine mistake. | '''Mensa Member:''' No, he is a physician, and he makes a mistake, a healthy, genuine mistake. | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Therefore we say we have to receive knowledge from a person who does not commit any mistake. That is our proposition. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Therefore we say we have to receive knowledge from a person who does not commit any mistake. That is our proposition. | ||

| Line 343: | Line 343: | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, that would be going like God. If you define it that way, you're . . . (indistinct) . . . aren't you? | Dr. Ware: Well, that would be going like God. If you define it that way, you're . . . (indistinct) . . . aren't you? | ||

Mensa Member: That does seem a bit . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' That does seem a bit . . . | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Therefore I said . . . | '''Prabhupāda:''' Therefore I said . . . | ||

| Line 359: | Line 359: | ||

Dr. Ware: Which may not, unfortunately . . . this is the danger of analogy. This medicine may work in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, and in the hundredth one it could kill the poor chap. Now you can't say that the physician was cheating in prescribing it for the hundredth chap, because he just didn't know. | Dr. Ware: Which may not, unfortunately . . . this is the danger of analogy. This medicine may work in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, and in the hundredth one it could kill the poor chap. Now you can't say that the physician was cheating in prescribing it for the hundredth chap, because he just didn't know. | ||

Mensa Member: (indistinct) . . . on the other hand, the other medicine might have worked. | '''Mensa Member:''' (indistinct) . . . on the other hand, the other medicine might have worked. | ||

Dr. Ware: Hmm. | Dr. Ware: Hmm. | ||

Mensa Member: It is very dangerous. Analogy's awfully dangerous. | '''Mensa Member:''' It is very dangerous. Analogy's awfully dangerous. | ||

Dr. Ware: But then some people have to have a concrete example, or they haven't any . . . (indistinct) . . . it's when you analyze the analogy that you can see it's difficult . . . | Dr. Ware: But then some people have to have a concrete example, or they haven't any . . . (indistinct) . . . it's when you analyze the analogy that you can see it's difficult . . . | ||

| Line 393: | Line 393: | ||

Dr. Ware: That's so. But it's only when they break out from that control by, let's say, making an observation or having an intuition that isn't inherent in the system of control in which they've been brought up that they make an advance of any sort. You see, people with . . . I always give this example of Sir Alexander Fleming and Florey and others. People have been trained that dirty petri dishes should be thrown away, because they're moldy, they will interfere with the experiment. This happens time again. Whereas a man suddenly thinks, "I will have a look at this. I'll ignore that." He breaks away from this control. | Dr. Ware: That's so. But it's only when they break out from that control by, let's say, making an observation or having an intuition that isn't inherent in the system of control in which they've been brought up that they make an advance of any sort. You see, people with . . . I always give this example of Sir Alexander Fleming and Florey and others. People have been trained that dirty petri dishes should be thrown away, because they're moldy, they will interfere with the experiment. This happens time again. Whereas a man suddenly thinks, "I will have a look at this. I'll ignore that." He breaks away from this control. | ||

Mensa Member: It wasn't anything new, simply a rearrangement of current, existing data. | '''Mensa Member:''' It wasn't anything new, simply a rearrangement of current, existing data. | ||

Dr. Ware: Nobody'd ever . . . they were controlled to reject it. This is what so often happens. Perry Mason is a wonderful example of that—a person who always picks out something that's been rejected in his . . . his celebrated works. | Dr. Ware: Nobody'd ever . . . they were controlled to reject it. This is what so often happens. Perry Mason is a wonderful example of that—a person who always picks out something that's been rejected in his . . . his celebrated works. | ||

Mensa Member: I don't know if Perry Mason is . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' I don't know if Perry Mason is . . . | ||

Dr. Ware: Oh, Perry Mason is a very popular courtroom . . . as they say, or trial lawyer, as they call it in America. A person called Erle Stanley Gardner has written a large number of books . . . | Dr. Ware: Oh, Perry Mason is a very popular courtroom . . . as they say, or trial lawyer, as they call it in America. A person called Erle Stanley Gardner has written a large number of books . . . | ||

| Line 417: | Line 417: | ||

Dr. Ware: The difficulty is, in any form of discussion like this, it's very fascinating, but it does show the limitations of transmission of feelings and ideas and all those complicated things by a simple verbal process, this is the real problem. | Dr. Ware: The difficulty is, in any form of discussion like this, it's very fascinating, but it does show the limitations of transmission of feelings and ideas and all those complicated things by a simple verbal process, this is the real problem. | ||

Mensa Member: I agree entirely. Zen immediately comes to mind, where the problem's recognized, immediately acted on, and it's admitted that there's an impossibility of transmission by an individual. | '''Mensa Member:''' I agree entirely. Zen immediately comes to mind, where the problem's recognized, immediately acted on, and it's admitted that there's an impossibility of transmission by an individual. | ||

Dr. Ware: This is where you can't get a feeling across by writing a textbook of it. I think . . . | Dr. Ware: This is where you can't get a feeling across by writing a textbook of it. I think . . . | ||

| Line 439: | Line 439: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' That is, that is of course later on; in the beginning you are a student of a lawyer. | '''Prabhupāda:''' That is, that is of course later on; in the beginning you are a student of a lawyer. | ||

Mensa Member: That's used for analogy, because some people have gone on . . . (indistinct) . . . no matter who they are. | '''Mensa Member:''' That's used for analogy, because some people have gone on . . . (indistinct) . . . no matter who they are. | ||

Dr. Ware: Yah. Yah. Well this is the only thing, "Seek and ye shall find, or be still and ye shall know." I think this is the essential feature that you've been saying is that, really, this grace comes to anybody if they're only willing to expect it. It's inherently there. | Dr. Ware: Yah. Yah. Well this is the only thing, "Seek and ye shall find, or be still and ye shall know." I think this is the essential feature that you've been saying is that, really, this grace comes to anybody if they're only willing to expect it. It's inherently there. | ||

Mensa Member: With respect . . . (indistinct) . . . among many other people, prove that it's absolutely impossible to establish a rational, umm, a rational grounding for religion. In other words, trying to logically prove axioms is logically impossible. | '''Mensa Member:''' With respect . . . (indistinct) . . . among many other people, prove that it's absolutely impossible to establish a rational, umm, a rational grounding for religion. In other words, trying to logically prove axioms is logically impossible. | ||

Dr. Ware: Yes . . . (indistinct) . . . not necessary. | Dr. Ware: Yes . . . (indistinct) . . . not necessary. | ||

| Line 457: | Line 457: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' She's to that point without having any rational knowledge. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' She's to that point without having any rational knowledge. | ||

Mensa Member: There's some . . . (indistinct) . . . simple people also . . . (indistinct) . . . people like Blake, for example, or Buddha . . . (indistinct) . . . simple person. It's not this sort of faith, only childlike faith—it's often found in simple people. | '''Mensa Member:''' There's some . . . (indistinct) . . . simple people also . . . (indistinct) . . . people like Blake, for example, or Buddha . . . (indistinct) . . . simple person. It's not this sort of faith, only childlike faith—it's often found in simple people. | ||

Dr. Ware: It certainly is easier for them, though. It's easier for the simple person, because he doesn't have all these mental, complicated doubts and, you know, arguments with himself. | Dr. Ware: It certainly is easier for them, though. It's easier for the simple person, because he doesn't have all these mental, complicated doubts and, you know, arguments with himself. | ||

Mensa Member: Yes. | '''Mensa Member:''' Yes. | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' It's said that as one progresses more and more in spiritual life he becomes simpler and more innocent. But in the beginning he may have had to comprehend it on some verbal level in order to . . . (indistinct) | '''Śyāmasundara:''' It's said that as one progresses more and more in spiritual life he becomes simpler and more innocent. But in the beginning he may have had to comprehend it on some verbal level in order to . . . (indistinct) | ||

| Line 493: | Line 493: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' No. No. Why? | '''Prabhupāda:''' No. No. Why? | ||

Mensa Member: That's true. | '''Mensa Member:''' That's true. | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' He said that sometimes someone may fear authority. That prevents them. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' He said that sometimes someone may fear authority. That prevents them. | ||

| Line 505: | Line 505: | ||

Dr. Ware: May I make one strange statement that I think it is rather true of the present world? People are always afraid of fear and love. It's almost as though it's something rather sissy or, you know, to get so mixed up with sentimentality. | Dr. Ware: May I make one strange statement that I think it is rather true of the present world? People are always afraid of fear and love. It's almost as though it's something rather sissy or, you know, to get so mixed up with sentimentality. | ||

Mensa Member: I don't know what it is rather than fear. | '''Mensa Member:''' I don't know what it is rather than fear. | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, I mean . . . if you don't know . . . if I were afraid of you because of absolute knowledge or . . . | Dr. Ware: Well, I mean . . . if you don't know . . . if I were afraid of you because of absolute knowledge or . . . | ||

Mensa Member: Yah. | '''Mensa Member:''' Yah. | ||

Dr. Ware: . . . terrified of the unknown. | Dr. Ware: . . . terrified of the unknown. | ||

Mensa Member: That's very true. That's why plan children and such like and things like the Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement who not only profess . . . (indistinct) . . . scare into lots of people. | '''Mensa Member:''' That's very true. That's why plan children and such like and things like the Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement who not only profess . . . (indistinct) . . . scare into lots of people. | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Just like the child is afraid of the father. There is affection. "My father is displeased if I do . . . Father has said, 'Don't touch this,' so I don't touch. My father has . . ." So that fear and affection, both is there. It is not simply that he is afraid of his father, but the affection is there. So to become obedient to the authority, there is a tinge of fear also, but that is based on affection. That is not actually . . . | '''Prabhupāda:''' Just like the child is afraid of the father. There is affection. "My father is displeased if I do . . . Father has said, 'Don't touch this,' so I don't touch. My father has . . ." So that fear and affection, both is there. It is not simply that he is afraid of his father, but the affection is there. So to become obedient to the authority, there is a tinge of fear also, but that is based on affection. That is not actually . . . | ||

| Line 543: | Line 543: | ||

Dr. Ware: I must say that's very interesting. | Dr. Ware: I must say that's very interesting. | ||

Mensa Member: Can I ask one last question? The ''Bhagavad-gītā''—do you accept that as historically . . . an historical fact? | '''Mensa Member:''' Can I ask one last question? The ''Bhagavad-gītā''—do you accept that as historically . . . an historical fact? | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Truth is historical fact is. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Truth is historical fact is. | ||

| Line 567: | Line 567: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' No. Battlefield, where the battle was fought, took place, that is still there. There is a railway station, Kurukṣetra. And that Kurukṣetra is still ''dharmakṣetra'', a religious place. People go for pilgrimage, and in the ''Vedas'' also it is stated that ''kuru-kṣetre dharma'' . . . (indistinct) . . . you perform religious rituals in Kurukṣetra. Therefore in the ''Bhagavad-gītā'' it is said, ''dharma-kṣetre kuru-kṣetre'' ([[BG 1.1 (1972)|BG 1.1]]). It is fact, historical fact. It is not imagination. But many commentators have taken as imagination, therefore they are misled. It is historical. | '''Prabhupāda:''' No. Battlefield, where the battle was fought, took place, that is still there. There is a railway station, Kurukṣetra. And that Kurukṣetra is still ''dharmakṣetra'', a religious place. People go for pilgrimage, and in the ''Vedas'' also it is stated that ''kuru-kṣetre dharma'' . . . (indistinct) . . . you perform religious rituals in Kurukṣetra. Therefore in the ''Bhagavad-gītā'' it is said, ''dharma-kṣetre kuru-kṣetre'' ([[BG 1.1 (1972)|BG 1.1]]). It is fact, historical fact. It is not imagination. But many commentators have taken as imagination, therefore they are misled. It is historical. | ||

Mensa Member: Well, will you . . . can you take the central road, Dr. Ware? | '''Mensa Member:''' Well, will you . . . can you take the central road, Dr. Ware? | ||

Dr. Ware: I would not need a road if I took it . . . (indistinct) . . . you have been very generous with your time | Dr. Ware: I would not need a road if I took it . . . (indistinct) . . . you have been very generous with your time | ||

| Line 575: | Line 575: | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, I'm sure there are other people who, I mean to say, wanted to have the opportunity discussing matters. | Dr. Ware: Well, I'm sure there are other people who, I mean to say, wanted to have the opportunity discussing matters. | ||

Mensa Member: Next time the Swami's in England, perhaps we can . . . Mensa members can . . . (indistinct) . . . in comparative religion could be . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' Next time the Swami's in England, perhaps we can . . . Mensa members can . . . (indistinct) . . . in comparative religion could be . . . | ||

Dr. Ware: Indeed, I think that would be very . . . and also it would be very interesting if you would care to take our test. | Dr. Ware: Indeed, I think that would be very . . . and also it would be very interesting if you would care to take our test. | ||

| Line 587: | Line 587: | ||

Dr. Ware: No. Just simple intelligence, that's all. | Dr. Ware: No. Just simple intelligence, that's all. | ||

Mensa Member: (indistinct) . . . an I.Q. test. | '''Mensa Member:''' (indistinct) . . . an I.Q. test. | ||

Dr. Ware: . . . that's all. Call it test, but it's something; we've got nothing better at the moment. | Dr. Ware: . . . that's all. Call it test, but it's something; we've got nothing better at the moment. | ||

| Line 611: | Line 611: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' There's a central premise that everything is simultaneously one and different. Just like flowers—there are many flowers, roses, but within the flowers there is variety. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' There's a central premise that everything is simultaneously one and different. Just like flowers—there are many flowers, roses, but within the flowers there is variety. | ||

Mensa Member: But still it raises the danger of another . . . (indistinct) . . . it really does. This is a very . . . (indistinct) . . . you're trying to make, but it's impossible to talk about physics in the language of chemistry. It's impossible. So when . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' But still it raises the danger of another . . . (indistinct) . . . it really does. This is a very . . . (indistinct) . . . you're trying to make, but it's impossible to talk about physics in the language of chemistry. It's impossible. So when . . . | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' So when he says there's a gradation, that we see gradation, that the soul is higher than the body, this is also . . . (indistinct) | '''Śyāmasundara:''' So when he says there's a gradation, that we see gradation, that the soul is higher than the body, this is also . . . (indistinct) | ||

| Line 619: | Line 619: | ||

Dr. Ware: Yes. But that is only because we've learned, I think, when we were small to look up to higher people . . . | Dr. Ware: Yes. But that is only because we've learned, I think, when we were small to look up to higher people . . . | ||

Mensa Member: (indistinct) . . . on each side of them and in the middle, on the other side, before and after . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' (indistinct) . . . on each side of them and in the middle, on the other side, before and after . . . | ||

Dr. Ware: This is the . . . you see, unconsciously you grow up with all these sort of prejudices, which are necessary. You've got to have some sort of time scale, you've got to have some sort of measuring scale, and therefore you tend to look up, and therefore you think highly of more important . . . (indistinct) . . . you talk about high position, you don't think of chaps sitting on the fence . . . | Dr. Ware: This is the . . . you see, unconsciously you grow up with all these sort of prejudices, which are necessary. You've got to have some sort of time scale, you've got to have some sort of measuring scale, and therefore you tend to look up, and therefore you think highly of more important . . . (indistinct) . . . you talk about high position, you don't think of chaps sitting on the fence . . . | ||

| Line 639: | Line 639: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' . . . beautiful. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' . . . beautiful. | ||

Mensa Member: (indistinct) . . . be subjective . . . (indistinct) | '''Mensa Member:''' (indistinct) . . . be subjective . . . (indistinct) | ||

Dr. Ware: And you see, a lot of people would like a red rose, because that has a symbolism to it. Why have a yellow rose? It must have a sort of subjective reaction. It has nothing to do with the fact that it's got a chromatic wavelength. | Dr. Ware: And you see, a lot of people would like a red rose, because that has a symbolism to it. Why have a yellow rose? It must have a sort of subjective reaction. It has nothing to do with the fact that it's got a chromatic wavelength. | ||

| Line 651: | Line 651: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Well, if you say like that, the majority of living entities, they are eating without this knowledge of enzyme and other things. So if you take votes, the votes are greater. Just like human being, a few human beings are interested in analyzing this enzyme. And the human beings are very small quantity. There are 8,400,000 species of life. They're eating with a natural way, and they're quite healthy. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Well, if you say like that, the majority of living entities, they are eating without this knowledge of enzyme and other things. So if you take votes, the votes are greater. Just like human being, a few human beings are interested in analyzing this enzyme. And the human beings are very small quantity. There are 8,400,000 species of life. They're eating with a natural way, and they're quite healthy. | ||

Mensa Member: Knowledge of the process is comparatively important. If you want to enjoy it more you don't have to know about enzymes and proteins, you have to know about the right sort of wine and the . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' Knowledge of the process is comparatively important. If you want to enjoy it more you don't have to know about enzymes and proteins, you have to know about the right sort of wine and the . . . | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' Enjoyment is the standard. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' Enjoyment is the standard. | ||

| Line 667: | Line 667: | ||

Dr. Ware: We've got them, but we kill them. | Dr. Ware: We've got them, but we kill them. | ||

Mensa Member: . . . another analogy. | '''Mensa Member:''' . . . another analogy. | ||

Dr. Ware: Exactly. This is the trouble. It's unwise . . . if you could accept the concept as a whole, there's no need to try and give an analogy. | Dr. Ware: Exactly. This is the trouble. It's unwise . . . if you could accept the concept as a whole, there's no need to try and give an analogy. | ||

Mensa Member: I don't accept your, um . . . the point you were making when you began that analogy, I think, was that people that do look for spiritual knowledge, in quotes, um, it would appear there was something wrong with them. | '''Mensa Member:''' I don't accept your, um . . . the point you were making when you began that analogy, I think, was that people that do look for spiritual knowledge, in quotes, um, it would appear there was something wrong with them. | ||

Dr. Ware: No, no, not always. I say there are some people who obviously . . . if they have to look for it, they haven't got it. The people who've got it don't need to look for it. | Dr. Ware: No, no, not always. I say there are some people who obviously . . . if they have to look for it, they haven't got it. The people who've got it don't need to look for it. | ||

Mensa Member: Yeah. Resorting to the accursed thing again, some people go to the doctor that are sick and some people aren't sick, are hypochondriacs. | '''Mensa Member:''' Yeah. Resorting to the accursed thing again, some people go to the doctor that are sick and some people aren't sick, are hypochondriacs. | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' It's just like if someone points out to you, for instance, that this material world is based upon sense gratification and everyone is striving to gratify the impulse of their senses, that's a verbalization of a truth which is not apparent in any other way, or it's very difficult to find out in any other way. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' It's just like if someone points out to you, for instance, that this material world is based upon sense gratification and everyone is striving to gratify the impulse of their senses, that's a verbalization of a truth which is not apparent in any other way, or it's very difficult to find out in any other way. | ||

| Line 693: | Line 693: | ||

Dr. Ware: Because of this feeling of wanting to know. | Dr. Ware: Because of this feeling of wanting to know. | ||

Mensa Member: I wonder what . . . (indistinct) | '''Mensa Member:''' I wonder what . . . (indistinct) | ||

Dr. Ware: No, no, they've made the observation. I don't think they have the power to . . . | Dr. Ware: No, no, they've made the observation. I don't think they have the power to . . . | ||

| Line 715: | Line 715: | ||

Dr. Ware: In the same way, how can you satisfy a person's lack of emotional content in his job by giving him more money? Half of the trouble starts with the jobs. They have no emotive content now because there's no rapport between them and their boss. They have practically no intellectual interest because they have a routine job in a factory. And you know they are really deprived in this sad way. | Dr. Ware: In the same way, how can you satisfy a person's lack of emotional content in his job by giving him more money? Half of the trouble starts with the jobs. They have no emotive content now because there's no rapport between them and their boss. They have practically no intellectual interest because they have a routine job in a factory. And you know they are really deprived in this sad way. | ||

Mensa Member: Then what worries lots of people about lots of religions is the . . . (indistinct) . . . for example of pointing a finger at the moon and choosing the finger with the moon. | '''Mensa Member:''' Then what worries lots of people about lots of religions is the . . . (indistinct) . . . for example of pointing a finger at the moon and choosing the finger with the moon. | ||

Dr. Ware: One of the difficulties, and I think this is true when I was saying simple people, using that in its broader sense, some people cannot get anything at all unless they have a little picture. You know, it helps them; not like the dear old lady who found . . . | Dr. Ware: One of the difficulties, and I think this is true when I was saying simple people, using that in its broader sense, some people cannot get anything at all unless they have a little picture. You know, it helps them; not like the dear old lady who found . . . | ||

| Line 725: | Line 725: | ||

Dr. Ware: Ah, yes. Now parable is better than analogy. An analogy is an intellectual thing, whereas a parable is a human thing. It's got a warmth in it. It's in three dimensions, not a cross-section. And he was, of course, awfully clever at choosing them. | Dr. Ware: Ah, yes. Now parable is better than analogy. An analogy is an intellectual thing, whereas a parable is a human thing. It's got a warmth in it. It's in three dimensions, not a cross-section. And he was, of course, awfully clever at choosing them. | ||

Mensa Member: I don't think your friend Christmas Humphreys will agree with either of those statements. | '''Mensa Member:''' I don't think your friend Christmas Humphreys will agree with either of those statements. | ||

Dr. Ware: Knowing him very well, I don't . . . one would be surprised at . . . (indistinct) . . . he would be perfectly happy to feel that I was disagreeing with him. I think he confuses himself with Kṛṣṇa at times. | Dr. Ware: Knowing him very well, I don't . . . one would be surprised at . . . (indistinct) . . . he would be perfectly happy to feel that I was disagreeing with him. I think he confuses himself with Kṛṣṇa at times. | ||

Mensa Member: Well, is that absolutely . . . (indistinct) . . .? | '''Mensa Member:''' Well, is that absolutely . . . (indistinct) . . .? | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' The Buddhist thinks that everyone is God? | '''Śyāmasundara:''' The Buddhist thinks that everyone is God? | ||

| Line 791: | Line 791: | ||

Dr. Ware: That is most impressive, that giving up those things which are really . . . if they were inessentials it would be good to give them up, but since they are harmful, it's even more beneficial. How that can be achieved in the modern world is quite a remarkable feat. | Dr. Ware: That is most impressive, that giving up those things which are really . . . if they were inessentials it would be good to give them up, but since they are harmful, it's even more beneficial. How that can be achieved in the modern world is quite a remarkable feat. | ||

Mensa Member: Would you say that you agree with the Swami the . . . some of the bases of religion are essential, are therapeutically useful, valid? | '''Mensa Member:''' Would you say that you agree with the Swami the . . . some of the bases of religion are essential, are therapeutically useful, valid? | ||

Dr. Ware: I think, again, it depends upon the person. I should say to lots of people they are essential, or you might even go farther, as Jung would say, that to everybody they are essential, but they mean something different to different types of people from the very . . . (indistinct) . . . and from the long hair to the very abstract. But the people who lack it do seem to lack. It's rather like they lack a gyroscope. They've got no stability. They just sort of wobble all over the place. | Dr. Ware: I think, again, it depends upon the person. I should say to lots of people they are essential, or you might even go farther, as Jung would say, that to everybody they are essential, but they mean something different to different types of people from the very . . . (indistinct) . . . and from the long hair to the very abstract. But the people who lack it do seem to lack. It's rather like they lack a gyroscope. They've got no stability. They just sort of wobble all over the place. | ||

Mensa Member: No, they don't. One . . . (indistinct) . . . scientific truth is this works. | '''Mensa Member:''' No, they don't. One . . . (indistinct) . . . scientific truth is this works. | ||

Dr. Ware: I would like to put my own view, is that I believe very much in the Christian ethics, and I could believe in Kṛṣṇa ethics, or, if I might say. But I could also believe in that without the need to believe in Kṛṣṇa or God. Now whether that's a delusion on my part, and I really do believe deep down inside me, and I don't know . . . | Dr. Ware: I would like to put my own view, is that I believe very much in the Christian ethics, and I could believe in Kṛṣṇa ethics, or, if I might say. But I could also believe in that without the need to believe in Kṛṣṇa or God. Now whether that's a delusion on my part, and I really do believe deep down inside me, and I don't know . . . | ||

| Line 807: | Line 807: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' One priest in Boston, he issued leaflet regretting that these boys—he saw our students—he appreciated that, "These boys are so much after God, and they're our boys. We could not give them." Actually the same boy was, one year or two years ago, he was not going to church, he had no interest in God consciousness, but now this same boy is mad after God. And he's twenty-four hours in God consciousness. They're chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa ''mantra'' twenty-four hours. How they have become so . . . | '''Prabhupāda:''' One priest in Boston, he issued leaflet regretting that these boys—he saw our students—he appreciated that, "These boys are so much after God, and they're our boys. We could not give them." Actually the same boy was, one year or two years ago, he was not going to church, he had no interest in God consciousness, but now this same boy is mad after God. And he's twenty-four hours in God consciousness. They're chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa ''mantra'' twenty-four hours. How they have become so . . . | ||

Mensa Member: The Swami made a good point when I talked to him the other day that some of the American churches are packed. There's a great swing towards religion in America, and they're getting a lot of humbug, you know, which is, just one of those . . . I think I disagree with you that today theology has lost its status with the . . . (indistinct) . . . of science, but there seems to be a swing, in my little world, towards spiritual things. | '''Mensa Member:''' The Swami made a good point when I talked to him the other day that some of the American churches are packed. There's a great swing towards religion in America, and they're getting a lot of humbug, you know, which is, just one of those . . . I think I disagree with you that today theology has lost its status with the . . . (indistinct) . . . of science, but there seems to be a swing, in my little world, towards spiritual things. | ||

Dr. Ware: Oh, I'm glad to hear that because, as I say, one's been watching the swing the other way. Coming back to your point, the other vital thing, we said that earlier on, that we still don't know, in other words, in order to get spiritual qualities you've got to have silence. Correspondingly, in the modern world we have this neurotic disease, the desire for noise. These people can't even do a job without having a transistor set on. There's something psychopathic about this. | Dr. Ware: Oh, I'm glad to hear that because, as I say, one's been watching the swing the other way. Coming back to your point, the other vital thing, we said that earlier on, that we still don't know, in other words, in order to get spiritual qualities you've got to have silence. Correspondingly, in the modern world we have this neurotic disease, the desire for noise. These people can't even do a job without having a transistor set on. There's something psychopathic about this. | ||

Mensa Member: It can be used though, can't it? The Kṛṣṇa people use it, the concept of using the word "Kṛṣṇa" . . . (indistinct) . . . the ears, the most subtle of the senses . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' It can be used though, can't it? The Kṛṣṇa people use it, the concept of using the word "Kṛṣṇa" . . . (indistinct) . . . the ears, the most subtle of the senses . . . | ||

Dr. Ware: Yes, but this "boop-a-doop" noise they have, the language stops you from doing your work properly. | Dr. Ware: Yes, but this "boop-a-doop" noise they have, the language stops you from doing your work properly. | ||

| Line 825: | Line 825: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' In Revelations, I don't remember the exact verse, "Strike the . . . (indistinct)" | '''Śyāmasundara:''' In Revelations, I don't remember the exact verse, "Strike the . . . (indistinct)" | ||

Mensa Member: The only spiritual sensation for many people, really, it's from music. | '''Mensa Member:''' The only spiritual sensation for many people, really, it's from music. | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' Silence is defined in ''Bhagavad-gītā'' as speaking about Kṛṣṇa, or hearing Kṛṣṇa's name. That is silence. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' Silence is defined in ''Bhagavad-gītā'' as speaking about Kṛṣṇa, or hearing Kṛṣṇa's name. That is silence. | ||

| Line 859: | Line 859: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' That is for the voidist, not for the spiritualist. The spiritual life there is enough activities for even scientists. That they do not know. They mean spiritual life mean void. That is negation of the present activities only, negative idea. But actually, when you stop material activities your real activity begins. That is spiritual life. The spirit, spirit soul, is active. You cannot stop it. You cannot stop it. Now it is acting through these coverings of material, matter, therefore it is imperfect activities. But if the activity is uncovered by material things, that is real activity. | '''Prabhupāda:''' That is for the voidist, not for the spiritualist. The spiritual life there is enough activities for even scientists. That they do not know. They mean spiritual life mean void. That is negation of the present activities only, negative idea. But actually, when you stop material activities your real activity begins. That is spiritual life. The spirit, spirit soul, is active. You cannot stop it. You cannot stop it. Now it is acting through these coverings of material, matter, therefore it is imperfect activities. But if the activity is uncovered by material things, that is real activity. | ||

Mensa Member: But aren't desires biological in cause? | '''Mensa Member:''' But aren't desires biological in cause? | ||

Dr. Ware: They're necessary. | Dr. Ware: They're necessary. | ||

Mensa Member: Yes, but they're biologically necessary rather than spiritually necessary. | '''Mensa Member:''' Yes, but they're biologically necessary rather than spiritually necessary. | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, may I say, let's go farther, that when you say biologically necessary, is it necessary for you to be alive? What scientific . . . | Dr. Ware: Well, may I say, let's go farther, that when you say biologically necessary, is it necessary for you to be alive? What scientific . . . | ||

| Line 873: | Line 873: | ||

Dr. Ware: But I think you need . . . I agree, I would say you need both. I want spiritual life, material life. | Dr. Ware: But I think you need . . . I agree, I would say you need both. I want spiritual life, material life. | ||

Mensa Member: (indistinct) . . . spiritual thing, I mean, isn't it like people talking about China or New York . . . (indistinct) . . . about it, in fact it might even be a little . . . (indistinct) | '''Mensa Member:''' (indistinct) . . . spiritual thing, I mean, isn't it like people talking about China or New York . . . (indistinct) . . . about it, in fact it might even be a little . . . (indistinct) | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, I think to each person his picture is different, too. | Dr. Ware: Well, I think to each person his picture is different, too. | ||

| Line 905: | Line 905: | ||

Dr. Ware: I fear, Swami, if I may say so, without disrespect, that in some ways you're preaching to the converted, and you only make it more muddled to me by giving analogies. Don't you feel that at times? | Dr. Ware: I fear, Swami, if I may say so, without disrespect, that in some ways you're preaching to the converted, and you only make it more muddled to me by giving analogies. Don't you feel that at times? | ||

Mensa Member: Yeah, I think the Swami's used to . . . probably used to talking to people that need this . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' Yeah, I think the Swami's used to . . . probably used to talking to people that need this . . . | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' Never mind the method. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' Never mind the method. | ||

| Line 945: | Line 945: | ||

Dr. Ware: But it helps some people. | Dr. Ware: But it helps some people. | ||

Mensa Member: The soul is a very interesting concept, the soul as well, the fact that the soul is quantifiable, that it exists in a smaller part in the larger animals, and a higher part in a higher animals. | '''Mensa Member:''' The soul is a very interesting concept, the soul as well, the fact that the soul is quantifiable, that it exists in a smaller part in the larger animals, and a higher part in a higher animals. | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' No. It's the same size in all entities. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' No. It's the same size in all entities. | ||

Mensa Member: Oh, it is, is it? But when we reach a point when we don't know whether there are living things or not, you know, the amino acids, and things like that or . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' Oh, it is, is it? But when we reach a point when we don't know whether there are living things or not, you know, the amino acids, and things like that or . . . | ||

Dr. Ware: Well, I would take up that straight away, fundamentally, that it's perfectly correct to say it's the same size every . . . (indistinct) . . . has no size. | Dr. Ware: Well, I would take up that straight away, fundamentally, that it's perfectly correct to say it's the same size every . . . (indistinct) . . . has no size. | ||

| Line 967: | Line 967: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Then find out the soul, if you have got instrument. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Then find out the soul, if you have got instrument. | ||

Mensa Member: How many angels on the end of a pin? | '''Mensa Member:''' How many angels on the end of a pin? | ||

Dr. Ware: In fact this is coming back to that . . . the analogy again. | Dr. Ware: In fact this is coming back to that . . . the analogy again. | ||

Mensa Member: But the whole thing is so . . . (indistinct) . . . about this . . . (indistinct) . . . putting in Kṛṣṇa instead of Christ. | '''Mensa Member:''' But the whole thing is so . . . (indistinct) . . . about this . . . (indistinct) . . . putting in Kṛṣṇa instead of Christ. | ||

Dr. Ware: But the whole business, if you try to explain . . . | Dr. Ware: But the whole business, if you try to explain . . . | ||

| Line 979: | Line 979: | ||

Dr. Ware: Ah, but the mathematician would say that that isn't . . . the definition of a point is something that has no breadth or depth, but his purpose is working out his philosophy. | Dr. Ware: Ah, but the mathematician would say that that isn't . . . the definition of a point is something that has no breadth or depth, but his purpose is working out his philosophy. | ||

Mensa Member: (indistinct) . . . he'd say something entirely different. They'd say that the absolute point . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' (indistinct) . . . he'd say something entirely different. They'd say that the absolute point . . . | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' But if you magnify the point, you'll find there is . . . | '''Prabhupāda:''' But if you magnify the point, you'll find there is . . . | ||

| Line 1,019: | Line 1,019: | ||

Dr. Ware: Well you won't get very far in any form of philosophy in . . . (indistinct) . . . language. | Dr. Ware: Well you won't get very far in any form of philosophy in . . . (indistinct) . . . language. | ||

Mensa Member: . . . (indistinct) | '''Mensa Member:''' . . . (indistinct) | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' But the consciousness in which something is done denotes it. For instance, I could be sweeping the street. Someone would think, "Ah, I'm just a material street sweeper." But if I'm doing it for Kṛṣṇa, it's a transcendental activity, it's a spiritual activity, not a material activity. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' But the consciousness in which something is done denotes it. For instance, I could be sweeping the street. Someone would think, "Ah, I'm just a material street sweeper." But if I'm doing it for Kṛṣṇa, it's a transcendental activity, it's a spiritual activity, not a material activity. | ||

| Line 1,073: | Line 1,073: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Light and heat, you cannot think of without fire. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Light and heat, you cannot think of without fire. | ||

Mensa Member: Fluorescence, certain chemicals. | '''Mensa Member:''' Fluorescence, certain chemicals. | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' The origin is . . . | '''Śyāmasundara:''' The origin is . . . | ||

| Line 1,081: | Line 1,081: | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' There is no light, no heat without fire. That's a fact. | '''Prabhupāda:''' There is no light, no heat without fire. That's a fact. | ||

Mensa Member: Everybody . . . (indistinct) . . . I think. | '''Mensa Member:''' Everybody . . . (indistinct) . . . I think. | ||

Dr. Ware: Yeah, you see, that's the trouble. You can say really that there's no light or heat without an electrical movement. That's as far as you need. You don't need to go any farther. | Dr. Ware: Yeah, you see, that's the trouble. You can say really that there's no light or heat without an electrical movement. That's as far as you need. You don't need to go any farther. | ||

Mensa Member: No, the point you were making is that the absolute source of everything is the sun. Was that the . . .? | '''Mensa Member:''' No, the point you were making is that the absolute source of everything is the sun. Was that the . . .? | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' That is heat. That is fire. | '''Prabhupāda:''' That is heat. That is fire. | ||

Mensa Member: Even if it's not there now, it was there a thousand years ago. | '''Mensa Member:''' Even if it's not there now, it was there a thousand years ago. | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' It's gone through about the different transformations from its original source. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' It's gone through about the different transformations from its original source. | ||

| Line 1,101: | Line 1,101: | ||

Dr. Ware: Most interesting . . . (indistinct) | Dr. Ware: Most interesting . . . (indistinct) | ||

Mensa Member: Yes, but it all . . . (indistinct) . . . great argument. | '''Mensa Member:''' Yes, but it all . . . (indistinct) . . . great argument. | ||

'''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. We shall talk more when we meet next. | '''Prabhupāda:''' Yes. We shall talk more when we meet next. | ||

| Line 1,113: | Line 1,113: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' We went walking there one morning, Lincoln's Inn. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' We went walking there one morning, Lincoln's Inn. | ||

Mensa Member: . . . (indistinct) | '''Mensa Member:''' . . . (indistinct) | ||

Dr. Ware: Yes. I've always wanted to go there. We've got four Tibetans over, studying . . . (indistinct) . . . part of the college estate of Hampstead. And I've always liked the idea of their going up into those wonderful mountains and . . . | Dr. Ware: Yes. I've always wanted to go there. We've got four Tibetans over, studying . . . (indistinct) . . . part of the college estate of Hampstead. And I've always liked the idea of their going up into those wonderful mountains and . . . | ||

| Line 1,125: | Line 1,125: | ||

'''Śyāmasundara:''' Perfect diet. | '''Śyāmasundara:''' Perfect diet. | ||

Mensa Member: Thank you for sparing this time and . . . | '''Mensa Member:''' Thank you for sparing this time and . . . | ||

Dr. Ware: Such short notice, I didn't realize . . . it was such a pleasure, and I was so glad that you were able to fit it in before you go. | Dr. Ware: Such short notice, I didn't realize . . . it was such a pleasure, and I was so glad that you were able to fit it in before you go. | ||

Revision as of 03:23, 31 August 2023

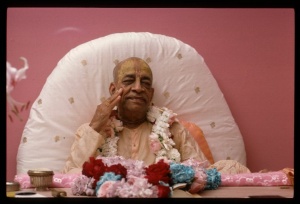

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

(Conversation with Dr. Weir of the Mensa Society)

(The following italic text was not recorded but was written on the reel box before recorder was switched on)

Dr. Ware: Swāmījī, you'll be glad to know your Society, like ours, is worldwide and not based upon color, creed or designations.

Prabhupāda: Yes, designation means falsely identifying that I am this body.

Prabhupāda: So now the soul is in this body. Next time, the soul will be in another body. So according to the body we are having designations. As soon as we get American body, I . . .

(break) . . . designation. According to the body I create my designation. But one has to become free from all designation. That is called liberated stage—in his own constitutional position. That position is eternal servant of God. That is the real position of every living entity.

But because at the present moment the living entity is in contact with matter, so according to the material mode of the body, he's identifying himself with this body. That is called material designation, "I am American," "I am Englishman," "I am Hindu," "I am Muslim," "I am this," "I am that"—these are all designation. So real perfection of life is without designation. And that is the real, constitutional position. Jīvera svarūpa haya nitya-kṛṣṇa-dāsa (CC Madhya 20.108-109). Actual position of the living entity it is (indistinct—microphone feedback problem) Don't disturb, let it go . . . (indistinct)

So that is the perfection of life. And human life is especially meant for . . . to come to that transcendental position, without any designation. Our Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement is for that purpose. One should be always thinking of Kṛṣṇa, or God. That position is perfect position. And if one keeps himself in that designationless position, always thinking of himself as part and parcel of God, then next life he goes back home, back to Godhead. Tyaktvā dehaṁ punar janma naiti (BG 4.9). After quitting this body he does not come back again to take another material body. He takes spiritual body, or develops a spiritual body, and goes back to home, back to Godhead, which means eternal, blissful life of knowledge.

Our this Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement is for that purpose. We are trying to bring all men—of different dimensions, different division—to come to this position, always thinking of that, "I am part and parcel of God. My real position is to serve God." Just like this finger is part and parcel of my body. The business of the finger is to serve the body. So long it is in normal condition, the finger is meant for serving the body. When the finger is painful, or in abnormal condition, it cannot serve the body. Similarly, the living entity, being part and parcel of God, when we cannot serve God, that is his abnormal condition. And when he serves God, that is his normal condition. That is designationless position. That is our program.

Dr. Ware: That's very interesting. To my mind the nearest approach in the Christian religion is the Unitarian position, which I don't know if you have studied.

Prabhupāda: Christian religion is practically . . . from the name it appears, Christian and "Kṛṣṇian." Original word of this "Christ" comes from the Greek word "Christo."

Dr. Ware: "Anointed."

Prabhupāda: Huh?

Dr. Ware: "Anointed."

Prabhupāda: Yes. This "Christa" is Kṛṣṇa.

Dr. Ware: From the Sanskrit?

Prabhupāda: Yes. Kṛṣṭa is the popular word for Kṛṣṇa. And Kṛṣṇa is always anointed with tilaka. We follow this tilaka, Kṛṣṇa, anointed with the sandal pulp. So, so far I think, there is some very nearest relationship with this Christian and "Kṛṣṇian". Kṛṣṭa means love, love of Godhead, or love. We are preaching also the same philosophy. Try to . . . not try, the love of Kṛṣṇa is there in everyone's heart, but it is covered. And being covered, it is misplaced.

We are loving our society, loving this body, loving our family, loving our kinsmen or loving internationally human society. But this love is actually perverted reflection of real love of God. Because the love is not placed in the real place, therefore we are being frustrated in love. Just like in our country Mahatma Gandhi, he loved his country very much. But at the last moment the countrymen shot him down. He was shot down by his own countrymen. The love was paid by shooting him, and he lost his life. There are many instances.

Dr. Ware: Socrates, Christ. Plenty.

Prabhupāda: Yes. So here, the love propensity is being misplaced in this material world. That should be placed in God. Then the love will be perfection. Just like if you pour water on the leaves of the tree or branches of the tree, it is simply a waste of time. If you pour water on the root, then the effect of pouring water is distributed. Similarly, foodstuff, if you place the foodstuff on your nose, on your eyes or your ears, it is simply wasted. But if you put foodstuff to the mouth in the stomach, immediately the energy derived from the foodstuff is distributed throughout the whole body. Similarly, if you love God then your . . . automatically your love is distributed to everyone, every entity.

But if you don't love, if you simply love your country . . . just like an Englishman, you love your country; German, he loves his country, but there is fight between the English and the Germans because the love is misplaced. But if the Germans or the Englishmen or the Indians, they put their love in God, there will be no more fighting.

Therefore our philosophy is to educate people how to love God. That is real religion. Sa vai puṁsāṁ paro dharmo yato bhaktir adhokṣaje (SB 1.2.6). That is first-class religion which teaches the follower how to love God. And as soon he becomes a lover of God . . . just like I am Indian, but I have come to Western country to teach love of God. It is not that I am satisfied only in myself that, "I love God—that's all right," but due to my love to God I love others also, because I am trying to teach them to love God. The same philosophy. So if people take seriously this movement, how to love God, then human society will be perfect.

Dr. Ware: May I suggest you've already made one contribution from India, which is almost the antithesis, and corroborate your suggestion about pouring water on the root. We do get leaves from India. We pour water on them, and we make that delicious drink, tea, which is one of those drinks which are used for inculcating the brotherhood of man.

Prabhupāda: That's all right. But do you think it is natural to pour water on the leaves?

Dr. Ware: Well, why not then? That for leaves, water's natural.

Prabhupāda: No. You practically you see it is—water on the leave, but you don't water on the root, it will dry up. If you put food on your nose, on your eyes, the eyes will be blind and the nostril will be suffocated. But if you put in the proper place, in the stomach, the energy will be distributed.

Dr. Ware: You know that's just an analogy.

Prabhupāda: Yes. This is natural. Similarly, if God is the root of everything, as we understand from Vedānta-sūtra . . . God means the original root of everything: janmādy asya yataḥ (SB 1.1.1). The description of Absolute Truth, or God, is there in the Vedānta-sūtra. That first aphorism is, "What is God?" Athāto brahma jijñāsā—inquiry about God. The next aphorism is, "God is that which is the root of everything, from which everything emanates." That is the perfect definition of God, "the origin of everything." So the same example in God, that the root is the origin of the whole tree.

Dr. Ware: The seed is the origin of the whole tree, if I may say.

Prabhupāda: How you can be origin, because you are the effect?

Śyāmasundara: The seed.

Prabhupāda: Huh?

Śyāmasundara: The seed.

Prabhupāda: The seed. Yes, seed. The seed is described in the Bhagavad-gītā, bījo 'haṁ sarva-bhūtānām (BG 7.10): "Everything that is living, the root, or the seed, I am." God says. The seed is God. Bījo 'haṁ sarva-bhūtānām. Just like the rose tree, it has got a seed, but where from this seed comes?

(guests entering room) Come on. Hare Kṛṣṇa . . . (indistinct) . . . give him another . . . (indistinct)

Seed, original seed is God. Your theory of seed is very nice, but the original seed of everything is God, the cause of all causes. In the Brahma-saṁhitā it is said:

- īśvaraḥ paramaḥ kṛṣṇaḥ

- sac-cid-ānanda vigrahaḥ

- anādir ādir govindaḥ

- sarva-kāraṇa-kāraṇam

- (Bs. 5.1)

Kāraṇam. Kāraṇa means cause, cause of all causes, seed of all seeds. There are different seeds.

Dr. Ware: Causa causam.

Prabhupāda: Ah, cause of all causes.

Śyāmasundara: That's Latin?

Dr. Ware: Yes.

Śyāmasundara: It's similar.

Prabhupāda: What is that?

Dr. Ware: A Latin legal phrase: causa causam, the cause of the cause.

Prabhupāda: I see. So God is cause of all causes. And in the Bhagavad-gītā it is explicitly said:

- ahaṁ sarvasya prabhavo

- mattaḥ sarvaṁ pravartate

- iti matvā bhajante māṁ

- budhā bhāva-samanvitāḥ

- (BG 10.8)

"I am the original source of everything. Everything is emanating from Me." Iti matvā, "understanding like this," budhā. Budhā means those who are conversant, thoroughly in knowledge. Iti matvā bhajante māṁ budhā bhāva samanvitāḥ, in ecstasy, "Oh, here is the original cause of all causes."

So in this way those who are advanced in knowledge, budhā, they engage themself in the service of the original cause of all causes. He's the cause of all causes, but He has no cause. That is God. Anādir ādir govindam. He has no cause, but He's the cause of all life. That is God. Just like I am the effect; my father is the cause. Similarly, my grandfather is the cause of my father. My grandfather is the effect of the cause great-grandfather. You go on searching out, searching out. So when you find out the original cause, that is God. That is the definition of God.

Mensa Member: Do you . . . (indistinct) . . . prime mover argument is who is the prime mover? What is the logical necessity for a first cause? Would you agree with that?

Dr. Ware: Well, I think it's inherent in your definition of something that's omnipotent that it's very like saying it's necessary to have no beginning in order to have no end. It's really a concept. Whether it exists or not it doesn't matter.

Mensa Member: Yes. Then even negatives imply limitation. If something has only positive attributes, it's limited if you exclude negative attributes. Or is that just a . . .

Dr. Ware: Well no, if something has all attributes, we only cause, or call them to be caused, positive or negative because we have a tendency to want to think in terms of dichotomies, "good" and "bad," whereas really, if you're a scientist, you say: "This exists." It's only when morals come in, you say some things are good and some things are bad, and you start making antinomies. Really, your Godhead would contain all those things, and to Him there's no such thing as good or evil, but to Him they are all of value. It's man who saw the good and evil.

Mensa Member: I wasn't particularly thinking of the good and evil value. I was simply thinking of negative attributes.

Dr. Ware: Well, I'm sorry, I don't know quite what you mean. Unless you define the negative attribute, I'm not quite sure what it is.

Mensa Member: Not beginning.

Dr. Ware: Well that, with respect, I think, doesn't really follow, because there're some things that don't have opposites or negatives, although (in) nature. This is what I say, that there are certain categories of things to which if somebody says: "Now what's the opposite of that?" you'd have to say: "There isn't an opposite," because it isn't the sort of thing to have an opposite.

Mensa Member: So you wouldn't accept the prime mover either?

Dr. Ware: Well, it's not an argument; it's a postulate. I don't accept it. I mean, you have to accept it if you're going to . . . you know the total . . . (indistinct) . . . so to speak. You can't have it half way.

Prabhupāda: This word "positive" and "negative" . . . just like the sun—the backside is the negative and the front side is the positive, light and darkness.

Dr. Ware: Well the sun doesn't have a backside of darkness. It's light all round.

Prabhupāda: I mean to say, in relationship with the sun, the planet, the planet in the front side there is light. In the backside there is darkness. But the darkness is the effect of the light. Where the light is absent there is darkness.

Dr. Ware: Only to an observer. If there's no observer there, there's no difference between light and dark.

Prabhupāda: No, this is the actual position. Just like this is sun, but this side is light, this side is darkness. So light and darkness, two opposite elements. But it is due to the same cause. Absence of light is darkness, and presence of light is light.

Dr. Ware: Or I say there are some things that have those dichotomies and others don't.

Prabhupāda: So actually the cause is one, but in different position, one side is light, one side is darkness. Therefore the cause cannot be different. The cause is one. But under different position it appears, "This is light," "This is darkness." So bad, which you consider bad, that is also caused by the Supreme Cause. In the Supreme there is no good or bad. Everything is absolute. Just like the sun is always light, but, in relationship with sun, the planets, one side is dark, one side is light. So black means that is also caused by the light, absence of light—that is black, dark.

Dr. Ware: With respect, it's not caused by the light. It's the absence of light.

Prabhupāda: Absence, that I'm saying. It is also, indirectly, the cause is the light.

Dr. Ware: No, because your illustration you gave of the light of the sun falling on one side and making that light and the other side dark, but you can also have a body which is in the complete absence of any light anyway, so there won't be any differentiation.

Prabhupāda: No. There is light. The light is now visible. Light is there. Just like we say that our relationship with God is there. One is conscious; another is unconscious. Otherwise, God consciousness is there. Therefore any process that awakens that consciousness, that is perfect process. The consciousness is there. That is stated in Caitanya-caritāmṛta, an authorized book.

Nitya siddha kṛṣṇa bhakti sādhya kabhu naya (CC Madhya 22.107). This God consciousness is not something artificial. The God consciousness is there. Just like these European boys and girls, they're now devotees of Kṛṣṇa. Not that artificially we have imposed this Kṛṣṇa consciousness. The Kṛṣṇa consciousness was there. By . . . under certain process of treatment that has been awakened.

Dr. Ware: That's why I think it's better to accept that as it is, rather than make analogies, which are dangerous.

Prabhupāda: I may make analogy or not analogy, but the thing is that Kṛṣṇa consciousness is there, but it is covered. As soon as its covering is taken away—it is uncovered—the original position comes out.

Śyāmasundara: I believe he made one observation which is rather in the British tradition, I believe, where he said that if there was no observer, then there would be no such thing as light and darkness.

Dr. Ware: Yes, light and dark are subjective reactions. Really, the scientists would say there are wave lengths of a certain type in one part of the universe and in the other they're absent. But until you have an observer, you can't notice that.

Mensa Member: But the planet would still be there . . . (indistinct)

Dr. Ware: Well, Samuel Johnson quite rightly refuted that by taking . . . (indistinct)

Prabhupāda: Actually, there is no darkness. Take it sun as, it is whole. There is no darkness and everything is in sunshine. All the planets, they are rotating in sunshine. So under certain condition, one part is becoming dark, another part is light. But actually the whole universe is full with sunshine. Sarvaṁ khalv idaṁ brahma (Chāndogya Upaniṣad 3.14.1). That is the exact definition given in Sanskrit: everything is light, brahma.

Mensa Member: That's another postulate.

Dr. Ware: You can build any theory according to the number of postulates you're willing to accept which cannot be analyzed, including the basis of science, that the atom, as originally thought of by Theocritus and others, is this thing that you cannot go beyond and cap down . . . (indistinct) . . . and saying with your philosophy or your theology that you go down until you can find nothing, except that you say that causa causam, and then you build back again from that. But that's what I was saying earlier on: the . . . (indistinct) . . . is very close to the Unitarian position in Christianity.

Prabhupāda: Yes.

Dr. Ware: Far more acceptable to every type of Christian than any of the specific creeds or sects, you know, the Church of England, Anglicans, Roman Catholics, every other form of prophecy. And you have that greater universality . . . (indistinct) . . . and you've got Tibetans who will accept your basis in the same way as a Westerner could.

Prabhupāda: What is that?

Dr. Ware: A Tibetan could accept your position.

Prabhupāda: Tiberian? Tibetians? What is their philosophy?

Dr. Ware: You've heard of the Dalai Lama?

Prabhupāda: Yes. What does he say?

Dr. Ware: Well, his position would be the same as yours, wouldn't it? In religion?

Mensa Member: You mean the Tibetan Buddhist attitude towards the Godhead is the same as the Kṛṣṇas?

Dr. Ware: Yes. They have that same basis.

Prabhupāda: But so far we know, that Buddhists, they do not believe in God, existence of God.

Dr. Ware: No. They believe in this existence of a "Goddess" if you like.

Mensa Member: It's very subjective. The Buddhist point of view in general seems to be very much that of the nineteenth century English rationalist, the agnostic, in its visual sense.

Dr. Ware: That's why I say the Unitarian comes closest to it.

Śyāmasundara: What is that?

Mensa Member: Well, the fact that a Godhead is . . . is impossible to comprehend. It maybe or may not be in very brief terms.

Dr. Ware: But if you accept its existence, then it's present in everybody. Which is exactly what you're saying. Whether they utilize it, whether, as you call it, uncovered, or to the degree of which they are conscious of it, is a different thing.

Prabhupāda: Yes. It is a question of consciousness, development of consciousness.

Dr. Ware: That's where your line, I think, is so very good in saying that the real evolution of man's mind has been his ability to produce more and more of the functions of whatever the mind may be. But the mind is just as indefinable as God. We know what the brain is, but we don't know what the mind is. Yet more and more of it under conscious control instead of being irrationally eruptive.

Prabhupāda: But there is a summum bonum of that realization. That is explained in Bhagavad-gītā: bahūnāṁ janmanām ante, jñānavān māṁ prapadyate (BG 7.19). After many, many births of this mental evolutionary process, when actually he becomes wise, he becomes God conscious and surrenders to God. That is real evolution. That is real evolution. That evolution will go on. But when it comes to this summit, that is God realization. Vāsudevaḥ sarvam iti (BG 7.19). God is the cause of all causes. That is the final realization. Unless one comes to that point, he has not come to the perfection of evolutionary process of the mind and intelligence.

Śyāmasundara: How does our philosophy define mind and intelligence?

Prabhupāda: Mind is instrument. The mind's position is accepting and rejecting. And intellect helps the mind what to reject and what to accept. And that intelligence is of the soul. That ground of intelligence is the soul. First of all bodily concept is gross life, ordinary, like animals, they do not know except the body. Higher than bodily concept of life, the exercise of the mind, mental speculation. And that mental speculation is adjusted by intelligence, and that intelligence belongs to the soul. Therefore soul is the ultimate, and soul is the part and parcel of God. Therefore God is the supreme.

So the mental speculation or the evolution of mental exercise, when it comes to the summit, that is God realization. Vāsudevaḥ sarvam iti, sa mahātmā sudurlabhaḥ (BG 7.19). When one realizes, "God is everything," that mahātmā, that great soul, is very rare. That is the statement in Bhagavad-gītā. Mahātmā means whose mind is great. The mind is great. He's not thinking ordinary things; he's thinking of greater subject matter. They are called mahātmā, broader minded, broad-minded.

Dr. Ware: Do you differentiate, as Jung would do, it's only a matter of attempting to comprehend the differences . . . (indistinct) . . . of things, the difference between thinking and feeling as rational functions?

Prabhupāda: That is the function of the mind—thinking, feeling and willing. Psychological activity.

Dr. Ware: Do you differentiate them separately?

Prabhupāda: Oh, yes.

Dr. Ware: And intuition as well?

Prabhupāda: Saṅkalpa, vikalpa. This is, in Sanskrit it is called saṅkalpa, vikalpa, or accepting and rejecting. That is mind's function. I think something, and again I reject it.

Dr. Ware: Well, you also react, too.